She wanted to work with people – be a nurse, maybe even a doctor.

Then, a college course about salmon – in the wild, not on the plate – changed Kimberly True’s life.

The future of the 1980s college student took a hard turn, abandoning a potential career in human health to pursue one devoted to raising healthier fish.

“I got really excited about them and thought they were amazing creatures,” she said, describing the salmon’s lengthy trek to the ocean and its marathon return riddled with obstacles. “They really work very hard to survive.”

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service scooped her up after she finished her biochemistry degree, assigning her to one of the agency’s fish health centers in the Pacific Northwest. The 30-year career that followed has focused on support and diagnostics for federal hatcheries raising and releasing salmon and other fish in California, Nevada and Washington.

What didn’t change was her commitment to patients: fins or legs, she would advocate and ensure they received the best care. True’s a self-proclaimed quality control and quality assurance geek, because to her it’s all about good science.

Think of her as part health inspector, part vet. True and her lab colleagues detect, prevent and control infectious diseases. They peer through microscopes at cells, tissues, and organs, and identify and culture bacteria, viruses, and fish parasites. Then they advise hatcheries regarding sanitation, disinfection and fish treatments.

“It does make a big difference to keep the fish healthy,” said True, who’s the assistant center director after working at the California-Nevada Fish Health Center for 22 years. “All those resources produce a fit, strong fish that has higher potential for survival versus a weak, sickly fish. They’re up to the task of what they need to do — migrate to the ocean, survive for two to three years, and then migrate all the way back.”

True, along with retired fish veterinarian Chris Wilson, sits on an American Fisheries Society committee dedicated to quality management. The society recently finalized an extensive program for quality assurance and quality control in aquatic animal laboratories.

“It is critical for hatchery managers and people in the state or region to know that whatever the result is from that lab is the most accurate that it can be,” said Wilson, who worked for the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources and is past president of the society’s Fish Health Section.

The stakes can be high, he noted.

“One glowing bacteria under the microscope… can shut down a whole hatchery or fisheries management program,” Wilson said. The discovery of some pathogens can even mean a hatchery’s fish must be destroyed, he said.

For years in the 1990s, Coleman National Fish Hatchery in Anderson, California, annually lost thousands of fall Chinook salmon to an infectious viral disease. They are one of numerous stocks of Chinook salmon along the West Coast, some of which are listed as threatened or endangered.

The symptoms were impossible to miss, but common of many illnesses: bulging eyes and stomachs. Lethargy with periodic frenzied swimming. Darkened skin.

“It was really sad to see,” True said. “We’d grow them, and they’d get a month or two old, and they’d die of this virus.”

“We’d lose so many of them, and it felt like there was nothing we could do about it.”

The California-Nevada Fish Health Center experts stepped in to help the hatchery find a solution. They identified the virus, infectious haematopoietic necrosis, or IHN.

There was no cure.

But they knew the source: adult salmon were exposed to the disease outside the hatchery. When the adults returned to spawning grounds above the hatchery, those fish infected the water supply. That, in turn, exposed thousands of the hatchery’s juvenile salmon to the virus each year.

Managers, technicians and hatchery staff found a long-term solution, installing an ozone plant at the hatchery. The plant disinfects the water before it makes its way to the fish. It’s similar to how municipalities treat drinking water. When ozone makes contact with contaminants and pathogens, it virtually grabs and eliminates them, making the water clean and safe again. The system processes enough water to fill a standard swimming pool in one minute.

The results? “We haven’t had IHN virus ever since,” True said.

In the decades following, Coleman has annually produced an average of 12 million healthy fall Chinook salmon.

