CoP19 Spotlight on Species

The United States is a proponent or co-proponent of proposals to help further protect a number of species through CITES. Learn more about some of these species and the conservation threats they face in the below profiles. Please also note that the United States is developing positions on a variety of proposals that will be discussed for many other additional species and policies at CoP19.

Native Freshwater Turtles

Of note among the proposals at CoP19 are the large number of U.S. native reptile species under consideration for inclusion in one of the CITES Appendices, including 36 species of U.S. native freshwater turtles. Turtles face unique challenges and are among the most imperiled vertebrates on earth, but CITES can help them persist by providing oversight for trade — a growing stressor on many species. Learn more about our turtle proposals.

Desert horned lizard (Phrynosoma platyrhinos)

Description

The desert horned lizard is a reptile that depends on heat from its environment to raise its body temperature for activity, feeding, digestion, and reproduction. Individuals are known to hibernate during colder months. The species is considered an ant specialist, though its diet includes a variety of slow-moving insects and occasionally spiders and plant material. Individuals move from ant colony to ant colony in search of food. In areas of soft sand, they shake themselves, throwing sand over their bodies and leaving only their head exposed, and wait for prey. Desert horned lizards represent an important link in the foodchain as they are both predators and prey in their terrestrial environment.

Habitat

The desert horned lizard is native to the United States and Mexico, inhabiting desert shrublands and the lower reaches of interior chaparral and Great Basin conifer woodlands.

Threats

This species is subject to international commercial trade, primarily as pets. From 2013 to 2017, 317 shipments totalling 8,568 individuals were declared for import to or export from the United States. Most (99 percent) originated in the United States, and the majority (96 percent) were taken from the wild. This species is difficult to keep alive in captivity due to its specialized dietary needs. Trade is currently at levels that have not been vetted for sustainability, and there is not enough knowledge about population sizes at rangewide or local levels. Regulations at the state level for the species within the United States are varied. The United States is proposing the inclusion of this species in CITES Appendix II.

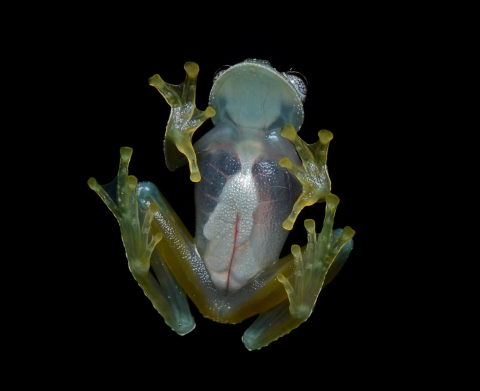

Glass frogs (Family Centrolenidae)

Description

Glass frogs are charismatic species with large eyes and transparent skin. They are traded internationally, mainly as exotic pets. This is likely because of their unique transparent skin underneath the body through which their internal organs can be seen. They are small to medium-sized amphibians. Their colors typically range from green to brown, with transparent skin on the belly, creating a see-through window where parts of the internal organs and bones are visible. Most species have yellow or silvery eyes, fine black speckling or reticulation, and minimal patterning on the dorsal surface of the body, often involving highly variable amounts of spots and speckles.

These frogs are critical species in riverine food webs, where they play an essential role in food chain dynamics and serve as indicators of ecosystem health. They also form part of the functional ecological groups that keep insect populations under control, including those that can transmit diseases to humans, such as malaria, zika, and dengue.

Habitat

Glass frogs require habitats with undisturbed forests that contain permanent bodies of running water such as streams and waterfalls. Like all amphibians, they are highly vulnerable to pollution. Glass frogs are distributed throughout tropical Central and South America. They range from southern Mexico south into northern Argentina, and across the Andes from Venezuela to Bolivia. Despite this expansive range, many species have highly fragmented distributions. The greatest species diversity is concentrated in the Andes of Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru.

Threats

Currently, one of the main threats is the existing trade. Demand for these animals by the international pet trade has multiplied, with an increase in the number of glass frogs for sale on websites, mainly in Europe. The number of specimens in the pet trade in the U.S. has increased exponentially, going from 13 live individuals in 2016 to 5,744 individuals in 2021. Most glass frogs are sold in Europe, the United States, and Canada. Due to the multitude of environmental and pathogenic pressures that are already causing the decline of many of these species, the increase in demand, and the difficulty of distinguishing between different species of glass frogs, any unregulated trade is likely to be detrimental to wild populations of the entire family. Together with Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, Cote d’lvoire, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Gabon, Guinea, Niger, Panama, Peru, and Togo, the United States co-proposes the inclusion of all glass frogs in CITES Appendix II.

