Set in motion at birth, the fate of Pacific salmon is like clockwork: each year a new generation returns from sea to spawn. Then, death.

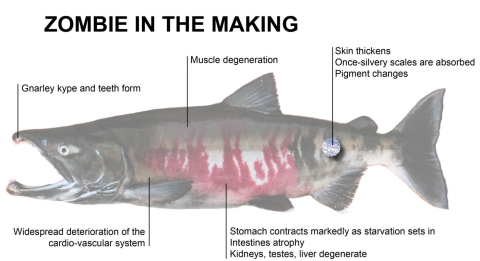

Pacific salmon spawn only once per lifetime. As they make their final journey home, their silver sides blush as pigments that give their flesh its appetizing red hue move to their skin. The fat that mottles their tasty fillets burns up as females become vessels for plump, fatty eggs — for both sexes, fat stored in their muscles and livers is totally used up by the time they reach the spawning grounds. They grind their tails into the gravel, hoping to make deep-enough nests that withstand the scour of ice and spring floods. Males tap into their reserves to grow fearsome teeth and hooked upper jaws that they use against each other.

The changes salmon undergo near the end of their life are profound and system-wide, including the eventual widespread deterioration of internal organs.

The Living Dead

When the frenzy’s all said and done, they’re spent, their fate sealed. It’s a matter of days, a couple weeks at most.

"We found a fish that was most certainly dead — huge chunks missing, badly decayed, an eye gone — but when we picked it up, it was decidedly NOT dead, and took one last opportunity to spawn all over us! Zombie fish!"—@greatlakescisco

Life After Death

Just as they feed the masses when they’re alive, salmon continue to give life long after they’re dead. When the bears are satiated and the fisherfolk have gone home, others partake.

Eyeballs, a sumptuous morsel for beaked scavengers, are often the first to go. Depending where the carcasses lay, they’re fodder for fly larvae and aquatic grazers like caddisflies. In an odd twist of fate, these same insects will feed the new generation of salmon incubating beneath the gravel.

Many carcasses, snagged by fallen trees, stay put or don’t stray far. Others make their way up and over the banks of the rivers and into the woods and meadows, helped along by wildlife and high flows. Here, in perhaps a stroke of genius, the salmon feed trees that provide shade and, when they fall in, habitat for their offspring and snags to keep carcasses in place [more on this: The Quiet Love Affair Between Fish and Trees].

Some slip past, making it back to sea where they will give back some of the marine nutrients they used to fuel their upstream migration.

Salmon Graveyards: a good thing

The rhythmic coming and going of salmon graveyards in streams all over Alaska and the Pacific Northwest is a natural (albeit sometimes slightly ghoulish) phenomenon.

Where salmon runs have declined or been lost, the graveyards stand empty. In some cases, salmon zombies are being returned to rebuild the nutrient deficit and help scientists learn about the important interaction between salmon zombies and their environment.

New episodes of Fish of the Week! every Monday!

We honor, thank, and celebrate the whole community — individuals, Tribes, States, our sister agencies, fish enthusiasts, scientists, and others — who have elevated our understanding and love, as people and professionals, of all the fish. In Alaska we are shared stewards of world-renowned natural resources and our nation’s last true wild places. Our hope is that each generation has the opportunity to live with, live from, discover and enjoy the wildness of this awe-inspiring land and the people who love and depend on it.