The Fish of Ten Thousand Casts

Nestled between New York and Canada, the St. Lawrence River is a beautiful waterway full of amazing freshwater fish species. A variety of sportfish, including bass, northern pike, and walleye thrive here, attracting anglers from across the country to engage with nature, and experience what this region has to offer.

But one fish conceals itself from many, “the fish of ten thousand casts.”

The Muskellunge.

Muskellunge (or musky) captivate anglers with their power, size, and difficulty of being caught due to their elusive nature. These North American natives glisten in the water, holding the title of the largest freshwater sportfish in New York State. Musky are found in lakes and rivers across the state, but the St. Lawrence River is one of the most acclaimed. Musky are a piscivorous species, consuming a variety of other fish. Over the last two decades, biologists have observed a decline in musky populations within the St. Lawrence River. The State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY ESF) partnered with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), to develop a plan with specific goals to protect these important sportfish and restore their populations.

Dr. John Farrell, Professor, and Aquatic and Fisheries Science Director at the Thousand Islands Biological Station (TIBS), and his team of faculty and students documented musky populations declining. The recent decline is a result of the introduction of round goby and Viral Hemorrhagic Septicemia Virus (VHSV), in addition to ongoing habitat loss. Through funding provided by the Fish Enhancement, Mitigation and Research Fund (FEMRF) and NYSDEC, TIBS has begun a recovery program monitoring and propagating musky for release in the St. Lawrence River. This experimental stocking program has been underway since 2017 and is part of an adaptive management strategy, developed by TIBS, called the Fish Habitat Conservation Strategy (FHCS). Some of the main goals through this plan are to continue to research, monitor, and protect this critical species through habitat protection and propagation (egg collection, fertilization, and release) in areas impacted by invasive species invasive species

An invasive species is any plant or animal that has spread or been introduced into a new area where they are, or could, cause harm to the environment, economy, or human, animal, or plant health. Their unwelcome presence can destroy ecosystems and cost millions of dollars.

Learn more about invasive species and pathogens. To learn more about FEMRF: https://www.fws.gov/project/fish-enhancement-mitigation-and-restoration…;

The fight for musky pushes on. There are known ecological factors at play that continue to threaten musky populations in the St. Lawrence River. Dr. Farrell and his team at TIBS are continuing to study these issues to execute positive change for this species and others. Without the ongoing support from the river community, including anglers, and organizations like TIBS, non-governmental organizations such as Save The River, and federal and state partners, the St. Lawrence River musky population would be at risk of continued decline.

Changes in musky habitat, including loss of spawning areas, has been directly impacting the spawning success for St. Lawrence River musky for decades. Spawning habitats for musky are often shallow areas of lakes and rivers, often along shorelines. These diverse areas draw people, who introduce man-made structures to shorelines like seawalls and docks. This process is called shoreline hardening. Meant to maintain and reduce eroding shorelines, this process can be detrimental to species like musky because it eliminates vegetation used as their preferred spawning sites. It is important to note that climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change also plays a role in this issue, with additional impacts from increased water temperatures and elevated water levels that increase shoreline erosion. Land conservation efforts by the Thousand Islands Land Trust is helping the musky population by protecting critical spawning and nursery habitat through conservation easements and creating forever wild preserves.

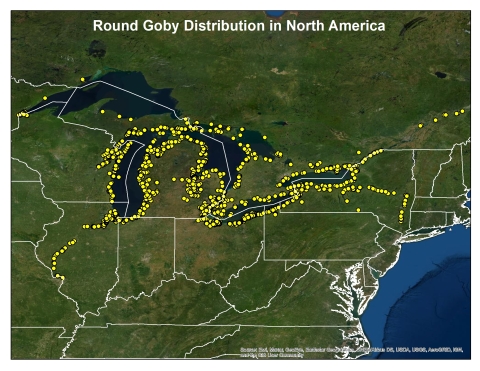

One of the most recently documented threats to musky are the impacts of invasive species, specifically the round goby. This invasive fish originated from the Black Sea and was first documented in the Great Lakes, along the St. Clair River, in 1993, reaching New York in 1998. They entered the United States in freighter ballasts, which are tanks on large ships that take in water to help with balance and stability.

et al. (2019).

Round gobies are known to eat invertebrates and fish eggs, including musky eggs. Round gobies reproduce around every 20 days during their spawning season, which occurs from April to September. Although many fish species eat round gobies, predation does not limit their populations because they reproduce at such a rapid rate. They are prevalent in many New York watersheds, including the St. Lawrence River, and efforts are currently underway to prevent them from reaching Lake Champlain.

TIBS is also conducting research on and monitoring Viral Hemorrhagic Septicemia Virus (VHSV), a fish pathogen that is easily spread between fish species. It was first identified in the St. Lawrence River in 2006 after fish die-offs linked to the pathogen. Some fish species are more susceptible to infection and sickness, including musky, and it is difficult to know when fish have been infected. VHSV also mutates, which adds to the difficulty of tracking the virus and the fish it is infecting. Unfortunately, the invasive round goby is a “perfect host” for this disease. With the presence of round goby in musky habitat along shorelines, they are acting as a reservoir for the virus, spreading it to other species they come in close contact with. Studies are actively being done on VHSV in musky populations, but mutations are outpacing results, so the future remains unclear. You can help stop the spread of VHSV by cleaning your boat and its bilge and refraining from transporting fish between different bodies of water. To learn more about VHSV and what more you can do to reduce spreading the virus: https://www.dec.ny.gov/animals/25328.html

So, with all these problems directly impacting musky populations, it is critical to understand what the propagation and restoration process looks like. Musky are known to return to spawn at the same embayments from one year to the next, referred to as reproductive homing. Musky spawn naturally in the wild, with males and females swimming side by side looking for adequate spawning habitat. In the St. Lawrence River, musky spawn in embayments, that consist of shallow, vegetated areas. During spawning, musky eggs and sperm (in fish called milt) are released simultaneously. The fertilized eggs then sink to the bottom until hatching occurs, which is 8 to 14 days. Once the eggs hatch, the musky fry feed on zooplankton. As the musky grow, and switch to foraging fish, they enter the fingerling stage and continue to grow rapidly, reaching 30-34 inches in length five years and soon after they will begin to spawn at age 6-8 for females.