Aleutian Cackling Goose (Branta canadensis leucopareia)

Description

The Aleutian cackling goose (Branta hutchinsii leucopareia) is significantly smaller than the Canada goose (Branta canadensis) and has a shorter bill. They both have a black head and neck, brown wings and back, and a white cheek patch. Most Aleutian cackling geese also have a white “necklace” or ring at the base of their neck.

Habitat

The Aleutian cackling goose is a migratory sub-species that spends summers on treeless islands and relies on agricultural lands during the winter. It is known to disperse plant seeds and its foraging can help maintain the diversity of grassland communities and promote the co-existence of plants. Historically, the Aleutian cackling goose occupied breeding grounds on dozens of islands across the North Pacific during the summer and migrated south for the winter to Japan and the west coast of North America, including Canada, Mexico, and the United States. Today, most Aleutian cackling goose populations inhabit the United States, and a small population can be found in Russia and Japan, with approximately 1,700 birds estimated to live in the Kuril Islands during the summer and in Japan during the winter. In Mexico, the subspecies has occasionally been recorded in the California peninsula (Baja California and Baja California Sur) and the Colorado River delta.

Threats

The booming feather trade in the 19th and 20th centuries and overexploitation drove this species toward the brink of extinction. The Aleutian cackling goose also suffered severe declines after non-native foxes were released on most of their breeding islands to propagate the fur trade. The foxes consumed their eggs, goslings, and even molting adults. In 1973, the Aleutian cackling goose was one of the first species protected by the Endangered Species Act in the United States, and in 1975, Branta hutchinsii leucopareia were included in Appendix I of CITES (listed as Branta canadensis leucopareia). A multitude of recovery efforts, many led by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and its partners, helped the Alaskan population significantly increase in recent decades. For CoP19, the United States submitted a proposal to change its listing from Appendix I to Appendix II.

Timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus)

Description

The timber rattlesnake is one of 15 rattlesnake species in North America and is morphologically distinguishable from others by the dark W-shaped bands or zig-zag chevron patterns across its dorsal scales. Northern populations of timber rattlesnake are generally darker compared to lighter-colored southern “canebrake” populations. “Yellow” color morphs are found range-wide while “black” morphs are typically only found in northern regions. Rattlesnakes play a prominent role in maintaining primary ecological structure, function, and pest control.

Habitat

This species is endemic to North America. Historically, timber rattlesnakes were found in 33 midwestern, southern, and northeastern states in the United States and in the Canadian province of Ontario along the Niagara Escarpment. This species is threatened with extinction in 47 percent of its southern range and is extirpated in two States in the United States as well as Canada in its northern range. Past reports exist of the species occurring in extreme southern Quebec along the United States border. In 2001, the species was considered extirpated in Canada after it had not been seen since 1941. Maine and Rhode Island also declared the timber rattlesnake extirpated.

Threats

The timber rattlesnake is threatened by habitat fragmentation, as it requires undisturbed and connected habitats around its dens during the spring, summer, and fall to maintain viable populations. It is also threatened illegal trade and unsustainable use. Timber rattlesnakes have a heavy presence in the live pet trade, reptile skin trade, venom trade, and are sold as “novelty” items (e.g., life-like specimen mount, tail rattle jewelry). The species is declining, with severe losses across its range in the United States and Canada. Including the species in Appendix II would complement state and other domestic measures and regulate any trade in this species nationally. It will ensure speciments entering international trade are acquired sustainably and legally and will not be detrimental to the species' survival.

Puerto Rican boa (Epicrates inornatus)

Description

The Puerto Rican boa is a nocturnal species that mostly remains concealed or basks during the day. This non-venomous species is endemic to the main island of Puerto Rico and is the largest snake species on the island. Puerto Rican boas are viviparous, meaning the females do not lay eggs but give birth to live young.

