On a picture-perfect, mid-September Monday, a dozen staff from the Maryland Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service caravaned down a rutted dirt road in a Wildlife Management Area to witness a conservation milestone.

Upon exiting their vehicles, attendees gathered around a few five-gallon tanks at the edge of a small pond. The tanks contained tiny fish — about the size of a quarter — whose yellow-green bodies with dark vertical stripes glowed in the early fall light.

After celebratory remarks, biologists from Maryland DNR’s Fishing and Boating Services scooped the fish into five-gallon buckets and released them into the pond, where they slipped out of sight in water the color of black tea.

It was the first time the state released captive-bred blackbanded sunfish into the wild — the result of a strategic, long-term effort to bring the rarest freshwater fish species in Maryland back to its native habitats, made possible with the support of many partners, State Wildlife Grants awarded through the Service’s Office of Conservation Investments, and a 2024 grant from the Chesapeake WILD Program.

The Service launched Chesapeake WILD in 2022 in partnership with the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation to support partner-led efforts to sustain the health of the six-state watershed and its inhabitants, including fish and wildlife species like the blackbanded sunfish.

“Where we are now — with successful propagation and release to augment a population, and more — is the culmination of nearly 20 years of work,” explained Jay Kilian, a state natural resource biologist who has been involved in this effort for much of his career.

While there's still a ways to go to secure this species’ future in Maryland, the September release was a big step for a small fish.

Back in blackwater

Blackbanded sunfish depend upon “blackwater” habitats, once abundant in the coastal plain. Named for the natural dark stain from organic materials leaching from the soil, these wetlands are acidic and nutrient poor, home to a small suite of well-adapted species.

Over the last couple of centuries, Maryland’s blackwater swamps were drained, leading to loss of both the physical habitat and the unique water conditions that support species like the blackbanded sunfish.

“What we are left with is pockets of blackwater in Maryland, as well as in Delaware, but without the connectivity between them to sustain populations,” Kilian explained. “Everything that remains here is highly isolated — and vulnerable for that reason.”

Since 2008, Maryland has collaborated with partners in the Chesapeake Bay region to develop and implement an interstate conservation strategy outlining specific actions to protect and restore populations of the blackbanded sunfish.

“One of the primary actions was to survey for them using as many methods as possible, which affirmed that these fish were nowhere to be found in Maryland,” Kilian said.

Well, almost nowhere. They do occur at one site, but a genetic analysis revealed the fish there are highly inbred.

Confirming the near absence of the blackbanded sunfish inspired a new strategy: develop and implement captive propagation, also called captive breeding, to augment the existing population and establish new ones where suitable habitat remains.

But how do you breed a fish that is nearly gone and largely inbred? The saving grace for the blackbanded sunfish, and the people working to bring it back, is that it’s still thriving somewhere else.

Pineland of the lost

“Ever been to the New Jersey Pinelands? Historically, the eastern shore of Maryland was much more like that,” explained Jason Cessna, a biologist with Fishing and Boating Services who did his master’s thesis at Frostburg State University on blackbanded sunfish.

If you haven’t been, picture rolling sandy hills, covered with dense forests of scruffy pine and oak, with blackwater swamps and ponds in the lowlands connected by rivers and streams. Thanks to the protections of the New Jersey Pinelands Protections Act, the blackbanded sunfish and its habitat remain healthy in the Garden State.

“In our last comprehensive review, we documented blackbanded sunfish in more than 100 distinct locations, where they were heavily abundant in most sites,” said Scott Collenburg, a biologist with the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection’s Fish & Wildlife.

“New Jersey plays a unique role in the long-term survival of this species because most individuals are found in the Pinelands Preserve,” Collenburg said. “We feel a responsibility to support conservation across our border.”

In 2016, Maryland DNR contacted the National Aquarium in Baltimore about partnering to pilot a blackbanded sunfish captive propagation program.

“It was a perfect match in a lot of ways,” explained Ashleigh Clews, curator of the aquarium’s animal care and rescue center. “The state wanted to collaborate with a facility that had fish husbandry expertise, and we are always looking for ways to support local conservation initiatives.

Given the precariousness of Maryland’s population, the partners knew they needed to find another source. So, Maryland reached out to New Jersey to ask if they could collect from lakes with healthy blackbanded sunfish populations.

“We started our monitoring program in the 1950s, so we have good documentation of where these fish occur,” New Jersey’s Collenburg explained. “That allowed us to select water bodies where we’re confident the populations are robust.” In these ponds, he said, a single sweep of a seine net will bring in 50 fish.

As a precaution, Maryland’s Cessna conducted a population estimate in seven of the lakes, providing reassurance that the numbers were high.

Something in the water

Based on these assessments, Maryland collected 50 fish from New Jersey in 2017 and brought them to the National Aquarium as broodstock broodstock

The reproductively mature adults in a population that breed (or spawn) and produce more individuals (offspring or progeny).

Learn more about broodstock for the pilot propagation effort.

But the fish didn’t survive long enough to attempt breeding. Having adapted to acidic, tannic water, they couldn’t tolerate conditions that most fish thrive in.

