Moose wondering through wetlands. The giant brown bears of Kodiak Island coming down from their winter hibernation spots. Of all the large iconic mammals that have come to represent Alaska over time, what about some of the smallest mammals found in North America and the only ones that are capable of flight? Bats!

The little brown bat is one of seven bat species that call Alaska home. They can be found across North America, as far south as central Mexico and have even been documented as far north as Kotzebue, Alaska and along the Yukon River north of Fairbanks.

A colony of bats often find humid and cool roost sites with consistent temperatures. Roost sites can be man-made structures, within tree bark, rock crevices and caves. Bats may have different roost sites depending on its use. These can include things such as maternity, hibernacula, and day/night roosting. Small numbers have been found using natural substrates in Southeast Alaska by the Alaska Bat Monitoring Program.

What’s on the Menu?

Bats tend to have specialized diets : nectar, fruit, pollen, small vertebrates, insects, fish and even blood (only a select few). For the little brown bat, insects are the meal of choice. As many people who live in or visit Alaska can attest to, there is no shortage of this food source in the summer months.

Fun Fact: Little brown bats can eat up to 1,200 mosquito-sized insects in an hour.

Aerial Acrobats

Unlike other mammals that glide through the air (such as flying squirrels and honey gliders), bats are capable of true and sustained flight.

DYK: Bats belong to a taxonomic group called Chiroptera, which means “hand-winged ones”. This is the second largest order of mammals behind rodents.

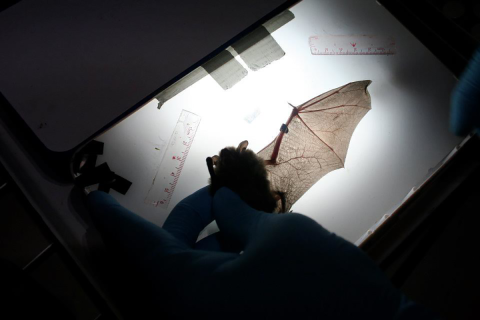

Bats have the same basic bone structure as other types of mammals, but they’ve been modified to have elongated arms and “fingers” that form their wing structure. The bat’s wing or “patagium” consist of the bat’s arms and hands with a web of skin between each finger that also connects to their hind legs. Their wing anatomy gives little brown bats the ability to move parts of their wings independently. This results in lift and sustainable flight. Pair this with their “tail wing” (uropatagium — there will be a quiz later!) and bats are capable of incredible maneuverability at high speeds (up to 22 mph) that many suggest is superior to many birds! Sorry birders, there is some competition in the air.

Night “vision”

Having the ability to fly is only part of the little brown bat’s story. The F-22 Raptor isn’t the only aerial hunter over Alaska with a radar to help find its targets, a little brown bat has a radar of its own. It is called echolocation. In the darkest of nights, rather than using primarily sight for navigation, they release a series of high-frequency clicks and squeaks, which are typically outside the hearing spectrum of humans, but detectable with specialized recording equipment. Much like an echo you create in a large empty room with the sounds bouncing around and back to your ears, a bat uses the “bounce back” to home in on locations of objects around them. A bat uses its specialized ears to determine the distance to the object based on the speed of the echo’s return. The intensity of the echo tells the bat the size of the object. A bat can determine what direction an object is moving as it analyzes the changes in sound returning. Echolocation makes little brown bats extremely effective hunters in zero visibility conditions.

A highly specialized tiny package

If you’re like most people, you haven’t had the opportunity to get a close look at a bat. They can be hard to spot in flight and we don’t suggest interrupting their roost sites. Their color can range from cinnamon to dark brown with gray coloration on their underside. Their specialized wings, ears, and noses are quite different from what you might be used to. And all in a tiny package (10 grams — about the weight of two nickels)!

Invisible but not Invincible

Being among the best predators of insects in the skies of Alaska does not mean these bats are invincible. For biologists studying little brown bats in Alaska, disease is on the forefront of their mind. White-nose syndrome is a fungal disease affecting hibernating bats across North America. The disease interrupts their hibernation, causing bats to wake up more frequently and burn through their fat stores, leading to starvation, and produces lesions in their wings. In many cases it is fatal (up to 90% mortality rate). Couple the low reproductive rate of bats (1 pup per year) with white-nose syndrome and other stressors like climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change , habitat loss, and other mortality factors, such as collision with wind turbines and you begin to see impacts.

There is much to be learned about little brown bats in Alaska. Formed in 2012, the Northern Bat Working Group has met annually to share and collaborate on information and projects involving bats. Projects, such as the ones occurring in Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge, provide data on winter and summer habitat use, and overall health assessments. These collaborations between U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, National Park Service and others aid in creating a network of trained bat handlers and data recorders for biologists to work with across the state and conserve these little aerial insect hunters.

Compiled by Kristopher Pacheco and Katrina Liebich, Alaska External Affairs, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, and Nichole Bjornlie, Ecological Services, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

In Alaska we are shared stewards of world renowned natural resources and our nation’s last true wild places. Our hope is that each generation has the opportunity to live with, live from, discover and enjoy the wildness of this awe-inspiring land and the people who love and depend on it.

Follow us: Facebook Twitter fws.gov/alaska/