The natural world marks the changing of seasons with fascinating rituals. Some animals spend fall feasting to gain as much weight as they can, some seek out secluded places to hunker down before it gets cold, and some pack up the family and travel across the continent for warmer weather.

Whooping cranes opt for the latter. And this fall, more of the majestic “snowbirds” could be flying south than at any time in recent history.

Around 536 wild whoopers just finished summering in the Canadian wilderness, where they nested and raised chicks in Wood Buffalo National Park. Starting in late September, these birds and their young will begin cruising south through the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas and Oklahoma on their 2,450 mile journey to their winter home at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge on the Texas Coast.

Those who live in this flyway might spot the stately birds touching down at local wetlands for food and rest along their journey. To spot a whooper, look for the long-necked, white bird with the red cap, black-tipped wings and little mustache. You won’t miss it – this awe-inspiring creature is “as tall as a man and sings like a cracked calliope.”

Named for its signature “whoop,” which can be heard from at least a mile away, you might hear one of the well-named birds before you see it. But don’t expect a relaxing sound like the coo of a mourning dove or chip of a warbler. Whoopers are no songbird, and it’s been said their call “has never suggested tender emotion, except, possibly, to another whooping crane.”

Regardless of its singing abilities, to hear a whooping crane today is a gift. There was a time when the vanishing bird seemed doomed to extinction.

In 1941, just over 20 of them were left in the world. But even when it looked like they had lost in the contest with man and nature, not everyone lost hope.

“When you sit crouched in a blind and watch an adult whooper stride close by you, his head high and proud, his bearing arrogant and imposing, you feel the presence of a strength and of a stubborn will to survive that is one of the vital intangibles of this entire situation,” said Robert P. Allen in his 1950 book The Whooping Crane. “We have a strong conviction that the whooping crane will keep his part of the bargain and will fight for survival every inch of the way. “

With a little bit of help, whoopers kept their part of the bargain.

Legal Protection

The distribution of the whooping crane was once as widespread as its wingspan. Genetic research indicates up to 10,000 cranes once roamed the continent from the Arctic coast down to central Mexico and from Utah across to the Atlantic coast.

By the late 1800’s, agricultural expansion, wetland degradation and direct take such as shooting and collection had drastically reduced the population.

“As the country expanded into the central flyway, agricultural practices converted wetlands to crops,” said Kevin McAbee, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Whooping Crane Coordinator. “So once all of those wetlands were either drained or converted to fields, it was hard for whooping cranes to find places to stop for food and shelter.”

When they were able to find a suitable spot to stop along their migration route, a different threat awaited them: trigger-happy shooters taking aim on the easy targets. In the early 1900’s, shooting mortality may have exceeded annual reproduction of the species.

In 1918, shooting and collecting whooping cranes and their eggs was slowed by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA), which prohibits take of migratory bird species.

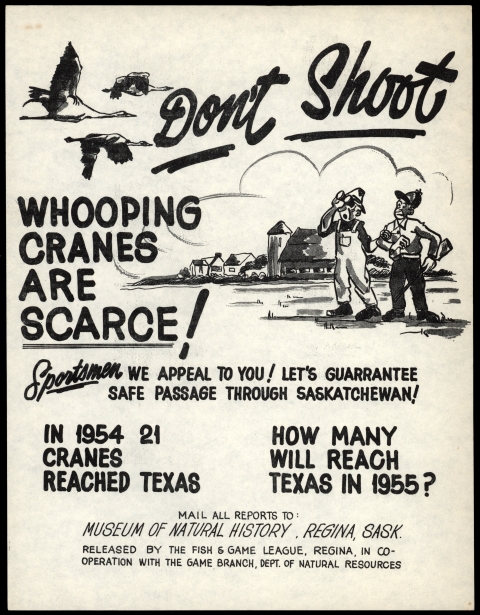

Though the MBTA made it illegal to shoot a whooping crane, the practice didn’t stop entirely. In 1952, the president of the Audubon Society said, “each year it becomes increasingly apparent that illegal hunting is a factor in reducing the numbers of the whooping crane and increasing the threat of their extinction.”

