Townsend, Georgia – The virus spread through cities large and small, overwhelming hospitals, shuttering businesses, and killing thousands. It originated, supposedly, overseas and quickly jumped from country to country. Not until the federal government imposed mandatory quarantines and jump-started the search for a cure did the pandemic release its grip on the nation.

It wasn’t Covid-19. It was yellow fever, the epidemic of 1878 that killed more than 20,000 people across the South and prompted a federal response that ultimately relegated the contagion to the history books.

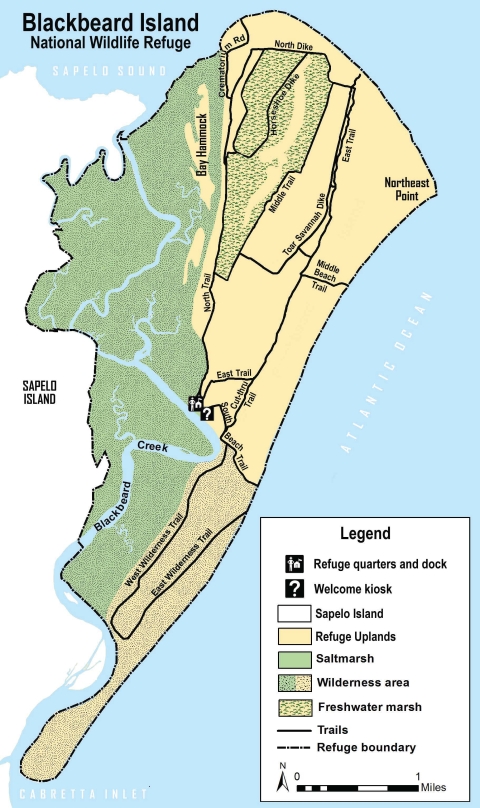

Nowhere was the threat, and response, more critical than today’s Blackbeard Island National Wildlife Refuge. Back then, the barrier island below Savannah was turned into a quarantine site with two lazarettos, or pandemic hospitals, and a fumigation wharf to rid in-bound ships and sailors of the possible virus.

A red-brick crematorium for disposal of infected bodies is all that remains on the uninhabited island. Nobody knows if it was ever used. But it serves as a forlorn, yet poignant testament to the government’s ability to respond to a crisis – then and now.

“You can see the government’s impact, and how they tried to reach out and help their fellow citizens,” said Russ Webb, who manages Blackbeard Island for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service). “All for the right reasons.”

‘A terrible year’

The South, Savannah in particular, is no stranger to yellow fever. Hot, semi-tropical climes offer perfect breeding grounds for Aedes aegypti, the mosquito responsible for killing millions, mostly in Africa. Slaves brought the virus to the Western Hemisphere with the first epidemic reported in the Yucatan Peninsula in 1648. Outbreaks occurred frequently in coastal U.S. cities over the next 250 years.

“We know about the Savannah epidemic of 1820,” said Jamie Credle who, along with husband Raleigh Marcell, runs the Davenport House Museum in Savannah which annually produces a dramatic recreation of the yellow fever epidemic that ravaged the city two centuries ago. (Covid canceled the 2020 production.)

“1820 was a terrible year,” Credle continued. “One day in August it rained like 10 inches. The first victims were in the Washington ward, a poor part of town. It just started to roll across the city from there.”

Yellow fever was a scary, deadly mystery. Nobody knew what caused it. Most surmised it came from a miasma of foul air brought on by rotting organic matter found in swamps and fetid wetlands. They knew the symptoms, though: chills, fever, back pains, jaundice (the skins turns a yellow-green tint), and uncontrollable hemorrhaging of fluids from the mouth and nose. Death typically came within a week. Roughly 60 percent of the infected died.

Officially, 666 people perished from the plague in 1820 in Savannah, then a city of 7,500 residents. Credle said if African-Americans had been counted the death tally would’ve been higher, closer to 900 people.

“You wonder how a little town like this could handle that sort of carnage,” Credle, the museum’s director, said.

Another yellow-fever pandemic struck Savannah in 1854, killing 1,040. And another in 1876 (1,066 dead). Many of Savannah’s doctors, according to the Georgia Historical Society, blamed the local climate and sanitary conditions around town. Others believed the ships and sailors debarking at the ports of Savannah, Brunswick and Darien introduced the disease from overseas.

Finally, two years later, after a pandemic ravaged the port town of New Orleans before heading upriver to Memphis, Congress created a National Board of Health. One of its first acts: opening the South Atlantic Quarantine Station on Blackbeard Island.

Fighting an ‘enemy’

Blackbeard was an obvious choice for a maritime hospital. It was isolated and unpopulated, yet close enough to Sapelo Island for food and the daily mail. Ships could anchor off the island’s north end. The south end, site of the hospital and living quarters, was free of standing water. And, most important, the federal government already owned Blackbeard.

The island was named for Blackbeard the pirate who, supposedly, availed himself of the region’s meandering creeks and hidden harbors in the early 1700s. Legend has it that Edward Teach, the infamous freebooter, buried plundered treasure among the sandy ridges and live oak forests of the eight-mile-long island. None has ever been found.

