Dr. Gordon Alcorn had his eye on protecting the Nisqually Delta as early as 1928. “I was on a committee when I was still a student, to try to save the Nisqually Delta. We could see that it ought to be a sanctuary.”(1) As a professor at the University of Puget Sound (UPS) and a member of the Nature Conservancy and other prominent organizations, he used his influence to shape conservation history in Washington State.

Gordon Alcorn was born in Olympia in 1907 and lived on a farm by the Sound. “When I was pretty small, we came to Tacoma and we lived out there roughly where the mall is now, you know, and there was nothing there. We didn't have a road up to our house. We had to park in the field and walk up to our house. We were way out in the country, and I had to walk to school.”(1) He was an adventurous young man, exploring the Hoh River by canoe, climbing Mount Rainier in 1936, roaming the wild lands around Tacoma. “Where the gas plant is and Coca-Cola and all that, that was nothing but prairie and ponds. In fact, we used to skate out there in the winter on the ice.”(1)

His family didn’t have much money and spent a lot of time hunting and fishing for subsistence. He bonded with some older men who knew the outdoors well. “The fellows that I chased around with as a boy were old enough to be my father. They saw I had an interest in wildlife. So I went with them, went on field trips with them, spent many years with them as a boy… They were just businessmen or something. They just liked the wildlife and natural history. They were all more or less unlettered, I don’t think they graduated from college, any of them… You could go anywhere. We used to tramp all over… We’d go anywhere on the beaches. Nobody around. Nobody bothers you. Now, no. With affluence, with two cars and a boat on every trailer in the backyard and all kinds of roads and all kinds of money and all kinds of improvements, the environment is suffering.”(1) These experiences pointed him toward a lifelong interest in natural history.

He graduated from Lincoln High School in Tacoma in 1926. Gordon’s brother Arthur worked for a movie company

in downtown Tacoma. Arthur was attending business school and convinced his brother Gordon to take classes. “But Gordon didn't last a day or two before he decided it wasn't for him. He wasn't interested in the subject and instead spent his time in class looking outside at the birds,” related grandson Gordon Peterson. With his mentors, he continued to explore wild places. “We used to go down to Nisqually all the time. And we could see that it should be saved. And we got to the Fish and Wildlife Service on it, petitioning. And we had an article in the paper we had put up, displays in the public library and so on. But we got the Fish and Wildlife Service to look at it with the idea that they would buy it. But it could have been purchased for peanuts then. And they looked at it and they said, no, it isn't big enough. It isn't big enough to keep one sanctuary or one wildlife agent busy. So they turned it down. So really, I’ve been on that Nisqually thing since 1928, off and on, it languished during the war and that kind of thing, but it’s been in the back of my mind all of this time. So I can see that I live in a period [that is] unique, and I knew what freedom and what wildlife was…”(1)

He was a keen bassoon player in high school, and was offered a job playing bassoon at Paramount Theater in Seattle for silent movies. He thought about attending medical school but couldn’t afford it. He continued taking bassoon lessons in Seattle, then attended the College of Puget Sound (now UPS) on a music scholarship, playing in the symphony. He earned a bachelor's degree in 1930 and taught part time “right smack in the middle of the Depression. I think I made 140 bucks a month, something like that. And part time, that was pretty good. And then I commuted, in the evenings, and I went summertimes to university and got a masters in ‘33 and a PhD in ‘35”(1) from the University of Washington.

He married Rowena Lung in 1934, a budding artist, author, and teacher who would become noted for her portraits of indigenous people. She taught at the College of Puget Sound while he earned his advanced degrees. Like many people during the Great Depression, they had very little money. Family lore has them eating seagulls to get by. They were married 60 years and had one daughter, Patricia.

Dr. Alcorn taught at the University of Idaho in Boise for two years. Then he was president of Grays Harbor Community College, but discovered he didn’t like being an administrator. “I like the students and like teaching and like the fieldwork.”(1) He returned to UPS in 1946 as a full-time professor. His students called him “the gray owl” for his hair color and passion for birds. He taught himself photography, aiming to get “a colored photograph of every nesting bird in the northwest.”(1)

Gordon joined multiple professional organizations, such as the Ecologist’s Union. He helped found the Washington State chapter of the Nature Conservancy, and was on the national board of the Isaac Walton League.

