In our dynamic world, where the harmony between nature and human existence is ever evolving, understanding the amazing journeys of migratory species as they navigate changing landscapes and cross hemispheres is vital for us to know how to best conserve them and their habitat. Through innovation and partnerships, we have begun a new chapter using cutting-edge technology to help us answer questions about the many wonders of bird migration. Through the Motus Wildlife Tracking System (Motus), researchers can now use advanced miniaturized digital radio-telemetry systems to track movements and behavior of tagged birds across vast distances and extended periods of time, like never before.

What is Motus?

Motus is the largest international collaborative research network that brings together organizations and individuals to facilitate research and education on the ecology and conservation of flying migratory species. The program is led by Birds Canada, in partnership with a growing network of scientists and organizations on almost every continent. The Motus system uses radio telemetry, a fancy term for using small radio transmitters (or nanotags) to track wildlife on the same frequency across the globe, and thenharnesses the power of scientific collaboration to collect and share data from across the world, amplifying the impact of everyone's work. This collective effort optimizes research and conservation resources, allowing for impactful data collection and monitoring of hundreds of species simultaneously, facilitating landscape-scale research. Motus is just one tool used to monitor migratory birds, but by pooling resources with partners through this network, we can contribute to a coordinated effort to improve conservation efforts on a global scale.

How does it work?

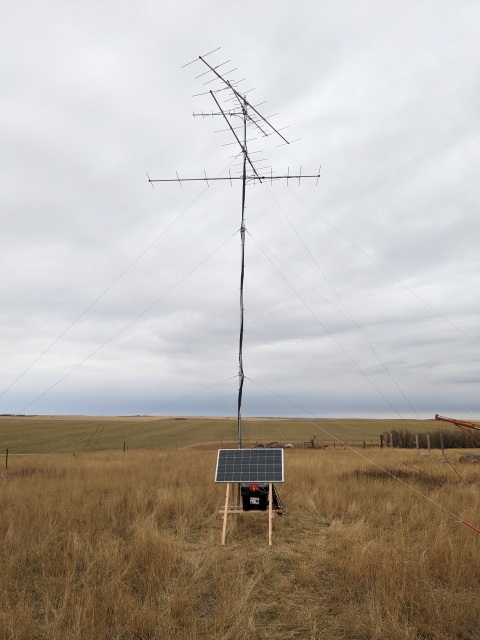

Researchers attach small nanotags to flying species, like bird banding, except these nanotags send out a signal when they fly by a strategically placed Motus tower that can be detected up to 12.4 miles away! The radio signals from these “pings” emit individually unique, digitally encoded radio signals that broadcast up to several times a minute on a shared frequency on all Motus stations in the world. The radio signals can provide data on a bird’s arrival, departure, length of stay and even how they use a habitat at key stopover sites. When a tagged bird triggers a “tag report,” the encrypted data is stored in a computer and downloaded every three months to Birds Canada’s public database, where they archive, visualize, and distribute the collected information to researchers and the public. By monitoring these details, scientists can answer research questions about the timing and seasonal duration of migration. This data also helps land managers better understand migratory birds' seasonal habitat use, allowing them to gain insights into the role that protected areas, like National Wildlife Refuges (Refuges), play as a stopover point or passage for migratory birds.

How big is this Motus network?

As of May 2023, Motus has grown to include more than 1,200 stations across 31 countries. Over 400 projects have used Motus tags to track at least 250 species of birds, bats, and insects, and the resulting data has been used in a growing number of academic publications. The power of partnerships and collaborative research is evident in the success of Motus, which is contributing to numerous conservation efforts across the world.

How is the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service involved?

The Migratory Bird Program (including Joint Ventures), National Wildlife Refuge System, and Flyways, are joining in the Motus network by connecting with partners across each U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) region. Together we are pooling our resources to monitor bird movements, providing valuable information on migratory pathways, stopover sites, and breeding and wintering habitats where Motus towers are located. By partnering with other organizations in the Motus network, we are expanding its reach and contributing to a collaborative effort to better understand and protect migratory birds.

