Cellular towers and migratory birds are typically a perilous combination. However, biologists are using the ‘superpowers’ of cellular towers for good when it comes to tracking endangered whooping cranes in the Aransas-Wood Buffalo population.

Ten juvenile whooping cranes were trapped and fitted with solar-powered Cellular Tracking Platforms (CTPs) in Wood Buffalo National Park in summer 2017. In January 2018, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and U.S. Geological Survey biologists trapped and banded 7 more birds on their wintering grounds at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. Key partners on the project include the U.S. Geological Service (Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center), Canadian Wildlife Service, and Parks Canada, with veterinary assistance from the Dallas Zoo and the International Crane Foundation.

Capturing and Banding the Whooping Cranes

Wildlife biologists are up before the sun to bait and set leg snares. One type of trap uses a single snare baited with corn and a remote activation system, while another trap is a series of attached leg snares that the cranes walk into and entangle themselves. As soon as the crane is caught in the trap, scientists rush to the bird, capture it and cover its head to lessen stress, and get to work.

When the crane is captured, biologists place a CTP on one leg and a unique combination of 3 colored bands on its other leg. A wildlife veterinarian then checks the heart rate, measures the wing chord (length of the wing), and weighs the bird. DNA (saliva) and blood samples are also taken to measure stress hormones, potential contaminants, and to sex the bird. All of that information is recorded, along with the bird’s CTP number and color band combination, so that it can be identified from a distance.

Once biologists have banded and collected data, the whooping crane is released.

What Can We Learn from Cellular Tracking?

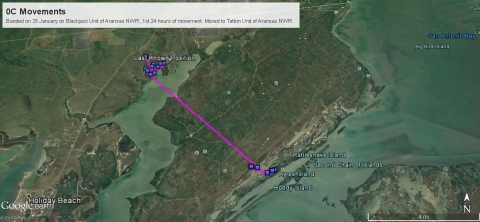

CTPs collect precise location data every half-hour, so 48 data points are collected each day. When the bird is within range of a cellular tower, location data points are transmitted to biologists.

As the wild whooping crane population continues to increase, biologists can use the information to track migration routes and habitat use on breeding and wintering grounds. The information collected on the wintering grounds will provide a better understanding of the specific habitat types preferred by whooping cranes, which will help the Service, and other agencies and landowners, better manage coastal prairies and wetlands for whooping cranes and other resident wildlife.