Over time, he found it harder and harder to locate places he could take his students on field trips. “I used to take my students to South Tacoma swamp and we'd spend all day out there. Now there isn’t any swamp. They filled it in with garbage. As an example, the South Tacoma prairies are gone, the Parkland prairies are gone, areas along the beaches like Westport. You’d go down to Westport, no motels, no people, birds all over the place. Now it’s people.”(1)

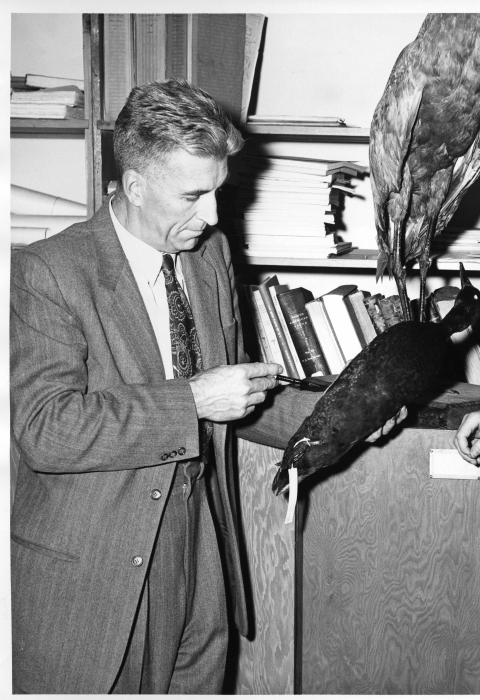

In 1951, he was named chairman of the biology department. He founded and for twenty years directed the Slater (now the Puget Sound) Museum of Natural History. He was especially proud of the museum’s collection of bird specimens and bird eggs. His nephew, Evan Jensen, recalls being welcomed and given a tour when he arrived from Germany to attend college at UPS. “He was very proud of his collection,” Evan recalls.

Dr. Alcorn had long used the Nisqually Delta as a place to take students on field trips. “The Nisqually Delta remained the only natural wild area within striking distance of the University of Puget Sound here; so I would naturally go down there. So for many years, I’ve taken students down there on field trips; and gradually through the years, built up an inventory of the birds and the mammals and the native plants on the delta.”(2) “It’s a very fertile region. We have found over the years something over 160 species of wild birds and almost 200 species of flowering plants of one kind or another. Most people, when they think of the delta, as far as the birds are concerned, think about the waterfowl. Of course, it’s a very important place for the resting waterfowl in the wintertime. But

actually, there are many more birds there than there are waterfowl, because it happens to be on the flyway, so that many songbirds, many perching birds, and a number of predators and the waterbirds of various kinds that are not ducks find food there and a resting area while they’re migrating. And I can take students there and know that I will see many birds that I cannot see now elsewhere in the immediate area of the delta. In fact, the Nisqually Delta is unique in that sense: there is no other terrain like it. The nearest is the Skagit in the northwestern part of the state of Washington. So that’s why we cherish the delta.”(2)

Dr. Alcorn’s opponents pressed for development on economic grounds. But he believed the value of land was not limited only to the money that could be made from it. “What is the highest use of the land? Now, if you destroy the land, you destroy the wildlife, and you don't get the land back. If you pollute the water or pollute the air, pollute the land, you can de-pollute. But you cannot get the land back. So we have to decide, is that land better used for this purpose or better used for this purpose? And there is a lot of land and there's a lot of controversy. A lot of people won’t agree, but there's a lot of land that ought not to be developed, that the wildlife, for education and for research and for—we’re not talking economics now-- for the aesthetics, for the soul, if you want to, whatever that is, is more valuable than the raw dollars we generate with that land. And the controversy arises, what is the best use of that land? That's where we get the trouble. That's where we get the problem. We cannot go along and have our cake completely and eat it too.”(1)

In lectures and interviews, Dr. Alcorn argued for conservation. “We view with alarm plans to do for the great delta of the Nisqually River what has been done to the Tacoma tideflats. It is probable that we will destroy in a few months, in order to build a port, what nature has taken a million years to construct. And so we will trade the beauty and the sanctuary of that peaceful region for the noise and pollution that has been wrought in the tideflats area.”(4)

The Washington State Legislative Council Committee on Parks and Natural Resources commissioned a study in 1970 from Dr. Gordon Alcorn of the University of Puget Sound and Dr. Dixy Lee Ray, then of the Pacific Science Center in Seattle. They were asked to provide information “for the purpose of determining a program for the development of the area for a wildlife and game preserve not inconsistent with the industrial development”(3) of the delta.

In the study, Dr. Alcorn and Dr. Ray pointed out the biological diversity of the delta and its status as the “least spoiled of all the major estuary deltas in the Puget Sound region.” They said, “It is a fragile treasure, a priceless and productive natural inheritance whose value is to be judged. It should not be weighed lightly.” They asked whether it was possible to have a clean superport and a wildlife refuge side by side. Their conclusion: “The answer is a simple and emphatic no.”(3)

Dr. Alcorn explained during a documentary film, “Now all you have to do is look at other cities where they built ports to see their development and how their wildlife has been destroyed. The two concepts are totally not compatible. You can not have port facilities and wildlife, too. Well, look at all the big cities along the coast, from San Francisco to Vancouver, British Columbia, or the City of Seattle, or even the City of Tacoma and its tideflats. You build the port, you destroy the wildlife. The two are totally incompatible.”(2)

Dr. Alcorn supported a Glacier to Sound Park idea, protecting the Nisqually Watershed from Mount Rainier National Park to the Nisqually Delta. He served on a 42-member task force appointed by Governor Dan Evans to explore the concept. The group agreed that the delta needed protection and recommended the creation of a wildlife refuge. They published a report, “The Nisqually Plan: From Rainier to the Sea,” in July 1972 calling on the state government to support creation of a federal wildlife refuge in the delta as well as to protect land within the watershed. In 1974, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service established the Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge.