Habitat

The Puerto Rican boa is considered a habitat generalist and tolerates a wide variety of habitat types (terrestrial and arboreal). These include: rocky areas and haystack hills, trees and branches, rotting stumps, caves (entrances and inside), plantations, various types of forested areas such as karst and mangrove forests, forested urban and rural areas, and along streams and road edges. Cave ecosystems and their surrounding forests are considered particularly important because of the availability of ecological resources such as prey, shelter, thermal gradients, and mates for reproduction. Nearly half of the island is considered habitat for the Puerto Rican boa.

Threats

The most influential threats for this species are habitat loss and fragmentation from human development, predation from exotic mammals (in particular domestic cats), and poaching and intentional killings. Other known threats include factors that reduce or degrade available habitat and may directly impact the species, as well as mortality from roadkill, human persecution, and emergent diseases. Puerto Rican boas have been translocated as a management strategy to minimize conflicts with the public and minimize potential effects from development projects that disturb and modify their habitat. This primarily consists of moving boas outside the human-boa conflict areas into areas into areas where these conflicts are reduced, such as within suitable protected areas.

There is no additional information to suggest that the Puerto Rican boa has been or is being significantly impacted by trade. Although the species continues to be threatened by unregulated local hunting to extract oil for medicinal purposes or to be kept as pets, this practice probably occurs on a small scale. A recent five-year review indicated that down-listing from CITES Appendix I to II would neither have a conservation impact on this species nor affect the nature of the trade.

Redfish sea cucumber (Thelenota spp. [3 species])

Description

The three Thelenota species are different from other sea cucumber species, partly due to their large papillae or protuberances. Thelenota is a genus of widely distributed sea cucumbers commercially exploited for consumption and threatened by the international beche-de-mer trade. Beche-de-mer is the product after gutting, cooking, salting, and drying sea cucumbers. Demand is primarily in Asia.

These three Thelenota species play an extremely important role in maintaining the health of coral reef ecosystems in the Indo-Pacific region, including regulation of water quality, nutrient recycling, and promotion of productivity and biological diversity.

Habitat

Thelenota anax occurs throughout the Indo-Pacific. T. ananas is widely distributed throughout the Indo-Pacific, excluding Hawaii. T. rubralineata is found only in the east Pacific. All three species are all reef-associated and will be impacted by declining trends in reef habitat health. Despite their commercial importance, little is known about the biology, ecology, and population dynamics of these species.

Threats

As some of the highest-value sea cucumber species in international trade, these animals continue to be widely exploited because of their perceived unique biological and pharmaceutical properties. However, the pharmaceutical and cosmetic products that contain sea cucumber extract do not typically reference the source species. T. ananas has suffered substantial declines across its range, and the rarity, price, and suspected life histories of T. anax and T. rubralineata suggest high vulnerability to overexploitation. Trade in sea cucumbers is typically unselective, with the market shifting to other species as soon as targeted species have been depleted. Significantly, there are no international measures to ensure that harvest is sustainable, and no Regional Fisheries Management Organization manages or coordinates management of sea cucumbers. An Appendix II listing will provide transparency to this trade and ensure speciments entering international trade are acquired sustainably and legally and will not be detrimental to the species' survival.

Rhodiolia spp. (58 species)

Description

Rhodiola is a diverse genus of perennial herbs with a wide distribution spanning across the northern hemisphere. Although species within this genus are found across a wide altitudinal range, they are commonly associated with subarctic and alpine areas. Members of the genus are generally long-lived and slow growing, sometimes taking 20 years to reach maturity in the wild. The horizontal underground stems (or rhizomes) of some species of Rhodiola, known as “roseroot”, have historically been part of traditional medicine systems across most of the genus’ range. With several clinical trials investigating the effectiveness of Rhodiola rosea-containing products in treating the effects of fatigue, sleep disorders, and depression, international demand is further projected to increase.

Threats

Harvesting is based on the exploitation of the large rhizomes (rootstocks) and/or whole plants, and the majority of material currently traded is wild-sourced. In addition, harvest is focused on reproductively mature individuals, so commercial levels of exploitation have an increased potential to impact recruitment and long-term population viability. Estimates suggest that trade volumes are considerable; for example, in a single year, shipments of Rhodiola products were estimated to contain 2,464 kg of the concentrated extract, which could correspond to anywhere from approximately 94,000 kg to 312,320 kg of dried root and rhizome raw material.