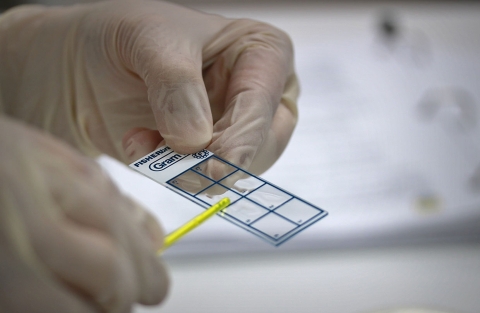

Infectious haematopoietic necrosis can pass from fish to fish through water or contact, and, without proper disinfection, it can also go from a parent to its eggs. So can bacterial kidney disease, which also has no effective treatment. In college, True was an early adopter of a technique called enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, which helps efficiently separate fish with this kidney disease from healthy fish, a key step in minimizing the spread.

One of her responsibilities now is to make sure the endangered winter-run Chinook salmon that return as broodstock broodstock

The reproductively mature adults in a population that breed (or spawn) and produce more individuals (offspring or progeny).

Learn more about broodstock to the Livingston Stone National Fish Hatchery in Shasta Lake, California, do not transmit this disease.

Bacterial kidney disease is fairly common in salmon, but it can cause health problems and die-offs. The risks are much higher in captivity. The unnatural tank environment, along with other elements of captivity, can chronically stress salmon, making them much more vulnerable to the disease.

“It’s important that our lab tests can detect these pathogens,” said True. If they find a female with a high level of this pathogen, they can remove her before she infects other fish, and treat her eggs to avoid spreading the disease among juvenile fish.”

Keeping the young fish clean and healthy is a critical investment, as they’ll stay at the hatchery for three years before they mature and produce the next generation of salmon. This year, Livingston sent 210,000 Chinook salmon to Coleman hatchery to be released in Battle Creek, an important tributary, and they will supply 230,000 winter-run Chinook salmon for release into the Sacramento River.

A key resource for fish health professionals has been the American Fisheries Society’s Fish Health Section Blue Book, a handbook for the detection and diagnosis of aquatic animal diseases. Readers can browse page-size images of fish lice or skim steps to isolate and culture diseases like Piscirickettsiosis or Motile Aeromonas septicemia.

The handbook was written as a resource for labs of all sizes and specialties, so the society’s new process requires labs to step those procedures down to their needs.

Over a year and a half, the lab codified their detection techniques in nearly 60 standard operating procedures, ranging from how to make, read and freeze a viral plate to how to extract and test sick fish for small amounts of a bacteria or virus DNA.

About a dozen federal, state and tribal labs have achieved the first tier of the laboratory recognition. That includes the Service’s other fish health centers in Montana, New Mexico, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

This program is designed for small to medium-sized laboratories, in lieu of other options like the American Association of Veterinary Laboratory Diagnosticians accreditation program.

“The requirements for going through those other processes are very intensive in terms of people, money and other resources,” said Wilson, the retired fish veterinarian. “It’s beyond the capacity for small fish health laboratories throughout the country. That’s why we have designed a similar program that can be achieved over time in incremental steps.”

Dr. Joel Bader, the Service’s national coordinator for aquatic animal health, aquaculture and technology, said accreditation lends scientific and forensic credibility to their work. He points to Kimberly as a leading force for the agency’s labs.

“She’s always been a leader in quality control and making sure we have standard operating procedures and that we follow sound scientific principles as we do our work,” Bader said.

In fact, True was the force behind establishing a network and standardized approach in 1998 to monitor and manage fish disease in the wild. At the time, a disease decimating trout in the Northwest was raising alarm across the country. The resulting National Wild Fish Health Survey is conducted by the agency’s labs along with other organizations, tribes and industry.

True is glad to see the Service excel in this changing field. “We’ve moved away from older microbiology methods like growing bacteria in a petri dish” to DNA research and other highly sensitive procedures that probe genes, she said.

Clear laboratory procedures are critical as workload increases, budgets decrease and the workforce shrinks. Reducing the likelihood of mistakes can save resources and time, too.

The next tier in the American Fisheries Society’s process was unveiled this month. It focuses on additional personnel training in quality management systems and includes internal audits of the fish health centers.

True would love to see the center go for it. In this regard, she’s no different than that college student who wanted to look after patients with legs, not fins.

“It’s about good science,” she said, “demonstrating that we have competency and expertise.”

And giving those fish the best chance at survival.