What does outdoor access mean to you? Do you have a space nearby where you can enjoy hiking, fishing, birdwatching, hunting, or experiencing wide-open spaces? Not everyone does, and that is why we are committed to ensuring equal access to public lands through our Public Civil Rights Program.

What does lack of equal access look like? For someone in a wheelchair, it could mean staying in the parking lot while their friends are out on the hiking trails. For someone without transportation, connecting with wildlife may be limited to what’s in their neighborhood. Or, if there is a river nearby, is it even safe to play in?

Our Public Civil Rights Program is governed by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and other landmark laws that guarantee equal access to government services and facilities, along with other civil rights. These laws uphold the core tenant of Environmental Justice—that no community be negatively impacted, or disproportionately bear the consequences, of government actions.

We work closely with Service staff, state partners, national organizations, and other federal agencies to improve access to public lands.

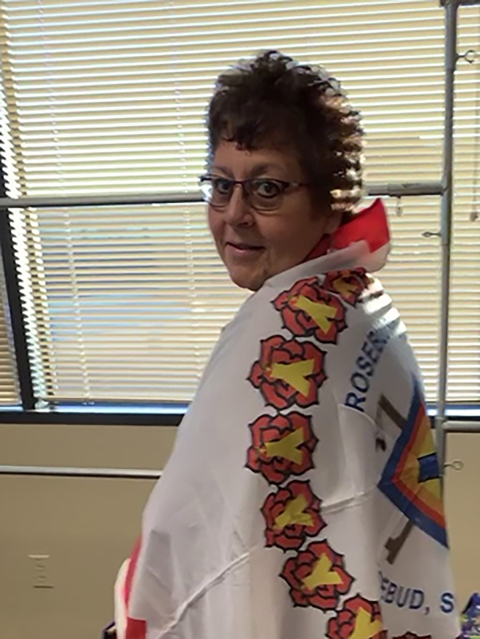

Bobbea Burnette Cadena assumed leadership of the program and the team of eight specialists earlier this year. For her, “managing the Public Civil Rights Program for the Service, to increase access, is a life-long desire.”

Ensuring access starts at home, so we regularly review our own programs, activities, and facilities to identify and remove any barriers that reduce or prevent access to the public areas we manage such as national wildlife refuges or national fish hatcheries. The team accomplishes this by working hand-in-hand with managers to provide access to boating, hunting, wildlife viewing, and other activities.

Equal access to public spaces, programs, and activities outside the agency is also important. We provide federal funding to state fish and wildlife agencies that requires them to abide by relevant federal civil rights laws, related statutes, and executive orders.

To help them, we provide technical guidance on how to create model programs for accessibility. We also conduct annual reviews of fish and wildlife agencies that receive funding.

What does a model program look like from a public civil rights perspective? In Portland, Oregon, the Service’s Urban Wildlife Conservation Program embarked on a partnership that converted a landfill into a city park in the heart of a low-income and mostly minority neighborhood. Cully Park was born. Investing funding and expertise to help create a green space is an excellent example of how we can combine the resources of state, city, and various community partners to connect people with nature.

Another example is the Arizona Department of Game and Fish’s Limited English Proficiency (LEP) program. It offers a stipend to bilingual employees who can pass a proficiency test if they volunteer for interpreter duties. In addition, their LEP program includes contracts with companies that offer an array of language services, including translating documents.

We also ensure our visitors have access to accessible blinds, such as the one at Sutter National Wildlife Refuge in California. The Service works to provide access for people with disabilities to boating, hunting, wildlife viewing, and other activities at various locations throughout the nation.

The stories in this issue of the magazine draw connections between the work we do in the Service and Environmental Justice, prompting each of us to consider what access to nature means to others. To Cadena, who was born and raised on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota, this meaning is deeply personal and relevant.

“As a Sicangu Lakota it is important to me to ensure Unci Maka (Mother Earth) is free from contaminants and the oyate (people) have access to the land for hunting and fishing,” she says.

When you are out on the water, hiking a mountain, photographing the most recent bird for your life list, join us in reflecting on ways that we can make these experiences accessible for everyone.

Public civil rights specialists MARCUS BANDY, BRIAN LAWLER, KATHLEEN LUCAS, and MICHAEL SANCHEZ, Public Civil Rights Program, Headquarters

- This story is from our Open Spaces blog. It is also in the summer issue of Fish & Wildlife News, our quarterly magazine.

- More Fish and Wildlife News, including how to subscribe to our Fish and Wildlife News email list.