Pacific Region (Hawai’i, Washington, Oregon, Idaho)

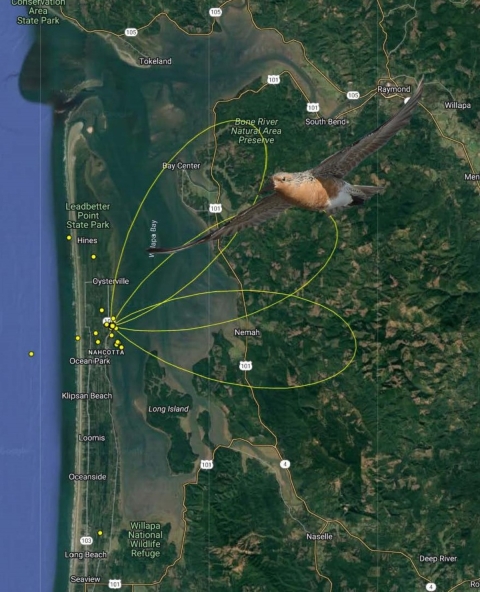

Every year, millions of birds migrate up and down the Pacific Flyway, yet there are still huge information gaps about how these birds use estuaries, beaches and coastal wetlands throughout their lifecycle. To address this, there are now dozens of Motus towers along the coast of Oregon and Washington to collect data on these birds, each receiving “pings” and providing our biologists and partners with information on bird movements, with a focus on shorebirds like Western sandpiper, sanderling, semipalmated plover, and dunlin. The region is also working with partners in Mexico on Birds of Conservation Concern such as the pacific red knot, one of the longest distance flyers of any shorebird. Motus is especially helpful for tracking species like red knots along the pacific coast as the towers can detect where the birds will be on estuaries, how they're using an estuary and how long they stay there by using nodes to triangulate where they go.

"[Motus] has been a valuable tool in researching shorebirds with very small populations. We really are learning more about offshore species and migrations occurring in different places… that subspecies are occurring in the same areas coming from different locations. Finding new areas where birds are congregating, where we wouldn't expect" said Vanessa Loverti, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Migratory Bird and Habitat Program (MBHP) Regional Shorebird Coordinator.

Ankeny National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon also recently developed an educational tool for visitors, the Willamette Valley Data Tap and Public App, and houses an interactive Motus data terminal. Refuge visitors can use this app to see real-time tracking information on migrating species, such as the number of times the tower has received a signal from a tagged bird, where that bird has been, and if it flew by other towers along its migration route. Check out this storymap to learn more.

Southwest Region (Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma)

Most migratory birds moving along the West coast typically do not make large overwater flights (unlike their eastern counterparts), but they still face many obstacles. As such, obtaining breeding movement and stopover site information for western migrants has been identified as critical information to the conservation of these species. Dan Collins, Migratory Game Bird Coordinator with the USFWS Migratory Bird Program, had a Motus study with sites in New Mexico, Texas and Oklahoma that gained new information on migration timing and population interactions of threatened snowy plovers breeding in the Southern Great Plains. They found that snowy plovers from a breeding area in Oklahoma made migratory movements to Texas and the Louisiana Gulf Coast at night. These findings may be important to long-term conservation and planning efforts for breeding populations of snowy plovers across the Southern Great Plains and beyond.

Adam Hannuksela, USFWS Science Coordinator of the Sonoran Joint Venture, has also been expanding the Southwest Motus network with the Western Motus Initiative and the Western Working Group of Partners in Flight, Bird Conservancy for the Rockies, Arizona Game & Fish Department, Pronatura Noroeste, and Tucson Audubon. The primary mission of the Western Motus Initiative is to expand the use of automated telemetry technology to provide information on western birds needed to develop effective conservation actions within the next decade. They are managing 3 stations in Arizona but plan to install at least 10 more towers once strategic locations are determined in New Mexico and elsewhere throughout the Southwest region. Adam is also creating workshops with the Bird Banding Lab to teach people how to tag, as the more birds tagged and the more people involved, the more information gained.

“The key to Motus is the network, so it will involve many partners in order to be successful,” USFWS Migratory Bird Biologist Corrie Borgman said. Corrie is partnering with the Department of Defense at Fort Bliss and White Sands Missile Range to install Motus towers.

Pacific Southwest (California, Nevada)

In 2019, the USFWS Migratory Bird Program worked with the Southern Sierra Research Station to expand the Motus network in Western North and South America. This initial work started a study of tricolored blackbirds to understand local movements of breeding locations and contributed funding for projects that have become a foundation of information in the region, now recognized as the Western Motus Initiative. Following that, a USFWS Directorate Fellows Program project was completed that worked with Partners inflight Western Working Group to identify gap areas which could be useful to strategically select locations to install Motus in California and Nevada. As a result, the MB program purchased equipment that was installed at the Don Edwards NWR and is operated by the San Francisco Bay Bird Observatory to contribute to Motus coverage on San Francisco Bay for Red knot, Western Sandpipers, and other species. This region is also coordinating closely through the Central Valley Joint Venture to study shorebird migration patterns and winter habitat use in California’s Central Valley. They have been collecting data to study how shorebirds are using the landscape in response to limited resources due to drought and timing of movements as climate changes and creating visual messages to engage the public with the results.

