Invasive species in the United States cause more than $100 billion worth of damage each year! While the financial cost of invasive species invasive species

An invasive species is any plant or animal that has spread or been introduced into a new area where they are, or could, cause harm to the environment, economy, or human, animal, or plant health. Their unwelcome presence can destroy ecosystems and cost millions of dollars.

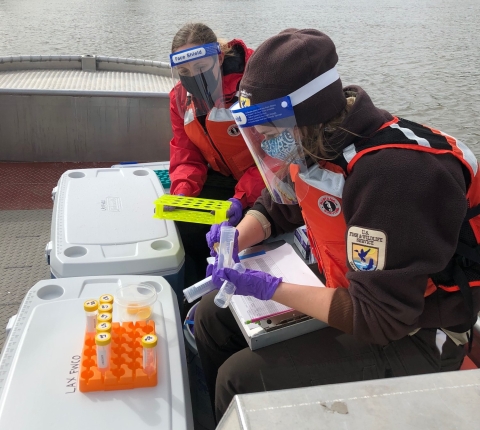

Learn more about invasive species is staggering, these invaders also wreak havoc on our ecosystems and threaten vulnerable native species. But scientists at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service may have found the key to catching unwelcome species early and giving species in peril a leg (or fin) up. Fisheries biologists are using environmental DNA, known as eDNA, to determine the presence of invasive, threatened and endangered species to inform management decisions. All it takes is a small sample of water.

Aquatic organisms constantly shed cells containing DNA into their surroundings. These organisms leave DNA behind in the water in the form of skin cells, feces or mucus. Biologists collect water samples and analyze them for the presence of specific species’ DNA. When biologists are looking for a proverbial needle in a haystack, or detecting organisms in low abundance, eDNA is particularly useful. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has been using this technique since 2013 for invasive carp surveillance.

eDNA in tracking invasives

In the Great Lakes, aquatic invasive species are one of the most significant threats to the ecosystem. The Great Lakes are an internationally treasured resource and are vital to the region’s economy, recreation and biodiversity. Second to prevention tactics, we use early detection monitoring to equip natural resource managers with the tools and information to respond rapidly to new invaders while their numbers are still small and localized. Catching new aquatic invasive species early is key to preventing them from gaining a foothold in our waters.

Imported to the United States for use in aquaculture ponds, black, grass, bighead and silver carps found their way into the Mississippi River system through flooding events and accidental releases. These species are fast growing with hearty appetites and the ability to out-compete native fish. Bighead and silver carp are filter feeders, consuming microscopic plants and animals that are the food base for a number of native invertebrates, freshwater mussels, snails and fish species. Today, silver and bighead carps are in the Illinois Waterway, about 47 miles from Lake Michigan and the Great Lakes.

Using eDNA, staff at the Whitney Genetics Lab in La Crosse, Wisconsin process water samples taken from the Great Lakes and Mississippi River systems, including the Chicago Area Waterway, to detect and monitor the presence of invasive carp – bighead and silver carp. The Whitney Genetics Lab is an active research facility and processes 8,000 to 10,000 samples each field season, which runs April through November. Patterns of positive eDNA findings in waterways over time give federal and state resource managers clues about where the leading edges of invasive carp populations are located.

Unintentionally introduced to the Great Lakes through ballast water discharged from commercial cargo ships, invasive zebra and quagga mussels rapidly spread throughout the Great Lakes and Mississippi River basins. Additionally, these species spread to numerous watersheds throughout the eastern and central United States and water bodies west of the Rocky Mountains. Currently, invasive zebra and quagga mussels are some of the most problematic aquatic invasive species in North America, causing disruptions to delicate food webs and increasing aquatic plant growth. The potential ecological risks posed by these invasive mussels and their ability to spread rapidly makes early detection crucial.

We are working with the U.S. Geological Survey to conduct early detection of invasive mussels through rapid eDNA testing of imported specimens of moss balls, which have recently been found to be a pathway for zebra mussel spread in the United States. In 2015, Columbia River Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office incorporated eDNA into the annual aquatic invasive species monitoring regime at lower Columbia River Basin National Fish Hatcheries to improve the probability of detecting these potential mussel invaders. The Columbia River Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office is broadening eDNA sampling at the hatcheries to test for five high-risk invaders including zebra and quagga mussels, New Zealand mudsnail, northern pike and common carp.

eDNA in conserving species

The increased sensitivity of this method is a valuable asset not only for invasive species but also for species of concern, threatened species and endangered species.

Biologists use eDNA survey methods in the Northwest to assess distribution of threatened bull trout and identify watersheds where bull trout are at risk of extirpation. Since 2016, the Columbia River and Mid-Columbia Fish and Wildlife Conservation Offices have been working in partnership with the U.S. Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station to identify streams in portions of Oregon and Washington that support local bull trout populations. Biologists at the research station developed a model that predicts where bull trout natal areas occur throughout the northwest. Biologists are collecting eDNA samples in predicted natal areas where bull trout populations are not known to exist to determine if those areas are currently occupied by bull trout.

Additionally, eDNA is used as a non-invasive tool to assess the distribution of native Pacific lamprey in the Columbia River basin where state, tribal and federal agencies are working toward species recovery. Native Pacific lamprey are considered a species of concern with recent data indicating a reduction in the distribution of Pacific lamprey in many river drainages and a decline in populations throughout the Columbia River basin and southern California. Since 2016, the Mid-Columbia Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office has been working with the U.S. Forest Service National Genomic Center to describe Pacific lamprey distribution in north central Washington. The Yakama Nation and Colville Confederated Tribes have used these distribution results to inform reintroductions and boost lamprey populations in historically occupied streams. The Columbia River Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office has been conducting a study in partnership with the U.S. Geological Survey to determine stream sampling intensity for eDNA techniques used to detect Pacific lamprey presence. Together, we are attempting to determine if sampling only at the mouths of headwater streams is sufficient to identify streams supporting Pacific lamprey.

Over the years eDNA has helped us hold the line against aquatic invaders and identify locations of hard-to-find threatened or endangered organisms. We are using the versatility of eDNA to help us achieve our mission to conserve and protect our nation’s natural resources.