On Prince of Wales Island, they call it "herring egg weather"—a snow flurry may usher in blue skies that quickly cloud up and cast down rain or snow…all within minutes. Boats are readied and hemlock trees and branches cut. Yaaw (Tlingít for Pacific Herring) are staging to spawn. Marina Anderson, who grew up there, shares her perspective:

“I can remember being in elementary school hearing the clunky boots walking down the hallway and looking out the window at the playground and seeing the different weather coming in all at once. The combination of those wetter weather patterns, plus hearing those…meant my mom was coming into my classroom to take me out of school for the next 10 days. And there were no questions from the teachers…They just knew…”

Listen to the full conversation here at FWS.gov, on Apple podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Wildlife are getting ready too—here and there, wherever the herring spawn.

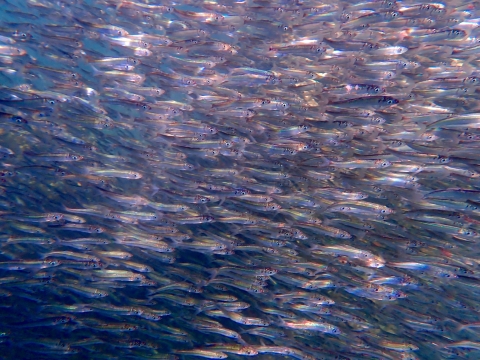

Many will come to the coastline and beaches to gorge on the massive schools of fish and their eggs in the shallow waters. Eagles will gather in huge numbers in the trees near the shore. Seals and sea lions will dive in and out of the spawning school of herring, happily filling up on a yearly serving of compact, oily-fleshed fish. A herring buffet whose spawning activity is also important to the animals of the forest. Even wolves and black bears will come to the shore to feast on the calorie-dense, fat-rich protein source.

Spring Arrives

The arrival of thousands of tons of the shining silver fish to the coastal bays and estuaries of Alaska, British Columbia, and Washington in March is a sure sign of spring. The herring arrive to perform their ancient spawning ritual and welcome another generation to their brood. Each female lays up to 20,000 sticky eggs (roe) while males do their part and turn the coastline waters a milky turquoise with their milt during the mass spawning event.

The adhesive eggs stick to the vegetation in the shallow coastal waters—including kelp and the hemlocks trees that have been sunk near shore.

Fish Eggs and Traditional Ways

Pacific Herring are an important beginning to the year among the Native peoples all over these coastal areas. The eggs and meat they provide bring an early year subsistence food source. In Bristol Bay, Yup’ik people harvest the herring on bubble kelp strands as well. It is frozen and enjoyed year round and once thawed it pairs well with seal oil and soy sauce. It is called Melucaq (Mel-ooh-chew-wakk) in Yugtun (Yup’ik). The Tlingít and Haida peoples of Southeast Alaska use hemlock branches in the water to create easily harvestable surfaces for the fish to lay their eggs. When the branches are pulled, the eggs are attached.

“Herring eggs pop a lot in your mouth. It's not like a movie theater snack by any means. They're really loud. It's kind of like when you're the only person eating chips. And you're really aware that you're the only person eating chips, you're very aware that you're the only person eating herring eggs in the room.”

There are many ways to preserve the eggs: freezing in saltwater, packing salt around the eggs, boiling, frying, and pickling. The roe are often accompanied by seal or Hooligan oil, soy sauce, butter, mayonnaise, vinegar, or salt and pepper.

“The flavor, I would compare it to…the ocean…They just taste like we're supposed to be eating them.”

Any way the roe is prepared, it is a true delicacy and an important subsistence food for the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific coast. With Archaeological evidence proving Pacific Herring have been an important First Food for millennia: their bones have appeared in almost all 171 archeological sites tested in Alaska, British Columbia, and Washington with samples dating back over 10,000 years before present according to this Archeological study.

Concentric Circles of Life

Pacific Herring hold a place of both predator and prey in the cycle of life. Born along the coast where their parents first caused commotion and a fleeting flurry of activity, the newborn herring will stay there for their first weeks. At this larval stage of life, they’ll feed on the smallest of phytoplankton due to being less than half an inch long themselves. At 2-3 months old, juvenile herring begin to form schools. With increasing size, they become food for larger animals including other fish, birds, and marine mammals.

Pacific Herring have a great effect on their environment due to their place in the food chain. They are a keystone to the proper balance the environment. They feed the salmon, halibut, lingcod, and rockfish. From egg to larvae, juvenile, fingerling, and adult, each stage of life highlights the Pacific Herring’s important place in the food chain. Their health is tied to the health of many others—the fish, the birds, marine mammals and people.

Looking Towards the Future

With their bluish-green upper bodies and glistening silver sides, Pacific Herring have an inherent beauty (their shimmery scales can leave you looking lovely as a mermaid if you happen to handle one).

They may be small in your hand, and seem abundant, but they’re also fragile to the whims of changing sea conditions, climate, and fisheries wherever they’re found—from Baja California north to Alaska and into the Bering Sea, from Russia down through Korea, China and into the waters of Japan.

Pacific Herring numbers fluctuate year to year and place to place. Where their numbers are receding, there is worry.

“When we have a year, where it's hard to get those eggs, you see it reflected socially within our communities.”

For thousands of years, Indigenous peoples have been looking at all of the parts of the ecosystem as a whole, not separate.

“What I really wish for the next generations is that the knowledge we hold today, when it comes to harvesting and taking care of these herring—I hope that's passed down. I also hope the next generation is at the table when it comes to management and decision making with the hearing and with the herring eggs…If the herring go, everything starts to fall apart.”

><> ><> ><> ><> ><> ><> ><> ><> ><> ><> ><> ><>

Catch new Fish of the Week! episodes every Monday!

We honor, thank, and celebrate the whole community—individuals, Tribes, the State of Alaska, sister agencies, fish enthusiasts, scientists, and others—who have elevated our understanding and love, as people and professionals, of all the fish. In Alaska we are shared stewards of world renowned natural resources and our nation’s last true wild places. Our hope is that each generation has the opportunity to live with, live from, discover and enjoy the wildness of this awe-inspiring land and the people who love and depend on it.