Since the Endangered Species Act was signed into law in 1973, wildlife biologists have been hard at work finding ways to recover imperiled species and restore the ecosystems on which they depend. Unfortunately, sometimes ecosystems fail, and conservation professionals need to spring into action to keep imperiled species alive.

Over the summer of 2023, New Mexico’s typical monsoon rains failed to arrive, threatening the existence of native aquatic species that have managed to eke out a niche in this desert southwest state.

“The monsoons didn’t come, then we had parts of our creeks that dried out completely and water just stopped flowing,” said Carl Jacobsen, who’s a wildlife biologist at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge near Roswell. “According to our records and locals we talked to, that has never happened. A lot of springsnails were dying, at least 100,000, possibly millions.”

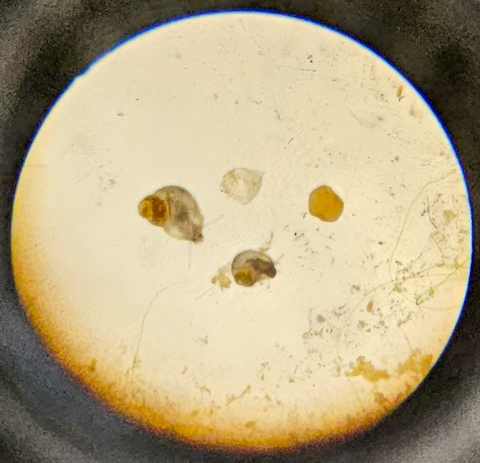

Springsnails are tiny aquatic mollusks that inhabit spring systems and are often indicative of the overall health of their unique ecosystems. The Bitter Lake Refuge is home to two imperiled species: the Koster’s and Roswell springsnail. They measure in at around 1.5 millimeters in length. A microscope is needed to tell the two species apart. Both exist exclusively on the refuge. Because they are so small, the genetics from one section of the spring habitat can vary greatly from another. With the effects of climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change causing hotter and dryer conditions, farms in the area required more water resources to keep crops from failing, which contributed to the drop in spring flows.

With that section of the creek quickly drying out, the biologists carefully collected some springsnails, taking care to minimize harm to the ecosystem. “We went in and harvested 1,500 snails. That sounds like a lot of snails, but we got all we needed from just a couple of scoops from the creek,” added Jacobsen. They’re so small and delicate that to count them, biologists and technicians must lay the collected substrate on a white tray and separate the snails count them with a fine a paintbrush. It takes a close look to differentiate snails from the grains of sand they’re mixed in with.

Because the refuge lacks aquarium facilities, the biologists brought the springsnails to the Southwestern Native Aquatic Resources and Recovery Center in Dexter, New Mexico. Like a reverse Noah’s Ark, the hatchery in Dexter served as a refugia from a drought rather than a flood.

“We spent many hours collecting snails as they climbed to feed on algae growing on the walls of the enclosure at the Dexter hatchery,” elaborated Jacobsen. The biologists and technicians carefully sorted through sand and algae in the refugia and used microscopes to ensure the health the snails before returning them to the collection location.

The collected specimens enjoyed a very high survival rate during their little vacation, and they even thrived, as thousands of juvenile springsnails were born in the enclosure. For this small population, a crisis was avoided.

Thankfully, toward the beginning of autumn, New Mexico’s residents and wildlife did eventually enjoy a tardy monsoon season. With water levels back to normal and summer heat giving way to fall tepidity, the springsnails were repatriated back to Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge.

Dec. 28, 2023, marks the 50th anniversary of the Endangered Species Act. As demonstrated at Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge, endangered species recovery is complex and difficult work, often requiring substantial time and resources. The visionary, innovative, and determined actions taken by Service team members and partners such as the Bureau of Land Management, contributes to the success of the Endangered Species Act.