Our country has a rich history of protecting animals and plants and the habitats they depend on. Over the past century, we’ve seen animals go extinct from unregulated hunting, over exploitation, and widespread habitat destruction. In response to the nation’s profound desire to protect wildlife, we’ve enacted laws and negotiated international treaties to demonstrate our shared commitment to creating a future where plants and animals are abundant, including the Endangered Species Act, Migratory Bird Treaty Act, and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

In addition, we’ve created regulations to ensure that human demands don’t continue to drive species towards further decline and even extinction.

However, we also recognize that there are times when human needs may conflict with a policy or regulation or require some type of exception as society’s demands for infrastructure, industry, or other types of development are needed to help communities across the country continue to thrive.

Permits can both accommodate the needs of people and provide a way to authorize those activities in a way that is consistent with the law.

To take it one step further, we can use these permits to monitor those human activities to ensure they are conserving wildlife and their habitats.

People may view the process of applying for permits as a way to “check the box,” but our goal under these conservation laws is to use permits as a tool to conserve species.

Laws that Protect Birds

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918

One of the most world-renowned conservation laws in history that set a precedent for protecting wildlife is the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 (MBTA). The very foundation of the MBTA was to regulate the unfettered and unprecedent killing of birds.

The lucrative feather trade for women’s fashion (particularly hats) in the 1800s drove many North American birds to the brink of extinction as they were killed by the millions for their showy breeding plumage to meet demand from across the globe. Networks of hunters were hired to supply bird skins and feathers. Whole hulls of ships containing nothing but bird feathers and skins were distributed to dealers, auction houses, warehouses and milliners (hat makers). Countless millions of birds were killed to supply this industry.

Thanks to the efforts of Harriet Hemenway, Minna Hall, the Massachusetts Audubon Society, and many others, the slow and steady swell of the bird conservation movement to protect birds eventually led to the passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which has served as a landmark law for more than a century.

Today, the MBTA prohibits the take (including killing, capturing, selling, trading, possession, and transport) of more than 1100 protected migratory bird species, and continues to serve as the main law protecting birds in the U.S.

The Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act

Many people don’t know this, but bald eagles were once considered “marauders” of livestock, preying on chickens, lambs and domestic livestock. Consequently, the large raptors were shot in an effort to eliminate a perceived threat.

Add that to the stressors of nesting habitat destruction and degradation, as well as contamination of their food source by the insecticide DDT, bald eagles once faced extinction.

In 1940, noting that the species was threatened with extinction, Congress passed the Bald Eagle Protection Act, which prohibited killing, selling or possessing the species. A 1962 amendment added the golden eagle, and the law became the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act.

The Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act prohibits anyone without a permit from "taking" bald or golden eagles, including their parts (including feathers), nests, or eggs. This law has been instrumental in the recovery of the bald eagle and continues to protect both bald and golden eagles today.

Why do we have permits?

Over the last 50 years, an estimated 3 billion birds have been lost due to many human activities including habitat loss and degradation, climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change , invasive species invasive species

An invasive species is any plant or animal that has spread or been introduced into a new area where they are, or could, cause harm to the environment, economy, or human, animal, or plant health. Their unwelcome presence can destroy ecosystems and cost millions of dollars.

Learn more about invasive species , pollution and direct mortality from things like colliding with infrastructure, electrocutions, and vegetation management.

Permits not only provide a means to balance human activities with conservation, but they allow us to monitor activities and build partnerships to determine how they affect birds.

Permits are the primary touchpoint we have with the public and are critical to ensure that human activities are consistent with the purposes of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act. Each law uses permits in specific ways to protect species. Regulations contain information on the types of permits available, application procedures, and issuance criteria under a particular law or treaty.

When we receive a request for a permit, we recognize that there may be a conflict or problem, but our job is to find solutions to these issues and find the right balance of benefitting birds and addressing conflicts. We recognize that there are times when we need to authorize take of a bird, and we take that very seriously. By asking questions about the necessity of an action, the timing of the action, or what other types of solutions have already been tried, we hope that we can meet the needs of the public and have a minimal impact on bird populations.

Permits can serve as tools to gather, share, and use species data to monitor and manage plants and animals. You can help conserve protected species by complying with these laws to ensure that your lawful activities are separate and distinct from those activities that harm birds.

What types of bird permits are there?

There are more than 20 different types of permits we issue under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act. Examples of activities we permit include raptor propagation, scientific collecting, rehabilitation, education, depredation, taxidermy, and religious purposes for Tribes.

