The recovery of an endangered butterfly in southern San Diego made history recently.

A team of biologists from the San Diego Zoo Global, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, San Diego State University and the Conservation Biology Institute released 742 larvae of the endangered Quino checkerspot butterfly (Euphydryas editha quino) onto the San Diego National Wildlife Refuge last December, the first-ever captive-rearing attempts for this butterfly species.

In January, another 771 caterpillars were released, bringing the total to 1,513.

The Quino population drastically declined over the last decade. Losing the native pollinator could mean a strike against the balance of coastal sage scrub ecosystems here. But not on these biologists’ watch.

“This is the first time we’ve attempted to release Quino checkerspot butterfly larvae here, and we expect to learn a lot from our work here today,” said biologist John Martin, of San Diego National Wildlife Refuge. “It’s important to help the Quino maintain its maintain its distribution, and we hope they will thrive here and disperse to nearby suitable areas of the refuge.”

To save the butterfly, the team raised larvae in captivity in the San Diego Zoo’s Butterfly Conservation Lab, where zoo entomologists cared for the eggs, larvae and adults.

Their goal: A successful reintroduction into the wild and a new generation of butterflies to jump-start the population.

"Quino checkerspots have been reared in captivity in the past, but this is the first time that captive-reared Quino have been returned to the wild to augment wild populations," Martin said.

A member of the brushfoot family, the black, white, and orange-checkered 1.2-inch butterfly was once commonly seen south of Ventura County, ranging to the inland valleys south of the Tehachapi Mountains and into northern Baja California. The last time Martin spotted one on the San Diego National Wildlife Refuge was in 2012.

The butterfly’s rarity presented a challenge: How to capture enough butterflies to start the breeding program.

Since the Quino’s population was too low to gather adult butterflies from San Diego County, biologists had to resort to collecting them from the Riverside population, about 60 miles northeast of San Diego.

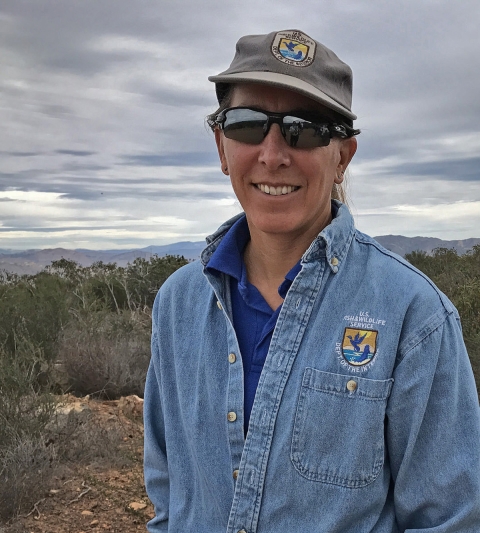

“The genetic work we’ve done indicates that Quino populations throughout their entire range are basically the same,” said Susan Wynn, a biologist with the Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office. “Although these populations are widely separated geographically, they are genetically similar and should have similar biological needs. So we think they should do quite well.”

In recent years, the species’ drastic decline was primarily due to the loss of its habitat from increased urban development. Climate change, drought, pollution, invasive plants and fire pose additional threats to the butterfly.

“Humans have had a significant impact on the decline of the Quino checkerspot butterfly,” said Paige Howorth, associate curator of invertebrates at the San Diego Zoo Global. “But humans are also playing a critical role in their recovery and today’s release is an important first step in doing that.”

At the zoo last summer, the new larvae from the captured butterflies were in a period of dormancy, called diapause. This is a natural condition that coincides with the lack of availability of their host plant, dwarf plantain. During this time, the larvae retreat into silken webs and cease all activity. The biologists released them to the wild in this condition.

Beginning this month, biologists will be checking the pods once a week, looking for signs of caterpillars.

When environmental cues signal them to “break” diapause and begin feeding this spring, the caterpillars will be in their new world.

[Note: The Butterfly Conservation Lab is funded by a USFWS Cooperative Recovery Initiative grant and mitigation funds from CalTrans for State Route 125. The long-term goal of the grant is to help this butterfly’s population recover sufficiently to down-list the Quino checkerspot butterfly from the endangered species list.]