Scientists are hopeful that with propagation, experimental stocking, and natural resistance to the virus the population will bounce back. With populations continuing to decline due to VHSV many of these good quality spawning habitats will go unused. One of the goals of this experimental stocking program is to jumpstart spawning activity in these historically productive spawning habitats. Researchers hope that by temporarily stocking muskies in these good quality spawning and nursery habitats that these fish will return to these embayments once they reach reproductive maturity and increase musky populations in the St. Lawrence River.

Check out this video of a pair of musky during spawning season in the St. Lawrence River: https://youtu.be/6jCbHIuxRUU

Each spring, the TIBS team and the USFWS set trap nets in embayments along the St. Lawrence River, targeting adult musky for collection of gametes needed for the experimental rearing and stocking program. Nets are set along shorelines and as fish swim along shore, they are guided into a funnel that leads them into a holding net. Nets are checked daily; any musky caught are kept in a separate holding pen while all other fish are released.

Once a pair of musky is caught the teams converge and prepare for egg and milt collection. On egg take day, the TIBS team meets the FEMRF team with materials and the process begins.

Here is the breakdown of events at the egg and milt collection, to rearing, and stocking into the St. Lawrence River:

Musky are brought from the holding pen with a nylon bag to safely transport them into a temporary holding tank located on shore.

A length, girth, scale sample and genetic sample are taken from both males and females, along with an additional ovarian sample from the females.

Males are lifted out of the water quickly and milt is collected from the males using a syringe. This ensures none is wasted, the area stays dry, and milt from different males are kept separate. Females are lifted out of the water quickly, and eggs are collected in a separate bowl for each female.

Milt from males is added and carefully mixed into eggs.

Then, the bowls of eggs and milt are carefully stirred around with river water. This activates the fertilization process. Then they are rinsed with river water.

All the separate crosses (male and female mixes) are placed in their own cooler with river water for transportation.

Once all the crosses are complete and properly stowed, the musky are safely tagged with Passive Integrated Transponders, or PIT tags, and released back at the sites where they were caught.

All the fertilized eggs are taken to TIBS after they are treated with iodine and transitioned to their temporary summer home. This iodine bath removes viruses and bacteria that could be on the surface of the egg. The fertilized and unfertilized eggs are sorted and monitored as they develop in hatching jars.

Once the fertilized eggs hatch, which takes about two weeks, they are placed in a raceway to continue to grow for about 10 days and are monitored and inventoried. Once they reach an inch long, the first round of musky are ready to be released back into the river as advanced fry mid-summer.

Advanced fry are too small to receive a PIT tag. Instead, they are marked with OTC (oxytetracycline) which is a liquid that stain the young muskies boney structures. This will allow researchers to tell that they were raised at TIBS. Under a microscope, biologists would be able see this stain on the muskies ear bone, called an otolith.

The second and final round of muskellunge that are released are called fall fingerlings. They are released when they grow to around 10 inches. They are tagged with the PIT tags, due to their larger size. The release date for the fall fingerlings is around September or October.

The partnership between TIBS, the NYSDEC, and the USFWS will continue through this experimental stocking program. The hope is that musky populations will benefit from this collaborative effort.

There has also been a new development on how local anglers can help. Again, funding from FEMRF has allowed TIBS to initiate a Musky Angler Program. This program is funding multiple tagging kits for Canadian and American anglers to assist in the ongoing research and monitoring of musky as they fish the St. Lawrence River. The anglers participating in this program will have successfully completed training with TIBS, USFWS, and NYSDEC this summer to learn how to properly scan for PIT tags and collect basic biological data from musky if caught. This new program will not only help these organizations monitor and manage musky populations in the St. Lawrence River, but also encourage citizen science and musky awareness.

In the Great Lakes region, there is a 54 inch long minimum size requirement for anglers to keep musky. This change was made to protect the large fish, specifically the large spawning females so they can continue to support the population. Anglers should practice catch and release with this species, as we understand the beauty of this fish and want to ensure its presence for decades to come (visit the Save the River website for more information on musky programs). If you happen to catch a musky on the St. Lawrence River, handle them with the utmost care, leave them in the water when unhooking them, and respect them to ensure their unharmed release. These processes have directly benefited the population of species in the St. Lawrence River.

Keeping ecosystems protected allows them to prosper, and this resilience will protect them from future ecological threats like diseases, invasive species, and other disturbances. It is all about education and awareness. These organizations are doing their part to help sustain a critical sportfish population in one of most crucial waterways in New York State. Did we “hook” you on saving musky? To learn more about the program and musky management, visit the Thousand Islands Biological Station website.

For more information on the USFWS New York Field Office: New York Ecological Services Field Office | U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (fws.gov)

Published by Lauren Kelly. Lauren is the 2022 Outreach Coordinator for the USFWS New York and Long Island Field Offices. She uses her passions of wildlife photography and storytelling to share important wildlife stories to the scientists and the public.