You could say Dan Grout’s career in wildlife biology began in third grade when he learned desert kangaroo rats are one of a few species of mammals that do not need to drink water to survive.

“They can actually metabolize the water they need from the carbohydrates in the seeds they eat, they are amazing!"

Grout never lost his curiosity for these small hopping creatures. He worked for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Colorado, California, Hawaii and many remote Pacific islands monitoring endangered species, but for him the kangaroo rats of California are among his favorite. He left the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to form his own consulting firm, focusing on small mammals, including the kangroo rat.

Today, he is one of the foremost experts on Stephens’ kangaroo rats, having studied them in the field for more than 30 years.

Although it’s name includes both “kangaroo” and “rat,” it is not closely related to either. It is instead a close relative of the pocket mice, so called because of the fur-lined cheek pouches they use to carry seeds in.

It has a crisp white racing stripe running from its back legs to the end of its long tail. Night vision, long whiskers and acute hearing help it navigate the night as it forages for seeds and aims to avoid predators such as snakes, owls, bobcats and coyotes.

In 1988, the same year Grout started working with the Stephens’ kangaroo rat, it was listed as federally endangered, mostly due to loss of habitat from development. Currently, the species is restricted to small pockets of habitat across its former range in the grassland valleys of two counties in Southern California: San Diego and Riverside.

As a biological consultant, Grout monitors various sites for Stephens’ kangaroo rats to determine how the population and habitat are faring. One of those sites in San Diego County happens to be part of a naval weapons storage facility - Naval Weapons Station Seal Beach - Detachment Fallbrook, located in the rolling hills of the northeast corner of Camp Pendleton and 10 miles southeast of Temecula, California.

Peter Beck, wildlife biologist for the Service's Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office, works closely with several military installations in Southern California, including Detachment Fallbrook, providing assistance in developing and implementing Integrated Natural Resources Management Plans.

Unique among most naval weapons facilities, Detachment Fallbrook is located nine miles inland.

The Director of Detachment Fallbrook, Tony Winicki, said that due to the installation’s specific operations, it has the open space and capability to help imperiled wildlife.

“This is a species that’s been stressed with all the development across San Diego. The Detachment has been a safe haven, mainly because of the short-term and long-term management we’ve done and because we’ve maintained a space for them to live,” he said. “Our installation’s mission makes it pretty easy to balance operations and conservation at Detachment Fallbrook. In the main area of the base, there’s a lot of activity, but we also have a lot of undeveloped, open land.”

Peter Beck, wildlife biologist for the Service's Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office, works closely with several military installations in Southern California, including Detachment Fallbrook, and provides assistance and input as the installations develop and implement Integrated Natural Resources Management Plans.

“We have a very cooperative relationship with Detachment Fallbrook,” said Beck. “Detachment Fallbrook regularly solicits our input on the management of sensitive species as they update their Integrated Natural Resources Management Plan. Through these conversations, we promote the recovery of listed species that occur on Detachment Fallbrook, like the Stephens' kangaroo rat,” he added.

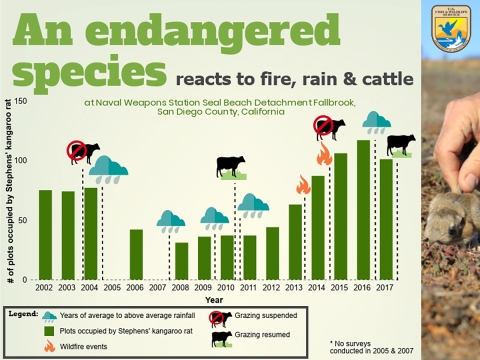

Annual Stephens’ kangaroo rat population surveys conducted by Grout beginning in 2001 reveal the distribution and abundance of this species fluctuate with the condition of the landscape. “Their preferred habitats are sparsely vegetated grasslands where they can hop, move and forage easily, which is not surprising, since they evolved for millions of years in western grasslands dominated by grazing herds of bison and other herbivores,” Grout said. “With those large wild herds now gone, cattle are now the main herbivore and this species can benefit from well-managed grazing.”

