Come hear a fish tale of epic scale. This is a story of the Bear River and the fish that call it home.

When We Last Left Our Hero

Bear River Cutthroat Trout, also referred to as the Bonneville Cutthroat Trout, depend on the Bear River.

A 2011-2014 radiotracking study conducted by Trout Unlimited found that migrating Bear River Cutthroat Trout had difficulty swimming over several barriers in Wyoming, such as the Evanston Dam. Another barrier blocking fish migration was the Almy Ditch, a section of the Bear River downstream from Evanston, WY. Almy Ditch is the setting of this “tail.”

Of the fish passage fish passage

Fish passage is the ability of fish or other aquatic species to move freely throughout their life to find food, reproduce, and complete their natural migration cycles. Millions of barriers to fish passage across the country are fragmenting habitat and leading to species declines. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's National Fish Passage Program is working to reconnect watersheds to benefit both wildlife and people.

Learn more about fish passage barriers, Jim DeRito, the Bear River Project Manager for Trout Unlimited said, “Radio-tagged cutthroat trout in the Bear River moved from downriver of Evanston, like the Almy Ditch area, all the way to the Uinta Mountains for spawning in the spring. These migrations were upwards of 40 miles in one direction and demonstrated the need to improve fish passage across the Bear River.”

At Almy Ditch, several perils were limiting passage of the mountaineering Bear River Cutthroat Trout and their merry band of traveling fish friends like the bluehead sucker, mountain whitefish, mountain sucker, red-side shiner, and speckled dace.

An Out of Control River

Rivers move like a fish, whose head and tail work in undulating patterns to slowly swim back and forth across the landscape. Time, gravity, moving water, and sediment erosion form the curving path.

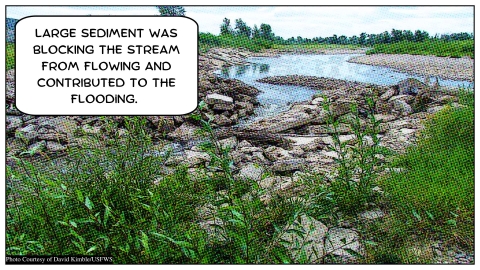

However, at Almy Ditch, the Bear River was out of control. The river widened by 25 feet over 25 years (1994-2019). The banks were continually washed out and were unable to sustain long-term plant growth. Under the water’s surface, excessive sediment had flattened the river bottom and filled in deep pools – a critical habitat feature for the cold-loving Bear River Cutthroat Trout.

The wide banks of the Bear River were also affecting the landowners who neighbor Almy Ditch. Stewart Hayduk is a third-generation landowner who has lived and raised cattle next to Almy Ditch for 43 years.

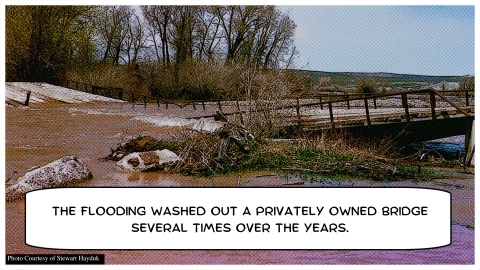

Since Hayduk was a child, Almy Ditch has been flooding. To his memory, the Bear River washed away a bridge on the property twice (in 1952 and 1983) and “took out the [cattle] fence 3 times in 15 years.”

There are several causes for the floods at Almy Ditch. Historically, as Evanston grew as a city, various projects straightened the Bear River and raised its banks. These alterations caused the speed of waterflow to increase in certain areas.

Hayduk said, “There is no control of the water upstream. When snowmelt happens and the water rushes down, there’s no slowing it. It shoots out like a firehose.”

When water moves at high speeds it erodes riverbanks at a faster rate and can lead to a large buildup of sediment. According to Kerri Sabey, District Manager for the Uinta County Conservation District, excessive sediment “causes rapid channel migration [widening and shifting of the river channel] and severe bank erosion, further increasing sediment loads.”

A Perilous Climb

Rivers have a superpower known as “stream power.” Stream power refers to the combined forces of speed, volume, and downhill gradient of the water moving through a waterway. Adequate stream power allows rivers to move sediment to keep waters clear, cool, and habitable for fish such as the Bear River Cutthroat Trout.