This prompted the Service and other organizations to lead a national public awareness campaign to appeal for safe passage of whoopers along their migration route. They urged hunters not to shoot any large white bird in case they are mistaken for snow geese, white pelicans, American egrets or whistling swans.

By 1973, there were still just under 50 whoopers in the wild. That year, the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973 was signed into law, and whooping cranes were among the first species on the list.

“At its core, the Endangered Species Act is to prevent extinction of our nation's biodiversity,” McAbee said. “And whooping cranes were as close as you can come to extinction.”

Species listed as endangered or threatened under the ESA benefit from conservation measures that include recognition of threats, implementation of recovery actions, and federal protection from harmful practices.

For endangered whooping cranes, passing this protective legislation played a crucial role in raising awareness of the species’ predicament and establishing the authority to implement conservation measures.

“What the ESA really did is it protected the bird’s habitat throughout the country a lot more,” McAbee said. “Now, whooping cranes not only had protections for not being shot and harassed, but they had protections for their habitat.”

Wintering Ground Protection

Long before the ESA became a household word, many Americans were concerned about the whooping crane’s struggle for survival, and the Service acted early to protect their wintering grounds on the Texas coast.

In 1937, Aransas National Wildlife Refuge was established to serve as a breeding ground and sanctuary for migratory birds and other wildlife. At the time, when only 15 whoopers survived in the wild, the refuge became a focal point of the national and worldwide effort to save them from extinction.

“It’s no accident that the area selected for the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge was the major wintering ground for more than 60 percent of the whooping cranes then alive,” Allen wrote. “It may very well have saved the whooping crane.”

Today, the refuge now encompasses more than 115,000 acres of diverse habitat for migratory birds and resident wildlife. Every year Service biologists conduct aerial surveys to count wintering whooping cranes, in addition to conducting on-the-ground habitat restoration efforts and research aimed at conserving the endangered birds.

While on their wintering grounds, refuge visitors can see the iconic birds on a commercial boat tour or from the refuge’s trails and observation tower. If they’re lucky, visitors might even get to see the birds perform one of their signature dance routines, which Austin American Statesman columnist Nat Henderson once described as an avian square dance.

“They whoop and kick up their heels like cowboys doing the Cotton-Eyed Joe,” Henderson wrote. “I suppose they learned that while wintering in Texas.”

Summer Nest Protection

Though people had long known about their winter home in Texas, for many years the location of the whooper’s “secret summer rendezvous” in the Arctic was a mystery. Some believed the species was doomed unless their nesting grounds could also be found and protected, which drove years-long efforts by scouts trying to spot the elusive birds.

In 1947, the Service tracked the birds from Texas all the way to Canada in an airplane before losing the trail in a narrow valley where the Mackenzie River empties itself into the Arctic ocean. But it wasn’t until 1954 that their true nesting location was found. That year, a breakthrough was made when foresters rushing in by helicopter to control a fire in a remote section of Northern Canada’s Wood Buffalo National Park spotted the white birds on the landscape.

Though the park had been established in 1922 to protect imperiled wood bison, researchers believe the early establishment of the park contributed to the survival of the endangered cranes as well.

Today, the whooping crane nesting area in the remote park is protected as a Ramsar site, or Wetland of International Significance, and Wood Buffalo National Park and the Canadian Wildlife Service conduct monitoring surveys annually.

Captive Breeding

In 1950, the New York Times reported they had received a bulletin that “shook the bird world.” Watchers perched on an observation post at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge spotted something exciting through a telescope – a reddish-brown chick had been born from two whoopers being held at the refuge.

Rusty, as the baby would be named, was the first whooping crane ever hatched in captivity. It was an important milestone – the last time a nest had been observed by humans in the U.S. was in 1890.