“We have clean water with perfect chemistry — but that’s not what blackbanded sunfish want,” Clews said.

Aquarium staff began to do research and tests to figure out how to optimize conditions in the tanks but had to put the project on hold when the animal care department moved into a new offsite facility in 2018.

Right when they were ready to dive back in, COVID-19 hit.

“We kept in touch with the state but couldn’t really move forward for a couple of years,” Clews said.

By the time state biologists were able to get back into the field to collect more blackbanded sunfish in 2023, aquarium staff had figured out one key to keeping the fish happy: bringing back water, and muck, from their home ponds, to help the fish acclimate and give the staff raw ingredients to replicate. Today, one of the aquarists makes his own pondwater for the blackbanded sunfish, using natural materials to start the “brewing” process months before they arrive.

Temperature and light are also important factors. The fish need a cool-down period in the winter, and a warm-up period in the spring. It needs to be dark in their tank at night, and light during the day.

“We’ve been playing with those variables, as well as dosing the tanks with Co2 to key into the right pH levels,” Clews said.

After years of trial, error, and interruption, in September 2024, staff from the aquarium and Maryland DNR collected 40 fish from two different ponds in New Jersey, brought them back to Baltimore, and for the first time, got them through the acclimation, holding, and quarantine periods.

“A year later, we still have 39,” she said.

Setting the stage

Meanwhile, conservation partners have been working on the ground in Maryland to set the stage for the anticipated return of blackbanded sunfish.

“We still have some nice, mature cedar swamps on the eastern shore, so we have been focusing on restoring the areas surrounding them to expand this habitat,” said Deborah Landau, director of ecological management for the Maryland/DC chapter of The Nature Conservancy.

She explained that the pulpwood industry drained and filled many wetlands in the area, before planting loblolly pine plantations. Nassawango Creek, now a 10,000-acre preserve managed by The Nature Conservancy, was 40% pine plantation when the organization purchased the land, in bits and pieces.

Over time, they’ve transitioned it back to a mix of native oak and pine, Atlantic white cedar and grasslands by restoring hydrology, conducting controlled burns, and planting trees in partnership with the National Aquarium’s Conservation Department.

“We’ve restored the physical properties and brought back native plant communities, now we’re excited to welcome back a species that has been lost for a long time,” Landau said.

Right place, right time

The Chesapeake WILD grant came in at the right place and time for this complex, decades-long, multi-partner conservation initiative.

“In addition to funding shovel-ready projects, the program provides grants for planning and technical assistance to support initiatives that simply need a catalyst,” said Mike Slattery, Acting Deputy Assistant Director for Science Applications. “The intent is to help partners clear hurdles to achieving their conservation goals”

After Maryland recovered from the initial setbacks with blackbanded sunfish captive propagation, Kilian said, “We knew we needed to build in some redundancy through a strategy that offered multiple pathways to success. The Chesapeake WILD grant provided the opportunity for partners to pool resources in a way that wouldn’t have been possible otherwise.”

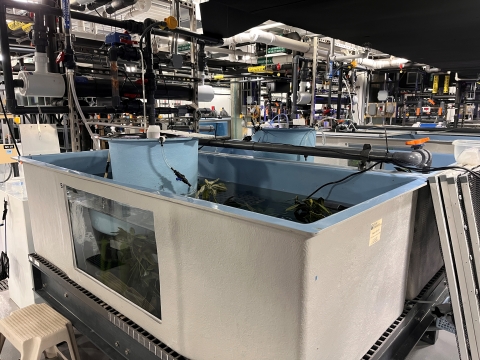

The grant allowed Maryland to invest in captive propagation of blackbanded sunfish in state-run facilities, capitalizing on the expertise of Maryland DNR hatchery staff and building on lessons learned from the National Aquarium.

“We now have both an indoor aquaculture system and a pond dedicated to blackbanded sunfish at one of our hatcheries, and the staff there have made enormous contributions to successfully propagating and rearing this species,” Cessna said.

Excitingly, the blackbanded sunfish that were released in September were born at the state hatchery just a few months prior.

“Given past difficulties, we weren’t sure we would have success in 2025, but because of the dedication of our hatchery staff they spawned successfully in captivity, and we had a high survival rate,” he said.

The grant also supported the National Aquarium, allowing them to upgrade their systems so they can better calibrate conditions in the blackbanded sunfish tanks.

And it funded the planting of 1,500 Atlantic white cedar trees as part of the effort to restore blackwater habitat at The Nature Conservancy’s Plum Creek Preserve near Sharptown, Maryland. The planting was led by the National Aquarium’s Conservation Department with assistance from the Maryland Conservation Corps.

In the grand scheme of things, the recent progress could be seen as a drop in the bucket. Once Maryland has built up robust populations of these fish in blackwater ponds — which will take time — the ultimate goal is to get them out in streams and rivers in the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

But the ripple effects of this grant are far-reaching.

“This small grant leveraged a lot of attention toward this species,” Kilian said. “We have a lot of momentum now; I hope it continues.”