In 1800, the U.S. Navy Department paid $15,000 for Blackbeard at public auction. Shipbuilders coveted the island’s gnarled, yet sturdy, live oaks as hulls for warships. Post-Civil War, as the timber industry across Georgia rebounded in force, Blackbeard took on evermore importance.

“Yellow fever should be dealt with as an enemy which imperils life and cripples commerce and industry,” said Surgeon General John Woodworth, a year after the plague ravaged the lower Mississippi River Valley.

All ships enroute to ports between Savannah and St. Augustine, Florida were required to drop anchor at Blackbeard’s northern end for a yellow fever inspection and, if necessary, fumigation. A boarding station, with quarters for a policeman, and a “disinfecting apartment” – where the sulfurous gas was stored – stood along the north shore, according to an account at the time in the Savannah Morning News. Ships were disinfected twice.

Passengers and crew were escorted from the ship, placed into the steam launch Gypsy, and ferried to the island’s south end. The sickly entered the hospital. The hale, quartered separately, were checked twice daily for yellow fever and malaria. Buddy Sullivan, who wrote Blackbeard Island, A History, labeled as “awkward” the logistics of ferrying people from one end of the island to the other. The hospital was eventually moved to the north end.

Most of the ships quarantined at Blackbeard hailed from the Caribbean or South America – yellow fever hot spots. In 1891, for example, 28 vessels that alighted from “infected ports” were inspected at Blackbeard. Yet only one case of yellow fever was treated at the lazaretto, according to the Surgeon General. The following year, 35 vessels that departed from Havana, Rio de Janeiro or Barbados were detained. Indeed, 52 mariners had died prior to leaving those ports. Yet none of the ships required disinfection at Blackbeard.

1895 was a busy year on the barrier island: 90 ships were temporarily detained; 31 required the sulfurous spray.

“The importance (of Blackbeard) to the south Atlantic states, and even the entire country, cannot be over-estimated,” the Surgeon General reported in 1892. “It is the best-equipped station along the Atlantic coast, as it is believed there are more infected vessels sent to this station, and are treated at this station, than at any other on this coast.”

The annual reports detail everything from number of employees (23) to buildings (13) to wharf frontage (250 feet), yet they don’t list how many patients were treated or died. Neither does Buddy Sullivan. It’s unclear whether the crematorium, built in 1904, was ever used (although Clemson University researchers hinted that it was). By then, though, the scourge of yellow fever had passed. U.S. Army pathologist and bacteriologist Walter Reed, and members of his Yellow Fever Commission, had proved that the disease was transmitted by the bite of a mosquito and not by foul water or rotting vegetation. A vaccine was all that was needed to defeat yellow fever.

Lessons for today

The South Atlantic’s largest marine quarantine station was deactivated in 1909. The remaining buildings were dismantled and sold for scrap. President Woodrow Wilson signed an executive order in 1914 turning Blackbeard Island into a wildlife preserve for the protection of migratory birds. It became a national wildlife refuge national wildlife refuge

A national wildlife refuge is typically a contiguous area of land and water managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for the conservation and, where appropriate, restoration of fish, wildlife and plant resources and their habitats for the benefit of present and future generations of Americans.

Learn more about national wildlife refuge in 1940. Today, nearly half of the island is designated as National Wilderness, destined to remain in a natural, untrammeled state forever. All that remains of the quarantine era, amid the salt and freshwater marshes, the endless beaches and the maritime forests, are some old water and sewer lines and ballast piles off the north end.

And the crematorium, of course.

“This is it,” Webb said as he crunched along a carpet of live oak leaves on Crematorium Road. “This is what’s left.”

The 12-foot-long brick furnace, with iron doors on either end, remains in good shape with some bricks crumbling and ferns jutting from the roof. It sits 15 feet above sea level on a sandy ridge affording a lovely view of dunes and swales leading to the ocean. A chimney rises alongside the tapered kiln. Bits of coal lie about.

Webb says the crematory should be preserved as a reminder of the government’s role in response to a national emergency. Maybe, he says, lessons learned from a previous pandemic offer guidance for today’s pandemic.

John Tone agrees. He’s a history professor at Georgia Tech who’s writing a book on the history of yellow fever. While he credits the Marine Health Service for establishing the quarantine station on Blackbeard, he rightly notes that real progress against yellow fever didn’t come until 1900 when Walter Reed and colleagues corroborated research that showed infected mosquitoes, not miasma, caused the disease. The federal government then mobilized the U.S. Army and other departments to rid infected areas of standing water. After a vaccine was created in 1937, the government undertook vaccination campaigns and provided money to states for inoculation. Today, states also require school children to be vaccinated against a wide variety of diseases, including diphtheria, pertussis and meningitis.

“The federal government has to step up and do whatever it takes to get vaccines in peoples’ bodies,” Tone said. “We do require vaccines for kids to be able to go to school or to travel abroad to certain places. It’s not unprecedented to require vaccination.”

Credle, the museum director, says the Covid pandemic, yet again raging across the country, requires a federal response.

“Who do we look to for help in a time of need? Who do we look to alleviate so much suffering?” she asked. “Now, for better or worse, we look to the federal government. We need to follow the science as best we can. What else are we going to do?”