End products include cosmetics, teas, capsules, and tinctures. The raw material is also used to extract and isolate pharmacologically active constituents in drug discovery and development. Although artificial propagation of Rhodiola species is possible, the current scale is small and there are few commercial growers. There are no known international instruments or controls in place that specifically relate to Rhodiola species to either protect or regulate the use of the species across international borders.

Straw-headed bulbul (Pycnonotus zeylanicus)

Description

The straw-headed bulbul sings frequently throughout the entire year, often with two or more birds singing together. The song of the straw-headed bulbul contains powerful, repeated two-note phrases with rich, melodious, bubbling, rising and falling cadence. The species also emits semi-constant low gurgles or weak chattering when foraging and prior to roosting. This species is a large, predominantly brown bird with a yellow crown and white streaks on its chest. Its face is also yellow with two prominent black stripes.

The straw-headed bulbul breeds between January and September, constructing large and shallow nests in trees a few meters above the ground. A breeding pair generally lays two eggs in a clutch, and the eggs and chicks are raised by both parents. These birds consume berries and fruit, swallowing them whole and dispersing the seeds. They are also known to also eat small invertebrates and lizards and can catch flies and beetles while in flight. Unlike many forest bulbuls, the straw-headed bulbul often feeds on the ground.

Habitat

The straw-headed bulbul occupies successional habitats bordering rivers, streams, marshes, and other wet areas, usually bordered by broadleaf evergreen forest and secondary growth. This is a predominantly lowland species. Its habitat is decreasing throughout its range, primarily due to logging and development, including clearance for agricultural plantations.

Threats

The straw-headed bulbul is declining extremely rapidly across its range. Trapping of wild birds for the cage-bird trade is the main threat, compounded by habitat loss within its rather specific habitat type. The straw-headed bulbul's loud, distinctive calls make it easy to locate them in the wild. Nests are usually constructed in accessible areas, making them relatively easy to spot and trap.

Little to no information exists on the population structure of this species. However, trappers focus on capturing adults by virtue of the methods they use—listening for its calls to find nesting groups and capturing roosting birds by rivers. Adults are likely captured more often, and with the adults gone, many young are unlikely to reach maturity. Their commercial value is widely known even in remote areas, resulting in continued attempts to trap and sell the birds and adding to trapping pressure.

Short-tailed albatross (Phoebastria albatrus)

Description

The short-tailed albatross is a large pelagic bird with long, narrow wings that are adapted for soaring above the water surface. The short-tailed albatross is the largest albatross species in the North Pacific.Adult short-tailed albatrosses have a white head and body, and golden cast to the crown and nape. The tail is white, with a black terminal bar. A disproportionately large pink bill distinguishes it from the other two North Pacific albatross species, the Laysan albatross (Phoebastria immutabilis) and black-footed albatross (P. nigripes), and its hooked tip becomes progressively bluer with age. Short-tailed albatross juveniles are blackish-brown, progressively whitening with age and are the only North Pacific albatross that develops an entirely white back at maturity.

Habitat

These seabirds' nest on isolated, windswept, offshore islands, with restricted human access. Their habitats, breeding habitats, and foraging habitats have become protected areas, national wildlife refuges, national monuments, and marine protected areas. The majority of short-tailed albatross nest on islands near Japan. The only known nesting in the United States occurs in the Hawaiian Archipelago. Short-tailed albatross spend most of their time at sea searching for food.

Threats

Historic exploitation of short-tailed albatross for their feathers is no longer a threat to the species, as there is currently no commercial harvest. Commercial trade in the species has been minimal, consisting of only pre-convention specimens traded in 2004, with all other trade being scientific. There is no trade demand for short-tailed albatross, and no evidence that international trade is or may be a threat to the survival of this species.

Short-tailed albatross are still exposed to the threats of bycatch from commercial fisheries in the United States, Russia, and Japan. Like many other seabirds, this speices will get hooked or snagged from longline fishing vessels, both pelagic and demersal, from attacking the baited hooks they deploy. When this happens, the bird can be dragged underwater and potentially drown. Between 1990 and 2004, incidental take rates decreased substantially -- by roughly 70 percent -- when streamer lines were free to obtain.