The elders of the small Inupiaq village of Point Lay in the northwest reaches of Alaska remember a time when the Arctic sea ice and the animals that depend on it followed reliable patterns. In particular, they tell of a time when only a handful of Pacific walruses visited the shores of the barrier island beyond their community.

What was once true is no longer. Thousands of Pacific walruses now show up, raising concerns and sparking a community-wide effort to help the massive marine mammal survive in a dramatically changing climate.

Changing Climate

“When the walrus first started coming to shore, it was kind of strange to us that they were all beaching on the shore,” Leo Ferreira III, former Tribal council president, said in 2016. “Then we just realized that there is no ice and that is why they’re coming to shore.”

And the walruses aren’t the only rapid changes in the environment. The permafrost is melting, causing the ground to sink. The houses, which are built on piles, now balance precariously high above the tundra with large pools of water on the ground below during the summer months. People see birds and insects they have not seen before, and the timing of migrations is shifting.

Changes to wildlife can be especially hard for the citizens of Point Lay. They depend on foods collected from the land and sea.

“You know food gathering, that’s how we live. We learned it from our ancestors. It’s our culture,” resident Allen Upicksoun said in a 2017 interview. “Your body is designed to eat certain foods, and when you don’t eat them, it’s like you’re missing something, you know?”

The people of Point Lay also have a deep respect for and spiritual connection to the Earth and the animals they live with and from.

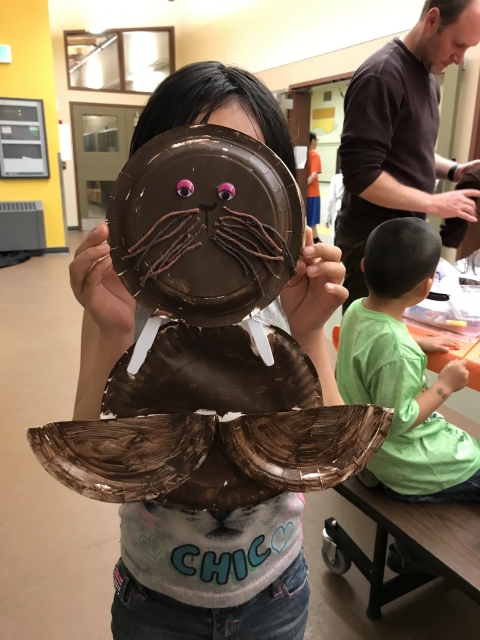

At traditional drumming and dancing practices, each song and dance tells a story about the animals, hunting, fishing, or gathering. One song called Walrus ends with the children making the sounds of walruses with their pointer fingers hanging down from their mouths.

The walrus is also a way of life for some Point Lay residents, such as ivory carver Ira Itta.

And so it was that the unusual arrival of the big visitors prompted a partnership that includes the Service—an effort designed to protect the seagoing mammals and their young while on shore. These efforts include monitoring and working to prevent human-caused disturbances.

Since 2007, say biologists, walrus female and their calves have been leaving the Chukchi Sea and coming ashore on the barrier island near Point Lay, a village 700 miles northwest of Anchorage on Alaska’s North Slope. They show up in late summer or early fall—a response, scientists say, like Ferreira, to the loss of sea ice. Biologists call these groups of walruses on land haulouts.

This is a marked change in behavior. Traditionally, mothers and their young left the Chukchi’s depths to rest on sea ice. Walruses are better suited to life on the ice instead of land, as they can slip easily back into the sea to forage or avoid predators.

Danger

On land, the creatures are skittish: a sight, sound or odor can cause the walruses to panic and flee to the sea for safety. When large numbers of animals do this, it is called a stampede. The animals—particularly the yearlings and calves—can get injured or killed.

Thousands of walruses now come to the barrier island just north of Point Lay, says Jim MacCracken, a supervisory wildlife biologist with the Service. “The site has been occupied by as many as 40,000 animals at its peak,” he says.

Aircraft overflights are particularly concerning. “We noticed that during that time the airplane traffic was causing stampedes,” Ferreira said. “I witnessed it with my own eyes.”

The Service and village contact local air carriers directly and work with the Federal Aviation Administration to let pilots know when the animals have hauled out and provide guidelines.

Walruses aren’t the only seasonal visitors to Point Lay. The arrival of the large mammals draws reporters and other curious people, too. That’s not surprising. The creatures are immense—a male walrus weighs about the same as a Toyota RAV-4, about 3,700 pounds.

But Point Lay does not have the infrastructure to host the two-legged visitors: there are no restaurants, and the only lodging in town closed in 2016.

To help people understand why it isn’t a good idea to attempt an in-person visit to see the walruses, the Service and the tribe have worked with the nonprofit Alaska Teen Media Institute to develop short educational videos. Youth at the local school, with training and support of the institute, interviewed elders and one another for the videos.

Point Lay and the Service have a common goal: to keep walruses around for future generations.

In Point Lay, people are guided by their traditional value of respecting the earth and all that it provides for future generations. The Service and the tribe will continue to work together to keep the walruses safe while on shore.

“We can prevent walrus disturbance and many trampling deaths,” Ferreira said, “but everyone needs to listen and pay attention to help the walrus.”

- This article is from the summer issue of Fish & Wildlife News, our quarterly magazine.

- More Fish and Wildlife News, including how to subscribe to our Fish and Wildlife News email list.