Dr. Alcorn’s idea of how the Nisqually Delta might serve the public closely resembles the way it is used today. “We should remember that the delta is fragile. It cannot support very many people. The result of this is that probably trails, limited trails, could be built above the mudflats of the delta. Here, there could be nature walks, educational walks, under the guidance of educational experts and specialists. It would not do to open the delta to the public. It is too fragile, it is not possible for people to walk on it without supervision without destroying the wildlife and the natural values of the region.”(2) Over 400,000 visitors came to the refuge in 2024; but the trail system, much of it elevated boardwalk, is just four miles long, restricting the impact people have.

Reflecting on his experiences, he said, “I think my basic feeling as I look back is one of regret. I regret for the good old days and regret that we do not have today what we used to have. As an example, I cannot any longer take my students out in the wild and show them what I could have showed them twenty years ago. We cannot get away from industrialization, we cannot get away from people. We may hike in the mountains, we may meet a lot of people there, they may be there for the same reason we are. We cannot go places now that we formerly did, and now we realize that we no longer have these great resources that we had in the past. I think I am carefully optimistic, however, about the future. There are many people today who realize we are losing and destroying our resources. Many people realize that we had it, now we don’t have it. And we will have to do something about saving what is left.”(2)

In 1976, the UPS campus was named the Gordon Dee Alcorn Arboretum. Dr. Alcorn retired from full-time teaching in 1972, continuing to teach part-time and work in the museum until his full retirement in 1992. He died March 29, 1994. His wife died May 11, 1996.

But Gordon’s influence extends far longer than his own lifespan. The Gordon D. Alcorn Award is given out annually to the outstanding senior in biology at UPS. The Puget Sound Museum of Natural History continues to house the collection of birds and their eggs and other natural treasures he curated.

His great-grandson, Austin Alcorn Peterson, described his Pop as "very patient and engaged." Austin recalls countless walks in the forest. "Pop was always looking for teaching moments but wasn't at all forceful. He was a very intuitive teacher who made learning effortless.” He adds, “One of my earliest fond memories is when I went to a book signing in the Proctor district of Tacoma with Pop when I was 5 or 6.” The book, Birds and Their Young, was dedicated to Austin. Gordon authored several books on birds. "He left me with this idea of stewardship. That we can't just take but we need to think of future generations, always have to have the next generations in mind. This is what guided me to the Peace Corps.”

Countless students attended Dr. Alcorn’s classes over the years. Marcia Wolfe was a student of his, and published this recollection in Valley Ag Voice, Nov. 1, 2019: “I remember being in my basic required Biology class one day in college as an undergraduate years ago. Most of us know how it goes when taking a required course—there were a lot of students present who were just there because they had to be, not because they wanted to be. So, they weren’t interested in the material being presented. In this instance I recall the professor, Dr. Gordon Alcorn, a renowned West Coast ornithologist, talking about birds. Some of the students were getting restless and uninterested and the professor realized it. Then he stopped and said, ‘You aren’t interested in birds? Well, if you aren’t, you should be. If suddenly today there were no birds in the world, tomorrow when you wake up everyone in the world would be knee deep in dead insects.’ There was a resounding wow in the classroom as the students perked up with interest.”

It is likely Austin speaks for many of the people who learned from Dr. Alcorn when he said, “His lessons and teachings have stayed with me. As an adult I try always to carry with me the same thoughtfulness, patience, and dedication to the next generation that he brought to all he did.”

The national wildlife refuge national wildlife refuge

A national wildlife refuge is typically a contiguous area of land and water managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for the conservation and, where appropriate, restoration of fish, wildlife and plant resources and their habitats for the benefit of present and future generations of Americans.

Learn more about national wildlife refuge he did so much to help create is also still a draw to people who value wildlife and wild lands. Dr. Alcorn said, “Conservation is not just for conservationists. Everyone, young and old, rich and poor, is greatly affected by the forces that are both destructive and constructive that deal with this vital subject. We are called upon to use all our powers of ingenuity, persuasion, and economic resources… We must realize that we can only live in harmony with Nature—not conquer it.”(4) We celebrate Dr. Alcorn for his tireless efforts to protect the Nisqually Delta and other harbors of nature, and for helping to instill a conservation ethic in generations of students.

Sources:

(1): Interview with Ivan Doig for the Nature Conservancy.

(2): From the documentary “Ducks or Docks” by Paul Herlinger, Internet Archive, University of Washington, https://archive.org/details/WaSeUMCMISC001DucksOrDocks

(3): “The Future of the Nisqually Delta Area: a Memorandum Report to the Washington State Legislative Council, Committee on Parks and Natural Resources,” Nov. 9, 1970.

(4): “Shadow on the Land,” a lecture by Gordon D. Alcorn, John Dickinson Regester Lectureship, University of Puget Sound.