Hatcheries Grow Freshwater Mussels

National fish hatcheries are helping protect aquatic resources by raising and stocking freshwater mussels and their host fish. Visit a few of our mussel propagation programs.

Harrison Lake National Fish Hatchery

White Sulphur Springs National Fish Hatchery

Wolf Creek National Fish Hatchery

Beneath the surface of the water, embedded in river bottoms, hidden in estuaries, and mistaken for rocks, lurk the invisible engineers of our aquatic ecosystems. Throughout our waterways, from urban rivers to the country streams, countless freshwater mussels are cleaning the water, taking out the trash, and stabilizing the entire aquatic community. But that’s not all! These miraculous bivalves are also locked in a dramatic and ancient love affair with their better-known aquatic neighbors. The fish.

And the Fish Makes Three!

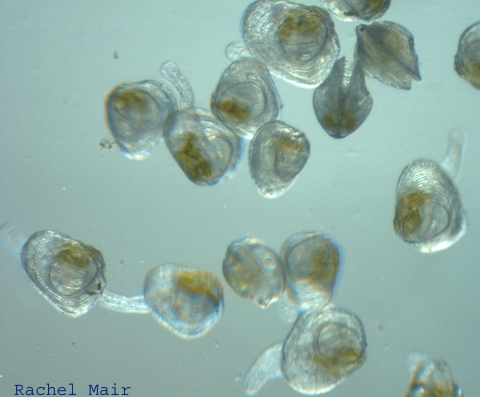

Successful mussel reproduction requires more than just a male and female mussel. They need a third partner to complete their cycle. When male mussels release sperm, nearby female mussels will filter it from the water. Female mussels then “brood” their fertilized eggs, or larvae, in specialized brood chambers for several months. Once the larvae are ready to enter their next stage of life, the magic really begins! To complete their metamorphosis from larvae to juvenile mussels, they need a little help from an unsuspecting fishy host.

In order to attract the right species of fish, female mussels put on a show, and the performances are impeccable! Sometimes, like an improvisational dancer she undulates and waves in the water, disguising herself as a small minnow, an aquatic insect, or perhaps a crayfish to entice and captivate nearby predators. When the hungry fish approaches, the female mussel expels her larvae in an explosive burst at the fish. Other times female mussels play the part of expert angler, casting lures and crafting nets to catch her prey. The fish strike at the floating lures or swim into the floating nets of larvae.

The mussel larvae, called glochidia, typically clamp on to the gills of the fish, but may also attach to tails or fins, where they will complete their next transformation. For several weeks the mussel larvae harmlessly ride along on the fish as the fish swims around doing fish things. Eventually their metamorphosis is complete and they drop to the river bottom as a mussel.

Without this unique adaptation, mussel beds would naturally migrate downstream with the flow of the river. By hitching a ride on the gills, fins, or tails of a fish, mussels evolved a way to actively move future generations of mussels upstream or just remain in place in the river. Fish benefit from the relationship as well. Some fish lay their eggs inside the shells and gill cavity of living freshwater mussels, and fish may also gain some immunity to stress after serving as a host to freshwater mussel larvae.

Guardians of the Waterways

North America has close to 300 species of mussels, the highest diversity found anywhere in the world! But over 70% of all species of freshwater mussels are in decline, 7% are extinct, 21% are listed as endangered, and another 40% are listed as threatened. The loss of any of these species will definitely have consequences on how the aquatic ecosystem functions. Freshwater mussels are one of nature’s greatest natural filtration systems. Not only do they stabilize aquatic ecosystems, they also continually protect and improve water quality. “A single freshwater mussel can filter 5 to 10 gallons of water per day, 365 days a year,” said Dr. Danielle Kreeger, Science Director for the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary.

Freshwater mussels are in decline across the country, and it’s putting the health of our rivers and lakes in jeopardy.

Although mussels have amazing pumping and engineering skills, they have their limits. Threats to freshwater mussels include modification of rivers and streams, obstacles that prevent their host fish from migrating, excess sedimentation, contamination from legacy industrial and agricultural practices, and the spread of invasive species like zebra mussels.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is working with state, tribal, and other federal partners to restore freshwater mussels and the ecosystem services they provide. We are propagating and stocking mussels back into historic habitats, and working with landowners and communities to repair degraded habitat and restore aquatic connectivity for fish.

Learn more about freshwater mussel conservation.

Search for threatened and endangered mussels in your state.

https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp0/reports/ad-hoc-species-report-inputRead about mussel conservation on the San Saba River in Texas

https://legacy-www.fws.doi.net/southwest/stories/2020/san_saba_mussels.htmlDIY mussel conservation at Richard Cronin Aquatic Resource Center.

https://medium.com/usfishandwildlifeservicenortheast/partners-working-to-conserve-freshwater-mussels-find-strength-in-numbers-66a5993722bf

By Catherine M. Gatenby, Ph.D., Senior Fisheries Biologist/Communications with the Lower Great Lakes Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office, and Holly Richards, a Fish Enthusiast with the Branch of Communications and Partnerships, Fish and Aquatic Conservation.