Many visitors come to Leavenworth National Fish Hatchery to see fish, of course. At this time of year, there are more than 1.2 million young spring Chinook fingerlings in some of the outside raceways, and ready-to-spawn coho in Icicle Creek and the nearby adult ponds. But there are a lot of empty ponds too, as well as a huge constructed channel almost a mile long and often completely empty of water. Naturally, people have questions.

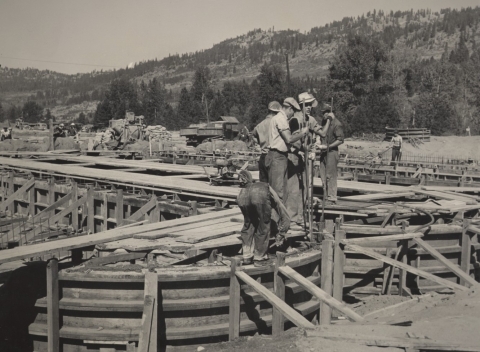

This hatchery was the largest in the world when it was built in 1940. (Where is the largest hatchery in the world today? Think hard... I'll share the answer later.) But it was no ordinary hatchery: the innovative plan at the time was to raise fish directly in Icicle Creek. A series of four dams divided the natural creek into ponds. Adult fish were expected to make their way into the ponds and spawn; and young fish were meant to spend their first year right there. A 4,085 foot-long diversion channel was constructed to control water flow into the now-modified natural creek.

The plan failed almost immediately. In summer, there was not enough water in Icicle Creek to flush out the fish waste and keep oxygen levels high. The temperature was just too warm for cold water fish like salmon. And predators found the plan much to their taste. Banks of ponds were installed at the hatchery instead.

But even these ponds were innovative. Called Foster-Lucas ponds for their inventors, the oval structures had automated brushes to clean up waste, as well as circulating water flow to help young fish develop muscle and maintain fitness. Three banks of 76 foot-long and four banks of 130 foot-long Foster-Lucas ponds were installed at the hatchery. But these proved problematic, especially when scaled up. In the large ponds, the rotating brushes simply swept fish waste into the water column, lowering oxygen levels and creating an unhealthy environment for the fish. None of the large ponds are in use today. Forty-five 8x80 foot rectangular raceways and fourteen 10x100 foot raceways replaced them. As for the smaller Foster-Lucas ponds, only some see seasonal use, and all are being phased out for better designs.

The diversion channel was built so it is higher at the downstream end than upstream. This was intentional, capturing water in the channel to help charge several adjacent hatchery wells. When water levels are low in summer, the channel stands empty as all the water in Icicle Creek is now allowed to flow unimpeded into the natural creek to support wild fish and other aquatic creatures.

The diversion channel may be dry now, but in spring and fall flood season, it is brim-full, gushing over a spillway into Icicle Creek. The sound of the waterfall draws salmon seeking their way upstream, but the spillway is too steep for a salmon to conquer. Instead, they may choose to leap up the fish ladder, or to follow the river farther upstream.

Leavenworth National Fish Hatchery raises 1.2 million spring Chinook salmon each year for release. This is fewer than we once generated, but for good reason. More is not always better. A lower number of fish means more room in the rearing raceways and healthier conditions. We keep them nearly two years to ensure they are the optimal size for surviving the journey past seven dams to the sea. These practices are based partly on research carried out by the Mid-Columbia Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office's monitoring and evaluation team, which advises our hatcheries. So while we're still big, we're not the biggest hatchery in the world any longer.

What hatchery holds that honor? I guessed perhaps one in China, where aquaculture has ancient roots (archeological evidence of it goes back some 8,000 years). But it is Anderson's Minnow Farm outside of Little Rock, Arkansas, that claims the title, counting by the number of fish. The history of aquaculture has many chapters. The role of our hatchery is significant enough to warrant being a National Historic Landmark National Historic Landmark

National Historic Landmark is a nationally significant historic place designated by the Secretary of the Interior because it possesses exceptional value in illustrating or interpreting the heritage of the United States. More than 2,600 places bear this designation, 10 of them on U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service lands.

Learn more about National Historic Landmark . Come for the fish, but the history might grab your attention, too.