Richard J. Guadagno was the 38-year-old manager at Humboldt Bay National Wildlife Refuge in California when he died on September 11, 2001. He and 39 other passengers and crew were aboard United Flight 93 when the hijacked plane bound for San Francisco from Newark, New Jersey, crashed near Shanksville, Pennsylvania.

Guadagno was one of almost 3,000 Americans to die at the hands of terrorists that day.

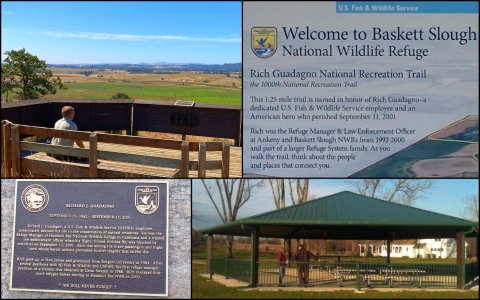

In his 17-year career with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Guadagno worked at several wildlife refuges. He began as a temporary biologist at Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge in New Jersey. His first permanent Fish and Wildlife Service job was as a wildlife inspector in Philadelphia. Subsequent career moves took him to Prime Hook National Wildlife Refuge in Delaware, Supawna Meadows National Wildlife Refuge in New Jersey, Baskett Slough and Ankeny National Wildlife Refuges in Oregon and, in 2000, to Humboldt Bay National Wildlife Refuge.

We asked a few Fish and Wildlife Service employees who knew him to help us remember and honor their friend and colleague.

On September 11, 2001, Shannon Smith, then 28, was one month into her new job as deputy manager at Humboldt Bay National Wildlife Refuge. She recalls the last time she saw Guadagno. It was just days before he flew east to celebrate his grandmother’s 100th birthday. Smith, Guadagno and a colleague were considering how best to restore a refuge wetland. “So, rather than rush the decision, I suggested we all think about the ideas discussed and come back together after he returned from vacation . . .” Smith says, her voice trailing off.

Smith recalls Guadagno’s kindness, his leadership and his passion for conservation.

In June 2001, before she had been offered the deputy job, she was in town visiting friends. “I made a point to meet with Rich and see how much the refuge had changed since I worked there as a student intern six years prior,” she says. “He spent four hours of his busy day showing me the transformations. I came away with a clear vision of what Rich saw for the refuge’s future. I left inspired and hopeful to be a part of the team.”

Paula Golightly managed the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program and the Coastal Program in nearby Arcata, California. She periodically met with Guadagno. In September 2001, she says, “I went to visit him to see how the new visitor center was coming along and to talk about the latest regarding restoration project funding and partners. We talked about what a great view of the wetlands his new office was going to have. He left for the East Coast a couple of days later, and I never saw him again.”

Golightly remembers that Guadagno “believed in being inclusive and wanted to spark more in-depth interest from the public in fish and wildlife while also protecting and restoring habitats.”

Eric Nelson, who worked closely with Guadagno for several years, succeeded him as manager at Humboldt Bay National Wildlife Refuge.

“Rich had many challenges at Humboldt Bay — small budget, short-staffed, a major clean-up and getting a new office built,” says Nelson. “But, in my mind, he recognized and focused on the most important job, the restoration of Salmon Creek, which is the heart of the refuge. He immediately began pulling together the necessary partners to get that project started.”

Nelson continues: “Rich was determined to do what was right and needed for the resource. He could and did enjoy the special moments our career choice afforded us. But, as with so many in the Fish and Wildlife Service, his career was a calling. He sure as hell wasn’t going to shortchange it — and he didn’t.”

Dave Paullin was Guadagno’s supervisor on September 11, 2001. He recalls that Guadagno wanted Humboldt Bay National Wildlife Refuge’s new visitor center to be perfect. In that regard, Paullin says, “he was doing an outstanding job. In this case, poignancy surfaced on two fronts. First, the contractor completed his final punch list while Rich was in New Jersey, so he never got to sign off on it or see the finished project. Second, the completed building was ultimately named for Rich by an act of Congress.”

Both supervisor Paullin and deputy Smith describe Guadagno as being a Renaissance man.

“Some Fish and Wildlife Service folks are ‘waterfowl guys’ or ‘fish guys,’ but Rich’s conservation ethic and interests covered a broad spectrum,” explains Paullin. “He collected rocks, seashells, loved wildlife and studied the stars with his telescope. He grew orchids, did bonsai plants and was a gourmet cook. His interests in the natural world and the outdoors were without limits.”

Rob Larrañaga remembers Guadagno as a talented, dedicated colleague who strived for the best. “One could possibly say he was a perfectionist,” Larrañaga says. “It disappointed him when things were not in the best of order.”

Larrañaga and Guadagno were brothers in conservation. Each man was a refuge manager and a law enforcement officer. Each was committed to enforcing the laws that protect public lands and wildlife. Each was a graduate of the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center. The two men trained together. They spotted each other on the bench press. They groused about professional frustrations, large and small. Each dreamed of buying land in New Mexico, something Larrañaga has since done.

Guadagno was the only federal law enforcement officer aboard any of the four hijacked flights on 9/11.

In 2010, Jim Hall, then the National Wildlife Refuge System’s law enforcement chief, presented an American flag to Guadagno’s father, Jerry, at the dedication ceremony of Pennsylvania State Game Lands 93, next to the eventual Flight 93 National Memorial.

“It was one of the most humbling, yet proud, moments of my career,” says Hall. “Afterwards, Jerry told me that he had been to several such ceremonies in the 10 years since Rich’s death, but that one was special because we were Rich’s co-workers and friends, his working family.”