The great white bears that walk the land and sea ice of northeastern Alaska and northwestern Canada make up the southern Beaufort Sea subpopulation of polar bears in the circumpolar North. Indigenous peoples have lived here for thousands of years with Nanuuq, the Inupiaq name for the polar bear; traditional knowledge holds great respect for the bear, in part for its clever adaptations to hunting and living on both sea and land and surviving in difficult conditions.

The behavior and biology of the Beaufort Sea bears inspired the following story of a year in the life of a female polar bear along the coast of Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

. . .

It is early winter, and the Arctic Ocean is blanketed by a bumpy, jagged layer of ice. Here in the far north, the temperature remains well below freezing most of the year. In winter, the sun stays below the horizon for months at a time, and only the moonlight illuminates the snow-covered ice.

[A low sun barely clears the horizon over the Arctic coast, where cold, clear weather creates a “sun dog” halo of light above the frozen land.]

. . .

Several small holes in the ice dot this frozen landscape. Perched next to one of them is a massive polar bear. For hours she has been sitting at this very spot, still as a sculpture as she waits. In front of her giant white paws, dark water splashes against icy edges.

Nearby, she can smell the arctic fox that has taken to following her. The polar bear pays the fluffy white creature no attention. The fox is very quick, and always careful not to get too close. Trying to catch it would be a waste of her precious energy stores. Besides, it is so small it would hardly be a snack.

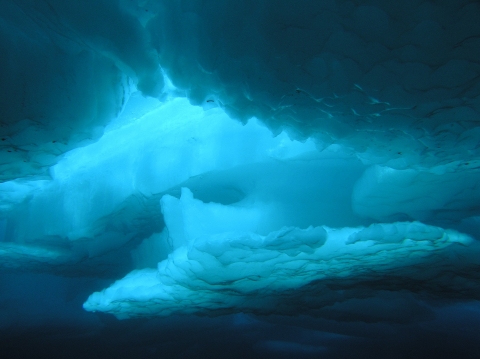

[The polar bear’s Latin name (Ursus maritimus) means “sea bear.” They spend much of their lives hunting seals on the sea ice. With their thick blubber, layered fur, and paddle-like paws, they are perfectly adapted to the icy waters of the Arctic.]

. . .

Polar bears need to eat a lot of fat to stay warm and survive the tough parts of the year. Ice seals, such as ringed and bearded seals, have a thick layer of blubber that make them excellent polar bear prey. Using their sharp claws, seals carve breathing holes in the sea ice. Though seals can stay underwater for a very long time, they eventually need to come up for air. Polar bears know this, and often hunt seals by ambushing them at breathing holes. However, one seal may use as many as twelve different holes in an area as it hunts for fish and crustaceans. If a bear picks the wrong hole, it may go hungry.

The polar bear’s muscles are stiff from sitting still for so many hours, but still she does not budge one inch. Her eyes remain fixed on the dark water.

Finally, a thin stream of bubbles floats to the water’s surface. A seal is near! The polar bear sits as still as the frozen world around her. These bubbles are the seal’s test. This bear has learned the hard way that if she falls for this trick and attacks before the seal is within reach, the seal will escape. Long moments pass as the seal waits underwater for a reaction from above. When the seal sees no sign of danger, it swims upward, preparing to take a deep breath.

Just as the whiskers break the surface, the polar bear plunges forward, sharp teeth and claws reaching for the seal. Snap! Her long jaws lock around the back of the seal’s neck. The bear uses her muscular hind legs to pull the seal out of the water, digging her claws into the ice. She drags the seal far from the water to prevent losing her prey.

. . .

The bear eats the seal’s blubber first. The fat will sustain her through the coming months. This polar bear is pregnant, and she will need a blubber layer of her own to survive the challenge of raising cubs. She will build a snow den to give birth. There, she will nurse her cubs through the winter, but for months eat nothing herself. The fat reserves she gains now must sustain her and her cubs until she can hunt again.

When she is done, she moves away and rubs her muzzle and paws against the white snow, cleaning and drying her fur so it will keep her warm. As soon as she steps away from the carcass, the arctic fox bounces forward to scavenge the remains. A good meal can be hard to come by during Arctic winters. By following the polar bear, this fox has guaranteed itself first access to the bear’s scraps. It lowers its head to eat, but keeps its eyes on the bear, in case she decides she’s not done eating after all.

. . .

But for now, her belly is full. Over the past few weeks, she has been hunting constantly, working to build up the fat reserves necessary to raise cubs. Now, she is ready. In a few hours, she will start her search for a suitable place to build a snow den. She must make sure the snow is deep enough to dig a bear-sized hole, and stable enough that it will not cave in on top of her. In the past, many polar bear mothers along the northern coast of Alaska built dens on the sea ice.

Nowadays, the warming climate has made it difficult to find quality places to den on the ice, so bears have increasingly been denning on land. As sea ice continues to shrink, coastal and river bluffs, barrier islands, and other areas where snow accumulates have become increasingly valuable for polar bears in this part of eastern Alaska.

Once she has carved out her den, she will enter and wait for snow to seal the entrance and block out the cold winter wind. Soon after, she will give birth and nurse her cubs until they are ready to return to the sea ice. First, though, it is time for a nap. She flops her enormous body down, resting her heavy head on a smooth lump of ice. As the moon sets above her, the green and pink lights of the aurora borealis start to dance.