With a career longer than many of his colleagues have been alive, Maurry Mills is still passionate about conservation 50 years into his tenure with the Service.

A Northeast native, Maurry was born in New Jersey.

“Actually, when I was first born, my parents lived on what’s now part of the Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge wilderness area. My grandmother owned a small farm in the area there … so when I was in grammar school and even in high school, we used to go back and tromp around in the swamp there just looking for animals and doing what kids do — exploring nature.”

This fascination with nature carried through to his adolescence.

“When I graduated from high school in 1970, I originally thought I might like to go into marine biology, but one summer I was looking for a job and my grandmother said, ‘Why don’t you go see the wildlife down there?’ so I went over and met with the refuge manager at Great Swamp.”

Maurry was hired in 1971, working part-time that summer as a student aide making $1.60 an hour.

He continued to work part-time at Great Swamp in college, commuting back and forth between the refuge and Rutgers University. He received a bachelor’s degree in wildlife biology in 1975.

After many temporary appointments, Maurry became a permanent employee at Great Swamp in 1976. He didn’t stay put for long, though.

The next year, he was hired as the first full-time employee at Maine’s Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge. In 1985, he took a new position at Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge, near the border of eastern Maine and Canada. Maurry was excited by the challenges presented by Moosehorn’s heavily forested land, which differed from the salt marsh habitat at Carson Refuge.

And he still is.

Moosehorn is part of the Northern Maine National Wildlife Refuge Complex, which includes Aroostook and Sunkhaze Meadows national wildlife refuges, along with Carlton Pond Waterfowl Production Area. For the past 39 years, Maurry has guided conservation across the landscape, beginning as Moosehorn’s assistant refuge manager and moving to his current role as wildlife biologist for the complex in 1993.

Maurry’s favorite part of the job is “getting to work in a place like this where I can go out and do my work out in the field and have a chance of seeing a variety of different wildlife and habitats. I also enjoy working with our seasonal interns and technicians, many of whom wind up with jobs in the wildlife or forestry fields.”

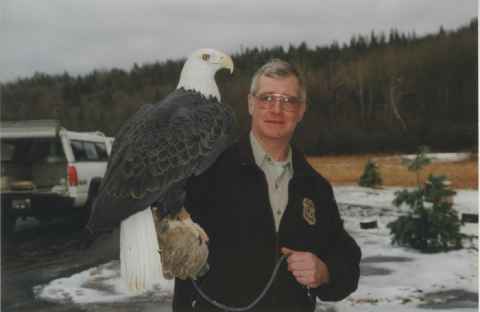

Though Moosehorn’s wildlife population ranges from black bears and moose to river otters and mink frogs, bald eagles are Maurry’s favorite. It’s no wonder then that he jumped at the opportunity to work closely with one.

For 15 years, Maurry cared for Bart — a permanently injured bald eagle. Maurry and Bart visited every school group in Washington County to teach students to appreciate eagles and other raptors, in the hopes of curtailing needless shootings taking place at the time. They also did many public events throughout the state, including several with the Passamaquoddy Tribe.

There have been many strides made in conservation technology in the past 50 years. Having used a computer with a 35-megabyte hard disk at the beginning of his time at Moosehorn, Maurry has not resisted technological advancements.

“I enjoy setting up databases and tracking things ... I do a lot of GIS work, which I learned by self-teaching and attending workshops.”

Maurry uses GIS to map habitat, record bird survey data and determine the features of land eligible for refuge acquisition.

“I took aerial interpretation in college. We were using Mylar sheets and overlays of paper aerial photographs. Now everything's done on the computer, and it's incredible.”

When he isn’t saving wildlife, Maurry enjoys chatting with people using radio frequency waves. In other words, he’s a licensed amateur radio operator.

“I have my own radio station, where I can talk to people all over the world. I was able to get W1FWS as my call sign.”

You must be licensed by the Federal Communications Commission to use “ham radio” in the United States, but this is no problem for Maurry.

“I’ve got the highest class license you can get in the U.S. I communicate using my voice or Morse code.”

Maurry connects with conservation outside of work as well. He helps coordinate two local Christmas bird counts and has contributed to the Maine Breeding Bird Atlas. He's one of the founders of the Downeast Spring Birding Festival, which will take place for the 21st time this Memorial Day Weekend. He serves on the planning committee and as guide for several events on and off the refuge.

Maurry enjoys hunting for grouse and woodcock with Sadie, his French Brittany. He says, “It’s fine if I get some game. If not, I just like going out and watching Sadie work the covers. Just getting out and being outside with her, being out in the woods and seeing other wildlife — is satisfying for me.”

Maurry also likes to fish both fresh and salt water and tend his vegetable gardens.

With no immediate plans to retire, he hopes to continue his work with the complex as long as possible.

“I just enjoy the hands-on wildlife and the GIS type of work that I do now. ... When I first started, I was in refuge management. We did a lot of administrative-type office work. I'd rather do biological work and have the opportunity to be out in the field.”