Grassland birds have declined more rapidly than any other group of land birds in North America over the last 50 years. To address this issue, Scott Somershoe, USFWS Migratory Bird Program Landbird Coordinator has been spearheading efforts with Motus to learn more about priority grassland songbirds such as Sprague’s pipit, chestnut-collared and thick-billed longspur, and Baird’s sparrow. Since 2019, this region now has close to 70 towers, many of which are located on National Wildlife Refuges throughout the central grasslands. Just between 2020-2023, the Service and partners deployed over 30 of these towers, tagged over 40 thick-billed longspurs, 94 Sprague’s pipits, 95 chestnut-collared longspurs, 35 Baird’s sparrows, and 25 brown-capped rosy finches. This has produced over 260 detections of grassland birds. The Northern Great Plains Motus Collaborative has also spawned from this work, where collaborations have formed with the Service and partners like Bird Conservancy of the Rockies and Smithsonian Institute for additional tower installation and bird tagging. This partnership plans to co-develop a more comprehensive plan for Motus in the Great Plains in the long term. In addition, the Kelly’s Slough National Wildlife Refuge in North Dakota is working with the University of North Dakota to tag birds on the refuge as both a partnership and an educational opportunity for students.

Midwest Region (Minnesota, Missouri, Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio)

In January 2018, there were 17 Motus stations in the Midwest – today, there are over 190! Since their first station placement in 2018, Missouri alone has recorded over 400 detections of Motus-tagged birds (and one bat) in the state. Sarah Kendrick, USFWS Migratory Bird Program Biologist and Chair of the Telemetry Initiative for the Midwest Migration Network, has helped lead efforts to expand the Motus network in this region and in the Neotropics working closely with five Midwestern state-agencies and organizations, including the Missouri Department of Conservation and Refuge managers who are actively involved in placing Motus stations.

There is a significant new Motus-tagging project for wood thrush being started across the Midwest, Northeast, and Southeast that will likely be the largest-scale Motus-tagging effort to date across a species’ entire range. This project involves international partners from Central and South America, with the goal of obtaining crucial data on the wood thrush breeding and wintering range. All wood thrush will be Motus-tagged within range of an active Motus station, allowing researchers to look at survival from both ends of the migratory range and investigate regional migratory connectivity. Based on 25 tags placed on wood thrush in spring 2022, there is evidence that the birds tagged in Costa Rica and Nicaragua are breeding in the northeastern U.S. and southeastern Canadian provinces. A broader sample of Motus tags deployed from across the breeding and wintering ranges will allow scientists to dive deeper into population-specific links between breeding and wintering locations and investigate drivers of population declines across the range.

Almost half of all migratory birds that breed in the Midwest leave the country in the nonbreeding season, up to 8 months of the year. Tracking birds before and during migration can help us to learn more about survival, where these birds are going, how long it takes them to get there, and whether they’re returning the following year. All this information helps us to better target conservation efforts along key migratory corridors or overwintering locations for species we share with the tropical areas of North, Central and South America.

“Motus has allowed me to make and grow amazing friendships with international bird-conservation partners across the hemisphere. We’ve had the opportunity to tag birds in the field together, learn from each other and plan future projects together to learn more about the shared birds that migrate between us” said Sarah Kendrick, USFWS Migratory Bird Program Biologist.

Emily Khazan, ecologist with the USFWS Inventory and Monitoring Branch, is leading the Motus network on Southeastern Refuges where they have been gradually adding towers on Refuges. She is working closely with the American Bird Conservancy’s U.S. Motus Coordinator Adam Smith to maintain the stations and to summarize data on 21 permanent stations along the Atlantic and Florida Gulf Coast. Emily collects data from the towers around migration seasons and sends relevant information on how that data relates to specific refuges regarding Birds of Conservation Concern and other endangered species we protect. They are also looking to fill knowledge gaps in the Mississippi Flyway, where they already have equipment in the region to work with-in the next few years. In general, the Southeast region is looking for a better understanding to what degree specific migratory birds are using Refuges to inform habitat management and to understand the impacts of that management. One of the species of focus has been the endangered red knot, where Motus data has already shed light on debated foraging patterns from spring to fall and what resources they need on Refuges across the coast.

