This is Climate Close Ups: an audio series that brings you the voices of those working against the tide of global climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change through their daily work. It’s an opportunity to look at the individuals behind the work and what drives them.

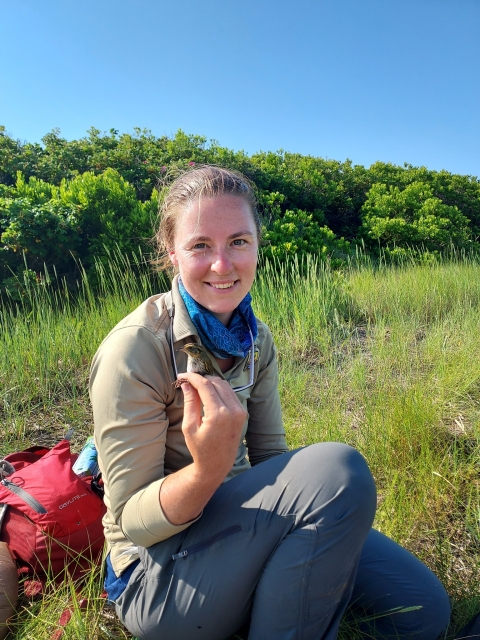

Bri Benvenuti told me she never set out to be a “bird person” but from a young age, she did aspire to be a wildlife biologist. And her path -- from her undergrad internship to her master's thesis -- kept leading her back to the shorelines of Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge, where she's now the biological technician. There, the salt marsh salt marsh

Salt marshes are found in tidal areas near the coast, where freshwater mixes with saltwater.

Learn more about salt marsh sparrow captured her heart. A highly specialized bird who can only live in salt marsh ecosystem, the sparrow, to Bri, is a sort of coastal canary in the coal mine that responds to changes and can show us where the ecosystem is failing. Now Bri is doing what she can to restore their habitat and build resilience back into the entire marsh ecosystem.

I sat down with Bri when I visited Rachel Carson in April. This was our conversation.

Listen to our conversation with Bri Benvenuti HERE

Transcript

Olivia Gieger: Hi, Bri, thanks so much for joining me. Let's start off by having you introduce yourself and tell me about the work that you do here at Rachel Carson.

Bri Benvenuti: Hi, I'm Bri Benvenuti. I work at Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge as a biological technician. So I've kind of worked on two different components of some of our sparrows and salt marsh restoration. So I do things like find nests for salt marsh sparrows so that we can monitor the productivity. We know that by going out and counting the birds you certainly get a handle on the overall population size, which we certainly need to help manage the species. But we also know that the best way to understand how salt marsh sparrow populations are doing are to actually monitor the nest and count how many chicks we're producing over time. So for example, with the salt marsh sparrow, I think it's around 45% of nests between 2011 and 2015 failed to produce a single chick for us. To be able to figure out the best ways of helping to protect their habitat and help them raise as many chicks as possible is to learn very specific details about their nesting. Where do they like to build their nest? Is it under tall grass and under short grass? Do they build a canopy over the top? Are they picking certain areas of marsh over others? How do they move around the marsh? They are a bird and they do fly but these birds are homebodies, and what we know is not only do they like return to the same marsh, year after year after year, the females salt marsh sparrow will come back and pick the same nesting spot. And it's one of the most astounding things -- one of my favorite things about the species-- but what that also means is that if you do something that drastically changes the habitat there really quickly, such as you know, replacing a bridge that lets more water in, she's not going to be adapted to that flooding cycle. She's not necessarily going to move to a different marsh down the street a couple miles away, maybe not even to the other side of that same marsh. And it can just make management a little bit more challenging because we need to do things that are going to change the habitat. But we have to do them in a way that we're not going to harm them in the process. So by doing this very specific kind of individualized work, finding nests and tracking them over time, we can start to answer those sorts of questions which then guide the larger questions like how do we help our salt marshes persist long term? What can we do to help the marshes build elevation to be stronger throughout the lifespan of the marsh and not just the bird?

OG: Yeah, so what is that like, asking those questions, then trying to answer it in terms of helping them marsh and through helping the marsh, helping the salt marsh sparrow?

BB: Salt marsh sparrows are so intricately tied to the marsh system. You can have a salt marsh that doesn't have salt marsh sparrows, but you can't have a salt marsh sparrow without salt marshes. So when you have a species of so intricately tied to the marsh system itself, if they start declining, the chances are everything else that uses that system or the marsh as a whole is also experiencing similar problems. So for the salt marsh sparrow, it's flooding, and the flooding is predominantly due to sea level rise, but really what they need is this balance between the elevation or the height of the marsh itself, like how high the ground is, relative to how high the water comes. And what's happening is the water is getting higher than the marsh surface. And when that happens, then the birds nests, the chicks can't climb high enough out of the grasses or the eggs can't stay in the nest and they float away. That's why the species is declining so rapidly. But what it's also showing is that we know the habitat is changing really quickly as well. And so we're losing those different services that the marshes provide to our coastal communities.