Fish aren’t the only ones who call the Bear River home.

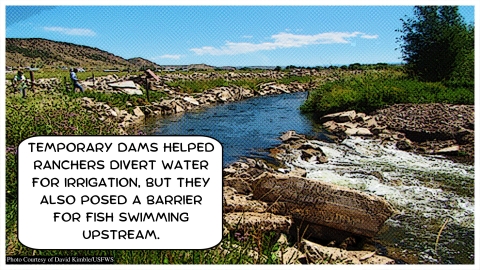

Adjacent landowners rely on the Almy Ditch to provide water for irrigation. The landowners diverted water to their lands by constructing stone and cobble pushup dams in the stream channel. However, pushup dams alter the shape of river, put immovable boulders into the stream, and send excessive smaller debris downstream.

These obstructions can also form barriers for fish such as the Bear River Cutthroat Trout. Even a courageous leap by an intrepid cutthroat trout may be insufficient to clear these peaks.

A League of Superheroes

A league of superheroes came together to address the challenges at the Almy Ditch, aiming to improve the site for fish, wildlife, and people by achieving four main goals:

- stabilizing the river,

- improving water quality,

- improving fish passage, and

- restoring wildlife habitat.

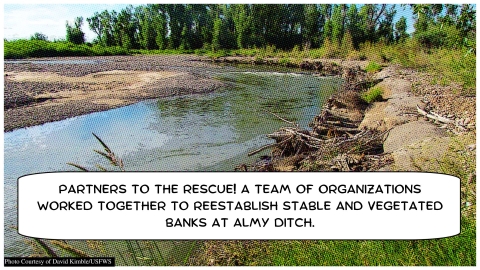

Through tireless effort from the partners, the Almy Ditch project was completed in the fall of 2021.

The project removed the irrigation pushup dam and “restored 1,975 feet of the Bear River”, said David Kimble, biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Partners for Fish & Wildlife Program. The banks are now secured with root balls called toewood, which also provide cool hiding places for resting fish.

Kerri Sabey summarized the benefits of the Almy Ditch project to the wildlife and to landowners as “a more stable river with less sediment and much improved water quality and habitat.”

For the Good of All Fish-kind

The restored river’s curves will help control the speed of the water, prevent major washouts, and allow the banks to develop a stabilizing and shade-providing plant community again. The goal was not “to create a river channel that never moves, but to create a channel that moves at rates consistent with naturally stable rivers of this type,” said Sabey.

Moreover, a stable river will allow landowners to install permanent fencing and other structures on their neighboring lands, without fear of floods washing them away.

Stewart Hayduk remarked, “I was skeptical about some of the methods, but it has worked out very well. It has protected the banks and the bridge, even during continuous high water.”

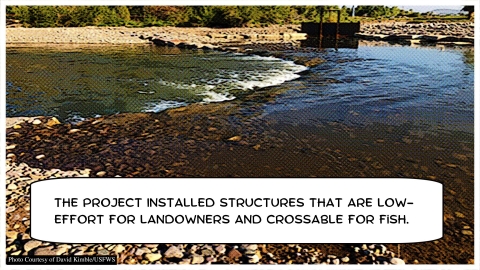

Instream structures called rock-cross vanes allow irrigation water to be diverted without the need for push-up dams. These structures save landowners time and resources, while also allowing fish to pass.

The adventuring Bear River Cutthroat Trout can traverse these heights and continue upstream on their journey to scale the mountains and reach their spawning grounds.

A United Tomorrow

Stewart Hayduk has seen numerous benefits that this project brought to his ranch, and he “hopes [the restoration projects] continue up ‘til town.”

“Stream restoration projects of this size and scope are no small undertaking,” noted Sabey. “They would not be possible without the collaboration and cooperation of many different partners including landowners, private organizations, government agencies, and experienced engineers and contractors.”

Partnering organizations will be working together to monitor the impacts of the project both upstream and downstream. Uinta County Conservation District will be monitoring water quality, Wyoming Game and Fish Department will survey for fish abundance, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service will be tracking changes to river channel size overtime.

For now, Hayduk says he’s not an angler, but “a pair of bald eagles have been nesting nearby for 25 years, so the fishing must be good.”