When it comes to being at home in Alaska’s winter landscape, caribou are pretty chill. Alaska has 32 distinct caribou herds in the state, and you have a chance of seeing these hooved critters in almost all of Alaska’s 16 National Wildlife Refuges.

Caribou bodies are incredibly well adapted to survive and thrive year-round in the northern landscapes…while also taking on some of the longest land-based migrations in the world.

Coats for winter and water

Let’s start with the caribou’s coat. There’s a reason northern Indigenous peoples use caribou hides for everything from parkas and socks to camping mattresses: the fur is incredibly insulating and lightweight. A caribou’s dual-layer coat has a wooly under-layer topped by stiff, coarse guard hairs which are hollow and trap air.

This setup means a caribou is essentially clad in long johns, a puffy coat, and a lifejacket at all times, ready for either a chilly sub-zero day or a migratory river crossing through wild Arctic waters.

Shovels on the soles of their hooves

You may know the joys of shoveling snow from a driveway, but shoveling is a continuous survival activity for caribou in winter months. They must move snow to access their food — mainly lichens at this time of year. Luckily, they have the tools for this job, too: shovel-like hooves.

If you hosted a “cervid” family reunion and compared caribou feet side by side with their deer, elk, or moose cousins, you’d see that the caribou’s hooves are proportionally larger, more crescent shaped and more flexible. This design works nicely to scoop away snow like a shovel would, provide more surface area for walking on snow as a snowshoe might, and even function like a paddle for those river swims.

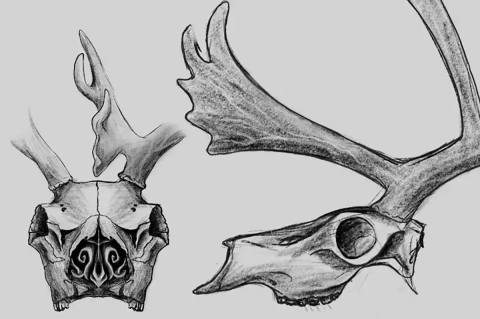

Nose spirals

Did you know the internal workings of a caribou muzzle function kind of like a respirator? Inside a caribou’s nostrils you’ll find “nasoturbinal bones” which spiral around like the inside of a seashell. These bones increase the surface area of the nasal passages and are covered with tissues rich in blood vessels. As a result, air travels a longer path into and out of a caribou’s body. Cold air that is breathed in gets warmed and humidified on its way to the animal’s lungs. As a caribou exhales, the warm air cools down on its way out of the snout, and the nasal passages retain the moisture. This heat exchange design minimizes the energy and moisture caribou lose through respiration on a cold day.

Changing seasons, changing climate

Caribou aren’t always in “jack frost” mode. Their bodies adjust seasonally — hoof pads get spongier in the summer to allow for tundra traction, and they can even change their eye color in the very farthest northern regions that experience total darkness in the winter but tons of light in the summer, like Utqiaġvik at the edge of the Arctic Ocean.

What caribou may have a harder time adjusting to, though, is the changing climate in their home range. The Arctic is warming faster than the rest of the planet, and caribou increasingly face challenges from climate impacts. In the winter, fluctuating temperatures and warmer weather can mean more events where rain falls on snow. This creates a layer of ice that makes it difficult for caribou to get to the lichen they need to survive.

Climate change also drives more active wildfires and changes in the timing and regions of plant growth, snow melt, and insect hatch in the spring and summer — influencing caribou movements. While it’s normal for caribou populations to cycle up and down, climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change complicates how we understand long-term population trends and health for these Arctic animals.

Caribou and People

Caribou are a key part of food security in Alaska — many communities harvest caribou as a primary source of protein. Caribou meat is lean and iron-rich, and caribou fat is an ingredient in many recipes, including versions of the famous akutaq — a special treat of berries mixed with fats, oils, and snow.

Many northern Indigenous peoples have developed close cultural connections to caribou. One example is the Nunamiut people — Iñupiat of the Brooks Range. For generations, the Nunamiut moved around seasonally in accordance with caribou migrations. When a permanent community was established in the 1940s, the Nunamiut selected a mountain pass called Anaktuvuk, the place of caribou droppings, which had good access to the animals. The community connection with caribou continues today.

Words for “caribou” in Indigenous Alaska languages:

- Alutiiq: Tuntuq

- Denaakk’e (Koyukon Athabascan): Bedzeyh

- Gwich’in Athabascan: Vadzaih

- Iñupiaq: Tuttu

- Unangam Tunuu: Itx̂ayax̂/itx̂aygix̂

- Upper Tanana Athabascan: Udzih

- Yup’ik: Tuntuq

Written by Brittany Sweeney, Outreach Specialist for Selawik National Wildlife Refuge. Layout by Lisa Hupp, Alaska Refuges Communications Specialist.

Special thanks to Kyle Joly, wildlife biologist and Arctic Network Caribou Vital Sign Lead. Read more about his program and the Western Arctic Caribou Herd.

In Alaska we are shared stewards of world renowned natural resources and our nation’s last true wild places. Our hope is that each generation has the opportunity to live with, live from, discover and enjoy the wildness of this awe-inspiring land and the people who love and depend on it.