OG: Yeah. So how do you see this loss of services and the local teams of saltmarsh sparrow habitat as part of global climate change?

BB: I think my work is on the frontlines of climate change because the species is so closely tied to nesting between flooding tidal cycles, which we know not only is tied or tides getting higher with sea level rise and climate change. But that window between two different flooding events where salt marsh sparrows need to lay their nests and raise their chicks is shrinking over time as well. So throughout my tenure with the Fish and Wildlife Service, I've been watching the species declines. Salt marsh their populations have declined over 85% in the past 15 years. You know that essentially, that's four out of every five salt marsh sparrows is gone from our landscape. So I'm seeing those effects every single day and being able to work together with partners both in the Service and outside of the Fish and Wildlife Service to try to figure out solutions to protect not only the salt marsh sparrow from going extinct, but also for that whole entire marsh ecosystem. We need to have solutions to keep those marshes around for both birds and for the communities.

OG: Your career especially is so intertwined with the refuge. So I'm curious if you could tell me about the changes that you've seen just over the time that you've been here at Rachel Carson.

BB: It really started hitting home for me probably around 2016. I could really start to see changes mostly in our system. So one of the the marshes, Eldridge Marsh, in Wells, Maine. There's spots of the marsh that you used to be able to walk across with no problems at all, you know, beautiful grass, a lot of bird nests, and then it was almost like a switch flipped and now the marsh is really degrading and falling apart. It feels like every other step you take, you're in a hole sinking up to your hip. The vegetation has changed from that really nice, lush soft grass into alterniflora, which is this taller, stiffer wetter grass. There aren't nearly as many birds nesting in those areas as there used to be. When you sit and really think about what you used to be able to do in terms of an activity or walk and things like that, it all starts to sink in, and it's a little scary.

OG: Yeah, it is. But I'm curious where you see some of the work that you do, in a more hopeful light, as resisting and fighting back against some of this looming threat of climate change.

BB: You know, we're not going to stop climate change. It’s something we should certainly strive to, to at least slow or reduce -- that is something that is worth doing. But stopping it completely or outrunning it is not, in my opinion possible over time. So we need to figure out what can we do to support our ecosystems and make them have the best chance possible at persisting this enormous challenge that they've never faced before. And so, for me, you know, going out and figuring out how we can use those nature-based solutions to strengthen our marshes and help them build elevation and give that marsh and the ecosystem every opportunity that it can to persist over time, I think is one of the biggest ways that we can contribute to conservation these days.

OG: Yeah, and beyond your work specifically, wat do you want the wider community to know and the general public -- Where would you offer them hope in the face of climate change when it comes to the saltmarsh sparrow?

BB: The plight of a salt marsh sparrow can be pretty gloomy. You know, it's a species that's so closely tied to our salt marshes, and we know that in the marsh habitat itself we've been losing pretty dramatically over the last 50 years. Salt marsh sparrow populations are declining rapidly. Like I said, you know, we've lost four out of five of all of our salt marsh sparrows, and it's something that the Fish and Wildlife Service has taken a real interest in and has helped to gather a lot of momentum to help conserve the species and the habitat. And so I like to think of us kind of as you go out onto the marsh and you're watching the birds and the females do all of the work for the salt marsh sparrow and they arrive, they build a nest, it usually fails and then they immediately within a couple of days are re-nesting and again, and just trying to raise their chicks. I think that us humans can take a page from their book and knowing that we're working to conserve the species and the habitat, and we have to be a little experimental and try different techniques on what can help build marshes to help the species persist. and if something doesn't work, just regroup and try again because the other option is to not do anything, and we pretty much know what that outcome is. So by working together and just brainstorming and doing everything that we can to try to protect this really awesome species and habitat, I don't think we can go wrong.

OG: That's a great image of resilience. That is exactly the word that is so central to so much of this coastal work and marsh work is like how do we build more resilience in the ecosystem and also in the communities around it? Like how do we respond to these great challenges?

So Bri, thank you so much for being here and talking with me. This is really educational for me and truly a pleasure. I appreciate it.

BB: Thanks for listening.

OG: Thank you again to Bri Benvenuti and you for joining me in this conversation. And special thanks to the staff at Rachel Carson national Wildlife Refuge for facilitating this great visit in April. I’m Olivia Gieger. Editing and interviewing have been done by me as well as Mason Wheatley.

We'll see you next time.