500,000 Years Ago Canada Goose Ancestors Blew off Course

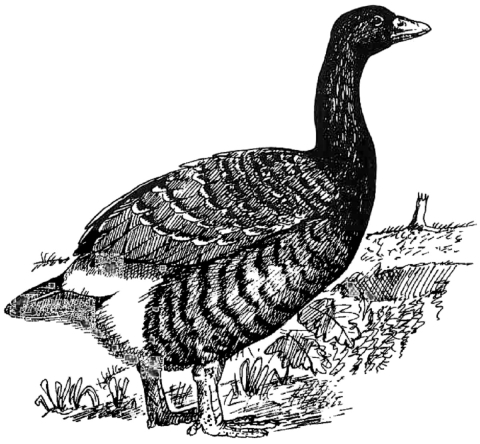

Before Polynesians settled Hawai‘i over a millennia ago, three unique species of geese thrived in Hawai‘i— nēnē (Branta sandvicensi), nēnē nui (Branta hylobadistes), and the giant nēnē (Branta rhuax). All three were descendants of Canada goose ancestors, which arrived in Hawai‘i approximately 500,000 years ago.

Little is known about the prehistoric giant nēnē but fossil records show that the nēnē nui went extinct shortly after humans settled the islands. Humans hunted them for food and brought in predators including rats and dogs who preyed on the birds and their eggs.

The faster and more agile nēnē escaped the tragic fate of their larger cousins.

Even in the early 19th century they still flourished on nearly all the Hawaiian Islands. On Hawai‘i Island alone there were an estimated 25,000 nēnē!

A New Wave of Threats Arrived

Europeans arrived in the late 18th century. Nēnē were hunted to feed whaling ships and new settlers. During the plantation era in the 19th and 20th centuries huge swaths of habitat were destroyed and more predators including mongoose were introduced. By 1950 the nēnē population had collapsed with less than 30 nēnē estimated to be living in the wild, all on Hawai‘i Island.

Captive-breeding programs breed nēnē from private collections in Europe, Hawai‘i and the mainland United States in effort to recover the nēnē population. Between 1960 and 1997 over 2,000 nēnē were released on Hawai‘i and Maui. Reintroduction efforts were met with mixed results. Introduced predators, especially mongoose killed many of the newly released nēnē and their offspring.

Kaua‘i Held off on Reintroduction

Conservation biologists did not immediately reintroduce nēnē to Kaua‘i because there was no known history of nēnē nesting on the island. That was until research at Makauwahi Cave Reserve on the south shore of the island exposed deeply buried nēnē bones. The discovery finally provided the necessary evidence to begin planning for reintroduction on Kaua‘i.

The first release of a dozen young captive-reared birds took place at Kīlauea Point National Wildlife Refuge in 1991. Reintroduction efforts continued through 2000.

A Conservation Success Story

With no established mongoose population, nēnē thrived on Kaua‘i and helped bring up the state population numbers. By 2012 Kaua‘i accounted for an estimated 60% of Hawaii’s statewide nēnē population.

In 2019 the nēnē population was estimated at 3,252 and the species was Federally down-listed from endangered to threatened. While this did remove some of the protections guaranteed by the Endangered Species Act, conservation efforts continue throughout Hawai‘i and Kaua‘i. Kīlauea Point National Wildlife Refuge leads several of those efforts.

The 2022 annual nēnē population survey estimated 3,862 statewide with 2,430 of those birds on Kaua‘i.