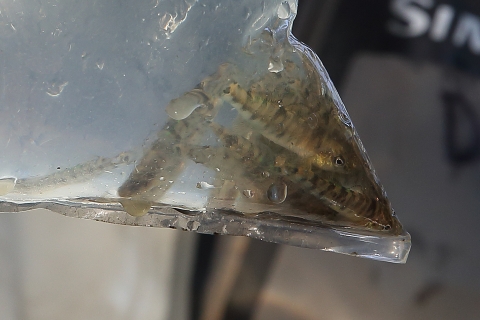

As recently as two decades ago, the Chesapeake logperch — a greenish-gold, zebra-striped fish no longer than a pencil — wasn’t considered a species. It was lumped in with the similar-looking but more common logperch.

But scientists had noticed subtle distinctions: the number of stripes, an orange band on one of the fins.

“We always knew they were different,” said Doug Fischer, a fisheries biologist for Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission.

Eventually, genetic testing by a researcher at Yale University confirmed their hunch — the Chesapeake logperch is one of a kind and found only in the upper Chesapeake Bay watershed.

Confirming it was a species also confirmed it was rare. It was difficult to find in the Susquehanna River and seemed to be absent entirely from the Potomac.

The Chesapeake logperch was at risk of disappearing from its namesake watershed.

All hands on deck

In 2017, the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and others, began a strategic effort to bring this fish back, starting by developing a range-wide conservation plan for the species.

Two years later, Pennsylvania and Maryland received a State Wildlife Grant from the Service to work with other partners to implement the plan and boost numbers of the Chesapeake logperch in the lower Susquehanna River and its tributaries, which all drain to Chesapeake Bay.

The multi-year project has produced results, including a productive captive-rearing program. From 28 Chesapeake logperch captured in the wild in March 2019, nonprofit Conservation Fisheries, Inc., spawned more than 1,500 babies in a matter of weeks — so many they had to stop because they were running out of space for them. It was the first time anyone had tried to breed the species in captivity.

Today, the Service’s Northeast Fishery Center, in Lamar, Pennsylvania, and the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission’s Aquatic Conservation Center in Union City, Pennsylvania, are also raising Chesapeake logperch in captivity and releasing them into the wild.

With some help from the partners, wild Chesapeake logperch are also playing a role in reestablishing populations across their historic range. Biologists have captured wild logperch from areas where they are doing well, tagged them, and released them in carefully selected streams where the quality of the water and habitat is high. To date, almost 1,200 of these wild-caught logperch have been rehomed in places where they are likely to thrive.

Every year, the team surveys these areas for tagged fish. Many have been recaptured — a promising sign for the partners and the species.

What’s more, they are also finding Chesapeake logperch without tags, suggesting the possibility of natural reproduction — the ultimate goal in streams where these fish have been long absent.

Giving species a chance to rebound

The collaborative effort to help the Chesapeake logperch is just one example of the proactive approach to conservation promoted and supported by the Service’s Science Applications program, in response to a growing need.

“Hundreds of species of fish, wildlife and plants in the Northeastern U.S. are at risk of becoming threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act,” said Anthony Tur, the Service’s at-risk species conservation coordinator in the Northeast. That includes the Chesapeake logperch, which has been petitioned for listing.

But ‘at risk’ means there’s still time.

“If we act now, we can give these species a chance to rebound before they need federal protection,” Tur said.

This approach not only gives us more time to help species like the Chesapeake logperch but also focuses our expertise, science and resources for the greatest impact and return on investment.

Our at-risk species effort complements other priorities, including listing wildlife under the Endangered Species Act when necessary — a process that has saved many species from extinction.

We think of the at-risk species approach as preventative medicine. If we work with partners to keep these species healthy, we can reduce the likelihood they’ll become endangered. Some plants and animals may still end up in the conservation emergency room — protected by the Endangered Species Act — where they can recover with the right actions.

Starting with the highest priorities

In the Northeast, we used the best available science and input from Service biologists and state wildlife agencies to identify a set of priority at-risk species — such as Chesapeake logperch — and species groups — such as farmland pollinators — that offer the greatest opportunities for conservation success through proactive efforts.

The list of priorities will evolve over time as species’ statuses change — those that are doing well will be removed, and new ones that need attention will be added.

Different species have different needs. For some, like the Chesapeake logperch, we know how to help the species rebound. But others are poorly understood and need focused research to resolve unknowns, including the extent of their current range.

For example, the Appalachian grizzled skipper, a small, dusty-brown butterfly with white spots on its wings, was once found in isolated populations from New York to North Carolina, and west to Michigan and Ohio. At many sites where it was documented, this butterfly hasn’t been seen in more than a decade.

In 2020, the Service partnered with the U.S. Geological Survey and states to coordinate range-wide surveys to look for the Appalachian grizzled skipper across its historical range and document defining features of its habitat, so we can both assess the species’ status and know what it needs to persist.

Conservation in action

The Service is coordinating projects like these for a wide range of fish, wildlife and plants across the Northeast and the rest of the country, working with states, private partners, universities, and others, to support conservation on the ground where we know it’s needed, and to gather data when we don’t yet have enough information to act.

Are you in interested in collaborating with the Service to implement conservation or fill data gaps for at-risk species? Learn more about the Service’s at-risk species conservation initiative, including how to get involved.