Though Rusty unfortunately didn’t survive very long, his mother Josephine went on to have many more chicks, including the first ever whooper born in a zoo in 1956.

These headline-making baby announcements were an exciting start to a successful captive breeding program that continues today. Because the wild, self-sustaining population could be heavily impacted by a single catastrophic event, the whooping crane International Recovery Plan highlights captive breeding as one of the key recovery strategies that can help protect the bird from extinction and bolster its numbers so that one day it could be taken off the ESA list.

Today, 130 whooping cranes are living in captivity at 20 locations across the U.S. and Canada. These facilities hold breeder pairs, produce birds required for reintroductions and do extensive research to improve the production of captive flocks.

“It’s amazing how much effort goes into rearing chicks at a facility to an age old enough to release it into the wild and how much cooperation it takes between these facilities,” McAbee said. “These facilities are coordinating on a continuous basis to make sure that mating pairs are getting along and they're successfully breeding.”

Reintroductions

In 1975, New Mexico received a few “superstar” visitors. Four young whooping cranes, the first of their species to visit the state since the 1850’s, had arrived with thousands of sandhill cranes.

Earlier that year, as part of an experimental plan, eggs taken from whooping crane nests in Canada were flown to Idaho and transferred to nests of sandhill cranes. The hope was that the sandhills would raise the young whoopers as their own, leading them into migration and beginning the establishment of a second population in the wild.

The whoopers bonded with their foster parents, but unfortunately they also used the sandhills as models for their future mates and never ended up reproducing with their own kind.

Despite this setback, the whooping crane community held out hope that additional populations could still be established in the U.S.

In the early 2000’s, partners used lessons learned from earlier reintroduction attempts and established a new Eastern Migratory Population in the U.S. This population is made up of a mix of captive-reared and wild-hatched cranes that summer in Wisconsin and winter in Florida.

In 2011, another population of whooping cranes was introduced in Louisiana. This non-migratory population is made up of captive-reared cranes that hang out in marshes and rice fields in Louisiana and occasionally in Texas.

Today, more than 151 whooping cranes are living in these two reintroduced populations, also known as Nonessential Experimental Populations (NEP). Though both are reproducing, they need some assistance from humans to survive.

“The reintroduced populations do reproduce in the wild, but not at levels to support a population,” McAbee said. “They both rely on captive-reared individuals to support their existence.”

Despite this challenge, they have met some incredible milestones over the last 20 years: learning a migration route in the eastern U.S., establishing summer and winter home ranges, and finding mates, nesting, and hatching and raising chicks in the wild.

A Bright Future

When the ESA was passed into law in 1973, outdoor writer Don Oakley noted the whooping crane had become “the living symbol of our belated realization of how much of our natural heritage we have lost, and how much we are in danger of losing. If the whooping crane can make it, maybe there’s hope for a lot of other things.”

50 years later, it’s safe to say the whooping crane might just be making it.

The annual population growth of whooping cranes has averaged an impressive 4.5 percent per year.

Nearly 800 are now living in the U.S., well-protected from natural disasters by being spread out among dozens of facilities and wild locations across the country.

Wetlands have become a focus for landscape restoration, with many organizations working to restore lost and impaired wetlands across the country.

“In my parents’ lifetime we have brought a species back from the edge of extinction to now flourishing and growing in such a way that we have a population of almost 550 wild birds that migrate, reproduce and overwinter across two countries,” McAbee said. “That's a monumental success.”

Undoubtedly, the public and private coordination across state and national boundaries has been an essential factor in that success.

“So many people care about this large, beautiful, iconic bird,” McAbee said. “Multiple nations and states and tribes are managing for this species, along with the help of zoos, nonprofits, private landowners, bird watchers and the public. The Endangered Species Act has given us the policy framework to bring all these people together with a common goal, and without that legislation, our partnership wouldn’t be as cohesive as it is.”