Townsend, Georgia – U.S. Marine Corps jets and helicopters rain thousand-pound bombs and 30-caliber bullets on a slice of the Altamaha River corridor. Gopher tortoises, flatwood salamanders and eastern indigo snakes benefit mightily.

Say what?

Welcome to a looking-glass world where bombs are good, the Pentagon is an environmental agency and the ever-expanding Townsend Bombing Range along the northwestern edge of the corridor protects critical greenways and endangered species.

Incongruities aside, the military has become one of the Southern conservation community’s biggest supporters. While federal law requires adherence to the Endangered Species Act, the Pentagon embraces conservation as necessary to fulfill its readiness and training missions.

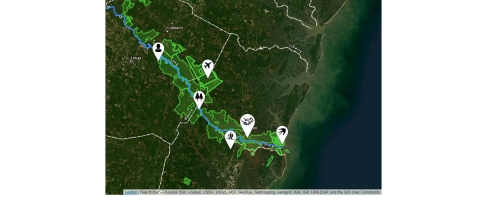

The Department of Defense is also the second largest financial contributor to the conservation of the 40-mile long Altamaha corridor. Stitching together the wildlife greenway from Darien on the coast to Jesup, near Townsend, has cost $93 million. DOD has contributed $26 million.

“The bombing range is an example of how different agencies can work together to preserve some good wildlife habitat,” said Robert Brooks, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Townsend. “It prevents habitat fragmentation. It’s not good for species when you have a block of land here and another there and development in between.”

Only a wide grassy field separated Brooks from Ground Zero, where the F-18s, A-10s and Apache helicopters drop their bombs and spray their heavy-caliber machine guns at immobile targets made from old shipping containers and the husks of tanks, Humvees and armored personnel carriers. The so-called “village” is made to look like a roundabout in an Iraqi town with containers as buildings and a couple of weapons-toting mannequins masquerading as bad guys.

Shrapnel, bomb fragments and bullet casings littered the weedy ground. Large craters – some of the inert, i.e. non-exploding, bombs are encased in cement and weigh 5,000 pounds – were filled with water. Holes large and small riddled the walls of the makeshift village.

“Most people find it rather odd that the military has such a strong conservation ethic,” said Colleen Barrett, a real estate specialist with the Marine Corps Air Station in Beaufort, South Carolina. “We’re able to provide funding to preserve this corridor in perpetuity for at-risk, threatened and endangered species which allows us to continue our military operations, protect water quality and (boost) public recreation.”

The village sits three miles from the Altamaha in the midst of the 5,200-acre bombing range. Fighter jets follow the river up from the Atlantic Ocean and drop bombs from altitudes reaching 20,000 feet. The range is used mostly by pilots from Beaufort, but squadrons from Shaw, Moody and other air bases across the South also unload on Townsend. Helicopter gunships and aircraft carrier-based planes target the village too.

Bombs are being replaced by “smart bombs,” aka precision-guided munitions, which necessitate a major expansion – 28,638 acres – of the Townsend range. (USMC officials acknowledge the “counter-intuitive” notion that smart bombs need more land.) A handful of new targets, including a mock-up airport, fuel depot and train station, will be added. Pilots from Beaufort will no longer fly to West Coast ranges to satisfy precision-guided training requirements. Expansion cost: about $110 million.

Most of the land, though, will remain forested as buffer zones keeping people and development at bay while protecting threatened and endangered species.

A sign on the edge of Townsend’s existing bombing range says “Flatwood Salamander Breeding Area.” It stands amid a copse of pine trees and alongside an ephemeral pond. It has been 15 years since a threatened frosted flatwoods salamander was last seen – in a water-filled bomb crater.

The Marines and their partners, though, hope to resurrect the salamander, as well as boost the habitat for other threatened or endangered species. They’ll restore nearly 10,000 acres of longleaf pine and burn the forests annually. Clusters of endangered red cockaded woodpeckers abound at Fort Stewart, an Army base 10 miles away. DOD has plans to join Townsend with Fort Stewart. The woodpeckers one day could fly unimpeded to Townsend – as long as they’re smarter than the smart bombs – and all the way down the Altamaha River.