In 2022, a Motus station was also installed in Puerto Rico at the Cabo Rojo National Wildlife Refuge in partnership with Birds Caribbean. The Caribbean Motus Collaboration (CMC) was formed to expand the Motus network in the Caribbean with the help of installation experts from the Northeast Motus Collaboration and as part of the Landbird Monitoring Project. Some towers in Puerto Rico have also been funded by our Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Act (NMBCA) grant program. For the Southeast region, Motus towers can catch birds on multiple migration paths and flyways. They can collect data on birds that might not otherwise be detected in other regions as they are located within two flyways and the Caribbean!

The Northeast states have the most Motus stations installed in any geographical area, but while most towers have been established on the land, there has been a special focus by the USFWS Migratory Bird Program in this region to expand Motus to marine environments to address information gaps relating to offshore movements of ESA listed species like roseate terns, piping plover, red knots, and other small shorebirds. Information on the migration routes and behaviors of shorebirds and seabirds is needed to conduct risk assessments and to inform the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s (BOEM) offshore wind assessment process. Pam Loring, USFWS Migratory Bird Program Wildlife Biologist has spearheaded these efforts which involved installing Motus towers on the Block Island offshore wind turbines and conducts workshops about how to manage them. In one study that focused on tagged piping plovers during fall migration, valuable information was gained by the Motus towers which can be used to estimate collision risk from offshore wind turbines currently under consideration across large areas of the Atlantic Ocean. They are also currently working with partners on a project to develop guidance for offshore Motus studies, including specifications and workflows for stations on turbines and buoys, study design tools, and tagging considerations. Products from the study are posted on a Motus offshore wind page and are currently being used by industry partners to install Motus stations throughout the Atlantic. In addition to this work being done offshore, the Service works closely with the Northeast Motus Collaboration and other partners to upgrade stations and grow the network from Massachusetts to Virginia, which were among the earliest stations in the Motus network.

There are currently 3 towers in Alaska with plans to expand to more locations. The existing towers are located at the Copper River Delta, Controller Bay, and Beluga, all in coastal southcentral Alaska. The U.S. Forest Service Chugach National Forest is responsible for towers at the first two sites and the Pronatura Noroeste, a Mexican NGO is responsible for the site at Beluga. All three towers focus on tracking migratory movements of shorebirds. As for plans to expand, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game and Alaska Peninsula and the Becharof National Wildlife Refuge are considering adding towers at coastal sites on the Alaska Peninsula to support movement studies of emperor geese and brant. The USFWS Migratory Bird Program is also collaborating with the Department of Defense to install additional towers at several remote locations on the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort Sea coasts. However, maintaining Motus equipment at remote sites with minimal infrastructure and severe weather is no small task. The next step in this planning process is to gain a better understanding of how these sites might benefit research and conservation efforts within the Pacific Flyway.

The U.S. and Beyond!

In addition to our work expanding the Motus network in the United States, we have also funded several Motus towers abroad. Through the NMBCA grant program, we have helped expand this international collaboration by funding additional Motus station installation and research across the Americas, including the first Motus bird monitoring network in Mexico.

A Future with Motus

While Motus has its strengths, it is not without challenges. Each station placement requires careful consideration. Lightning strikes can damage power sources, animal chews can disrupt data access, and noise interference may affect the accurate reception of pings, impacting readings and data collection. Maintenance can also be challenging, especially during severe weather events. It requires dedicated personnel who can travel across regions to install, maintain, and fix stations.

Despite these challenges, the complex research questions that can be answered and the international collaboration the network facilitates are believed to outweigh the disadvantages. With nanotags being the only transmitter that can be used on small birds and large insects like Monarch butterflies and large dragonflies, weighing as little as 0.2 grams, Motus stands out. As technology improves and more birds are tagged, the long-term benefits are expected to increase. Motus emphasizes collaboration and partnership, recognizing that no single person or organization can address the complexities of migratory bird conservation alone. By working together, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and our partners can make significant strides in conserving and managing bird populations across the United States and beyond.

All banding, marking, and sampling is conducted under a federally authorized Bird Banding Permit issued by the U.S. Geological Survey.