About 15 years ago, at a wetland science conference, Vanessa Tobias presented early results from her Ph.D. research into the leaf-tissue chemistry of

wetland grasses. Tobias’ data, displayed on a poster next to her as she took questions in a conference hall, identified markers that could help land managers diagnose and address the causes of wetland loss.

“A guy came up and asked me where I got the data,” she recalled, “and I was really confused, and responded, ‘What do you mean? I collected it.’”

Tobias had taken soil samples, measured environmental variables, and built and installed elevated planters called marsh organs at sites across the Louisiana coast — all normal activities for a scientist in her field.

“I didn’t know how to answer him at first, but through talking to him, I realized he didn’t think women could do field work,” she said. “In my field, wetland science, there appears to be more women than men now, so it was really interesting to be at a wetland conference and have someone question, ‘You do field work?’ … But that attitude still exists today.”

Now a supervisory mathematical statistician for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Tobias’ job doesn’t call for field work. Instead, she’s one of several women who design and manage one of the largest, most complex fish-monitoring programs ever undertaken in California, the Enhanced Delta Smelt Monitoring program.

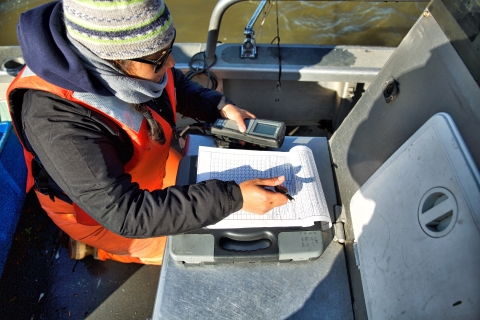

Since December 2016, the program’s field technicians have set out four mornings each week to gather information on the abundance and locations of Delta smelt in the upper San Francisco Estuary.

Data on the small, threatened fish caught in their nets — which could be fatally caught or diverted by water-pumping systems — are reported the same day to help guide partners overseeing water operations that serve millions of Californians.

“It’s exceedingly rare to have this real-time reporting component nearly every day,” said Stephanie Durkacz, supervisory fish biologist in the Lodi Fish and Wildlife Office. “I’ve never heard of or been a part of any scientific project like this. It’s historic.”

EXCITED BY THE CHALLENGE

Smelt monitoring program crews take samples each week from up to 40 sites, which are randomly generated in advance from an area covering more than 700 square miles. In a typical week, sampling crews cover more than 2,000 miles over land and water.

Catherine Johnston, who began working as a biologist in Lodi a few months before the smelt monitoring program’s launch and now manages it, said the Lodi office was well-prepared since it already ran the large-scale Delta Juvenile Fish Monitoring Program. But some challenges couldn’t be predicted until the smelt monitoring program was put into action.

“For probably the first year and a half, we were figuring out what was needed as we were doing it,” Johnston said. “Denise Barnard [of the East Bay Municipal Utility District] was in my position when the smelt monitoring program began, so she was the pilot of the plane that was being built as it was flying. I can’t imagine the stress of that position.”

To get it off the ground, the program needed more than 40 skilled employees and a variety of boats, vehicles, and specially fabricated equipment. Establishing the program — and continually refining its sampling design, statistical models, data management, scheduling, and logistics — required week-to-week adjustments, intense work, and extra hours. Fortunately, Lodi was the right place for the job.

“EDSM was very lucky to have gung-ho people who were ready for it,” Johnston said of the program. “It was new and challenging, but people were excited. I was excited by the challenge.”

‘WE’LL ALL GO FURTHER’

Tobias didn’t set out to become a mathematical statistician. While completing her Ph.D. in wetland ecology, she learned complex statistical methods to apply to her field work and discovered her passion for working with data.

“Working in wetlands, things are really complicated, so you need to learn more sophisticated statistical techniques to figure out patterns in the data,” she said. “It’s like a big puzzle every day, and I get to help solve it.”

As children, girls are just as interested in math and science as boys are, Tobias said. But they don’t always feel welcomed in those fields in school or in the workforce.

“There’s still an undercurrent,” she said. “People don’t know they’re doing it — it’s that unconscious bias thing. If you’ve been conditioned your whole life to think of the image of the scientist as Einstein, if that’s what you’re picturing in your head, it’s hard to see a woman as good at math and science.”

Men’s views toward women in science are shifting for the better, Tobias said, and with that change has come increased opportunities and resources. Whereas women in previous eras had to compete against each other for limited positions, the Lodi team supports each other and lifts each other up.

“We don’t worry about spots because we’re trying to be more inclusive and have more of a spirit of collaboration,” Tobias said. “It changes the way people think. We can all help each other, and we’ll all go further.”

THE WORK CONTINUES

When Durkacz began working on the smelt monitoring program in early 2017, she was gathering data firsthand as a field technician, trawling for smelt for up to 10 hours a day.

“It was a 6 a.m. start time, and there were lots of very cold, dark, wet mornings,” she said. “I remember sitting out on that boat in windy, crazy conditions while it was pouring all day, every day.”

Despite the weather, she loved being on the boat and loved the camaraderie. There was excitement about the new program, which the crews knew was getting attention from other agencies and conservation groups. As the smelt monitoring program progressed, the attention — and scrutiny — would only grow.

“It was very unbelievable to me, in the literal sense of that word, that the president of the United States was [talking publicly about] something I was directly working on,” she said. “It was weird. You couldn’t have chosen a more politically charged topic than water allocation in California, which added to the pressure.”

Durkacz accepted a supervisor role in July 2019 and initially enjoyed being a mentor and a leader of the program. After only eight months, though, her focus shifted to logistics and crew safety during the COVID-19 pandemic.

While many other field operations were being halted, Durkacz said they had to find ways to safely continue the massive monitoring effort. The crews’ schedules were changed to limit personal interaction, and procedures were adjusted to minimize the chance of virus transmission. Then nearby wildfires made the air hazardous to breathe, grounding crews for the better part of six weeks in August and September.

“I’m usually an, ‘I can handle this, I take things on,’ type of person, but it was an extreme challenge for me,” Durkacz said. “It was tough, and the pandemic did not stop impacting us either. But we’ve persevered through it, and I’m really proud of the program for that.”

SPARKS IN THE ROOM

Years of hard work have refined the program. Mathematical statistician Ken Newman, who preceded Tobias, is recognized as the “architect” of the program, and former deputy project leader Matt Dekar was crucial in preparing it for launch. In the years since, the smelt monitoring program team has made a series of modifications to improve its efficiency.

“There were a lot of challenges with EDSM, and I always felt like we were pushing to make the program more sustainable and resilient,” Johnston said. “We are finally reaching that point now, where things are more routine, and supervisors don’t need to be as hands-on with every aspect every day.”

The Delta smelt itself, on the other hand, has been on a downward trend. The number caught by the smelt monitoring program has dropped drastically in recent years, and there are now fewer in the wild than ever before.

“The population is doing very poorly right now,” Johnston said. “It’s motivating, to keep supporting EDSM and keep the program the best it can be at this very difficult moment for Delta smelt.”

The Service is finalizing plans to supplement the Delta smelt population by releasing hatchery-raised fish into the estuary. That effort will raise complex questions for the smelt monitoring program, which the Lodi team is eager to answer together.

“The women in our office are so smart, but sometimes we take for granted how much we know and how important it is that we have these skills,” Tobias said. “When we’re all in a room together, figuring something out, and everyone’s feeding off each other and ideas are flying, you can almost feel the sparks in the room.”