“Did you know the bryozoans in the front pond aren’t native here?”

Biologist Ryan Munes struck his forehead with his palm in despair, only partly in fun. A multitude of non-native and invasive plants and animals crowd the sites that make up Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge Complex. Trying to combat them and make room for native species to thrive can sometimes feel like an overwhelming task, a lot like the Greek myth of pushing a boulder up a mountain over and over yet never reaching the top.

“Lucky for you these don’t appear to be much of a problem,” I told him. Pectinatella magnifica was first identified in the Pacific Northwest in 1998. It can travel in the guts of waterfowl, or with introduced fish or aquatic plants. It prefers the still waters of ponds and lakes, where it can join with others of its kind to create a strange, delicate colony.

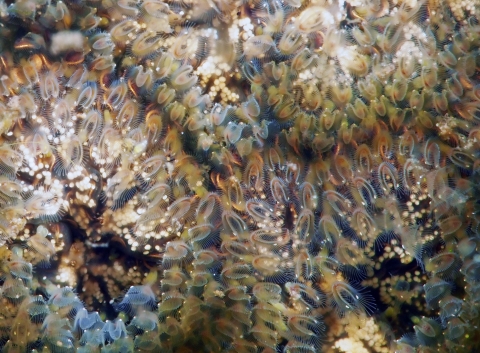

Bryozoans are tiny animals, no larger than 4 millimeters (5/32 of an inch) wide. They float alone for a time, but eventually form colonies, working together for mutual benefit. In this way, they are much like coral. But coral builds strong, sturdy structures that last long after the animals they house have died. Bryozoans also make structures from calcium carbonate, but far more fragile ones.

P. magnifica makes colonies attached to rocks or branches underwater. As the summer progresses, the colonies grow into large blobs that look like bouquets of sponges or translucent ghost flowers. Each animal (called a zooid, pronounced ZOH-id) feeds itself with a horseshoe of tentacles, filtering algae and diatoms from the water. They also take in clay and silt, so the clarity of the water in which they live improves. A single little zooid may filter as much as 8 milliliters (1/4 ounce) every day; and there are hundreds, even thousands, in a single colony.

The community of zooids has specialists, too. Some have long hairs that may keep the colony clean. Some brood eggs for reproduction. Some might hold the colony in place, clinging to a branch. And some may defend the colony from predators like fish by making pecking movements with a beak-like structure.

But the colony won’t survive winter. In the fall, small, hard statoblasts form into something like a seed, attaching to algae and other debris that sinks to the bottom of the pond. In spring, they float to the surface and produce lots of minute, free-swimming larvae. Within 24 hours, these settle and begin forming new colonies by cloning themselves.

Snails and some fish and aquatic insects eat P. magnifica. So do raccoons. But they are last-resort food for other animals. Humans don’t eat them, either. But they are food for thought, at least. Bryozoans have been on Earth at least 480 million years. Come lean over the rail in front of the visitor center in late summer and have a look at these weird and wonderful colonies.