2018: Cool, salty gales sweep the surface of the Chukchi Sea, stinging the faces of three Wildlife Conservation Society scientists as they depart the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Research Vessel Tiĝlax̂ and skiff to the shores of Cape Thompson in Alaska’s North Slope Borough.

More than 100 miles north of the Arctic Circle, life thrives in this coastal mosaic of emerald and azure. Lagoons dominate, their waters and vegetation a haven for shorebirds, waterfowl, caribou, and migratory fish, including Pacific salmon and herring. The subsistence harvest along and off these shores – just 30 miles south of the Iñupiat village Tikiġaq (Point Hope) – is bountiful, having supported Indigenous lifeways since time immemorial.

And yet, if not for these local communities and their voices, this land may have been lost completely, some 70 years ago, to the Atomic Era and industrial ambition.

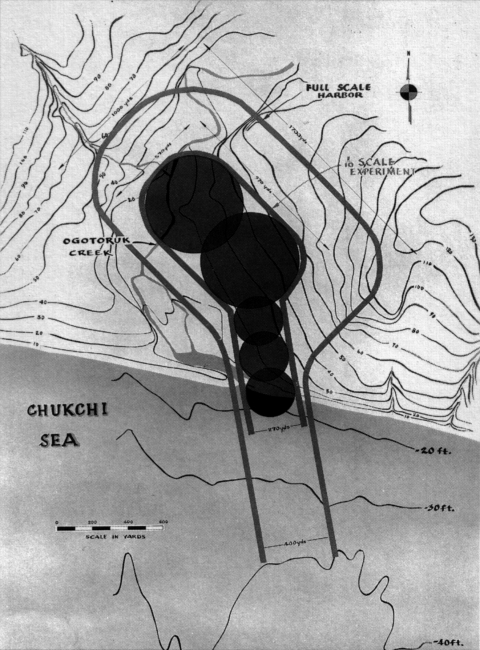

In the 1950s and ‘60s, as the United States experimented with “peaceful” uses for nuclear weapons, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission proposed the detonation of five hydrogen bombs in the Ogotoruk Creek Valley, just south of Cape Thompson. The effort, named Project Chariot, sought to clear land for the construction of a shipping harbor and storm shelter.

Iñupiat residents successfully urged the commission to reconsider. They expressed the land’s cultural and ecological significance, communicating the permanent destruction such blasts would wreak on its ecosystems and subsistence users.

Chariot’s leaders acknowledged these concerns, though only to an extent – while no bombs were detonated, extensive drilling and nuclear testing continued. Extreme soil contamination contributed to the region’s elevated cancer rate, which remains today one of the highest in the country.

Project Chariot also commissioned environmental studies. For several years in the late 1950s and early 1960s, dozens of researchers populated a tent city at Ogotoruk Creek. Their focus areas included caribou, plants, geology, marine and freshwater fish, and lagoon ecosystems. Though millennia’s worth of Indigenous Knowledge of the region already existed, it was the first time that government-directed environmental studies were conducted. At last, in 1962, to the relief of Indigenous communities, Chariot altogether was shelved.

More than a half-century later, as the destructive legacy of Chariot persists, these initial environmental impact studies are nonetheless a valuable baseline for climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change researchers: offering valuable data, especially given the current Arctic amplification of climate change effects and increasing interest in development in and around Cape Thompson.

An eroded airstrip and one small cabin off the coast of Cape Thompson are all the infrastructure remaining today to fossilize Project Chariot, and these remnants were among the first views for the freshly arrived crews of Wildlife Conservation Society and U.S. Fish and Wildlife scientists in 2018, and again 2021, to what is now coastline of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge.

The teams returned in two different trips to follow-up on these initial environmental research efforts, hoping to assess current conditions and document any changes evident in these previously-studied ecosystems.

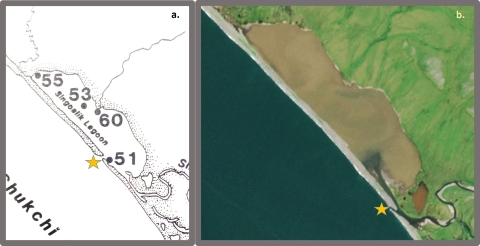

The researchers prioritized five lagoons: Singoalik, Atosik, Kemegrak, Mapsorak, and Akoviknak. At each, field crews collected water chemistry readings, zooplankton net tows, and waterbird observations – they encountered Arctic terns, glaucous gulls, Arctic loons, small shorebirds, mew gulls, tundra swans, jaegers, and ducks.

To measure fish diversity and abundance, crews used beach seines to capture small-bodied fish along lagoon banks, and tangle nets to catch larger fish swimming further from shore. The fish that were caught included least cisco and humpback whitefish, which are important subsistence harvest species, as well as starry flounder, marine sculpins, sticklebacks, capelin, and pond smelt.

With high rates of coastal erosion in Northwest Alaska, plus increasing severity of beach-altering storms, the teams also wanted to put an assumption – that lagoon geography in Northwest Alaska is fairly stable – to the test. Scientists analyzed satellite imagery, collected from 2016 through 2021, to assess how often, and for how long, these five lagoons remained connected to the sea.

Despite a brief disruption due to the Covid-19 pandemic, conclusions from the two studies pointed to the uniqueness and resilience of Cape Thompson’s lagoons, decades after the influence of Project Chariot.

Within any one lagoon, zooplankton and fish populations were shown to remain consistent over years or even decades, while remaining distinct from other lagoons. This offers subsistence harvesters, fish, waterbirds, and marine mammals a “smorgasbord” of different food options along the Chukchi Sea, promoting adaptability in the face of climate change.

The studies also stressed the importance of lagoons’ connections to marine ecosystems, which, crews found, may change over the span of several decades. These connective channels (if present) heavily influence each lagoon’s biodiversity and water chemistry – Singoalik, for example, was the only lagoon with seasonal brackish water.

Protections against marine oil spills, human development, and coastal erosion, the researchers concluded, should be focused around these connections, which are spatially small, culturally and ecologically significant, and disproportionally vulnerable.

More information:

Detailed information from the WCS 2018-2021 Cape Thompson Lagoons study is available in a report here: https://doi.org/10.19121/2022.Report.44211. “The Firecracker Boys” by Dan O’Neill presents an excellent overview of the Project Chariot story. Reports from environmental studies associated with Project Chariot (1) and Red Dog Mine (2) are listed below and are best accessed through the Alaska Resources Library and Information Services (ARLIS).

1. Wilimovsky, N. J., & Wolfe, J. N. (Eds.). 1966. Environment of the Cape Thompson Region, Alaska (Vol. 481). United States Atomic Energy Commission, Division of Technical Information.

2. Dames, A., & Moore, R. 1983. Environmental Baseline Studies, Red Dog Project. Cominco Alaska, Inc.