“In landscapes dominated by exotic grass, a level of grazing has been shown to be helpful because it removes crowded understories and unwanted weeds, said Christy Wolf, conservation program manager at Detachment Fallbrook. Credit: Joanna Gilkeson/USFWS

Over time, the importance of a grazing regimen to maintain healthy Stephens’ kangaroo rat populations on Detachment Fallbrook came into focus.

According to Christy Wolf, Conservation Program Manager for Detachment Fallbrook, “Cattle grazing has been used on Detachment Fallbrook as a fire management tool for decades. We knew grazing helped maintain the open grassland preferred by Stephens’ kangaroo rats, but it wasn’t until grazing was discontinued in 2004 that we appreciated the magnitude of the benefit.”

In 2004-05, more than 30 inches of rain fell on Detachment Fallbrook, causing invasive grasses to spread across the landscape. After several additional rainy winters and no cattle, Grout observed areas where thick thatches of exotic grasses were two feet high. By 2008, survey results indicated Stephens’ kangaroo rat populations dropped to less than half of what was recorded in 2004.

The benefit of grazing was made clear, yet initiating and maintaining a military grazing program was complex, and it took several years to restore the program on base.

Ranchers move cattle onto Naval Weapons Station Seal Beach Detachment Fallbrook in this 2014 photo. Credit: Ryan Lockwood/Detachment Fallbrook, U.S. Navy

In 2010, through an agricultural lease with a longtime San Diego ranching family, the Mendenhalls, cattle again grazed during the spring and early summer. They quickly consumed weeds and thick grasses. “After the grazing resumed, we found more and more kangaroo rats during our surveys. It was exciting,” said Grout.

Around the same time grazing was reinstated, a period of drought entered Southern California. The remaining vegetation became brittle and dry.

Risk of wildfire was high and in 2013 and 2014, two major fires rolled through Detachment Fallbrook. In some areas where cattle grazed and kangaroo rats foraged, the impacts of the fires were minimized. The flames even skipped over lightly vegetated, grazed patches of occupied kangaroo rat habitat.

The 2014 Tomahawk wildfire burns at the entrance to Naval Weapons Station Seal Beach Detachment Fallbrook. The Tomahawk Fire was the second largest wildfire in San Diego County that year. It burned more than 6,500 acres across Camp Pendleton and Fallbrook area, and more than 250 people in the area had to be evacuated. Credit: U.S. Navy

A cow grazes on Naval Weapons Station Seal Beach Detachment Fallbrook. “Cattle remove a huge amount of standing dry matter, a couple thousand pounds per acre per year, reducing the quantity and continuity of fuel for a fire that might come through here,” said Christy Wolf, conservation program manager for Detachment Fallbrook. Credit: U.S. Navy

“Cattle remove a huge amount of standing dry matter, a couple thousand pounds per acre per year, reducing the quantity and continuity of fuel for a fire that might come through here,” Wolf said. “Burn severity on the landscape was especially noticeable where we had a fence line between grazed and ungrazed areas.”

Still, grazing or no grazing, the fire removed much of the ground cover on base and the grazing lease program was put on a temporary hold.

Luckily, the kangaroo rats largely survived, protected in their burrows.

Cattle returned to the base after the much-needed rain in 2016-17 relieved conditions of drought and encouraged regrowth of the fire-stricken native plants and invasive grasses.

During Grout’s 2017 surveys, Stephens’ kangaroo rat populations again declined after the rainy season ended the drought, but because of cattle grazing in the spring of that year, the dip in population was not severe.

In fact, the 2017 population numbers were higher than survey results each year from 2001 to 2014.

Wolf and Grout see that the kangaroo rats respond well to grazing, and hope that the continued presence of cattle will boost and maintain their overall population on the base.

Both stress the importance of a well-managed grazing program. “In landscapes dominated by exotic grass, a level of grazing has been shown to be helpful because it removes crowded understories and unwanted weeds,” Wolf said.

“We know that grazing helps reduce risks of wildfire, but we didn’t necessarily expect it to benefit wildlife as it seems to have,” she added.

Winicki also appreciates the delicate balance between cattle, wildlife and military training on base. “I’m a Marine, and typically we think training first, but I see us being able to balance the military’s mission and sustaining the environment. Conservation is part of our policy of being a good neighbor. Walking the walk and talking the talk is consistent with our mission,” he added.