Each time someone applies for a permit, that is an opportunity for us to learn more about what’s happening to birds on the landscape and monitor their populations.

Here are a few examples of how permits have helped conserve birds.

Success stories about Rehabilitation and Education

One of the most well-known professions that require permits to do such incredibly important work is that of licensed bird rehabilitators. The Service is deeply committed to working with others to conserve migratory birds, and this includes supporting a national permitting program and working closely with our partners who play an integral role in the care and rehabilitation of injured birds.

“Permitting individuals and organizations to rehabilitate wildlife is important to promote the diversity of our ecosystems. Many of the injuries that cause wildlife to be admitted for rehabilitation are directly and indirectly caused by humans. For example, electrocutions caused by birds hitting power lines, being shot by guns or arrows, hit by vehicles, poisonings from herbicides, rodenticides, etc. The importance of permitting the use of birds as educational tools allows the public to get up close to that animal and become personally “involved” with that animal’s story and hopefully want to protect them and the habitats they live in. The health of raptors in the wild is especially important as we face challenges like climate change and loss of habitat.”- Beth Lott, Audubon Center for Birds of Prey

Rehabbers get calls in the middle-of-the-night from concerned citizens, they frequently bleed more money than they bring in, but they pour their heart and soul into their mission to help wildlife. And it can’t always be easy – there are many times when animals come in that are in too poor of shape that they need to be euthanized. However, there are many times when the medical treatment animals receive is wildly successful and they can be released back into the wild!

Here are a few examples from one licensed rehabilitation facility, the Audubon Center for Birds of Prey in Florida, that has treated animals and released them back into the wild, demonstrating how these permits help conserve birds today and into the future.

This photo of Eugene is courtesy of Kim Begay and used with permission by the Audubon Center for Birds of Prey. Eugene was an eaglet that fell from her nest before she was ready to fledge and fractured her tibiotarsus (leg bone). We were able to work with the veterinarian to operate on her and pin the leg immediately after rescue, but the eaglet had no pain response in that leg after the pins were removed. The vets helped with providing acupuncture and Chinese herbs to help restore function to the foot, and she was able to regain feeling. She then had to learn how to hunt since she missed that natural education in the nest. After she was able to hunt, she was released back into the wild! Audubon’s EagleWatch program, which monitors over 1,200 nesting pairs of eagles, still keeps track of Eugene as volunteers can spot her leg bands.

After nearly 2 years spent recovering from electrocution, the Audubon Center for Birds of Prey was able release to this osprey back into the wild. Courtesy of Samantha Little with the Audubon Center for Birds of Prey. An osprey was admitted for care due to injuries caused by electrocution.After evaluation, it was found to have burned nictitating membranes, burns to both legs, vent, chin, and she also had severe damage to her flight feathers. She needed to receive extensive care and medication to help the burns heal and then spent most of her time in rehab giving her space and time to allow her new flight feathers to grow in. The rehab staff imped (a method used to replace broken feathers) a lot of feathers so that the new feathers coming in would be supported while they grew in. This osprey spent almost 2 years recovering from electrocution before she was able to be released. However, since she did spend so much time under rehab care, she was able to serve as a surrogate parent and help raise several baby osprey during the nesting season.

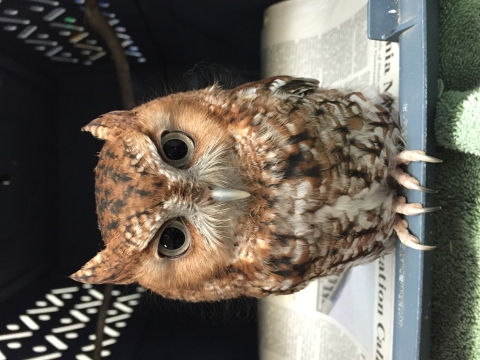

This young nestling great horned owl was admitted to the Audubon Center for Birds of Prey for rehabilitation. Courtesy of Samantha Little, Audubon Center for Birds of Prey. In 2020, there was a young nestling great horned owl that was admitted after being impaled by a branch. He was rushed over to the vet and was very lucky when we determined that no organs were affected, and we were able to surgically remove the branch. Once recovered, the bird was transferred to another rehabber to be raised by their surrogate and was able to be released soon after.

We know that not every injured animal can completely recover and get released back into the wild though. So what happens to them? Well, many rehabbers also have permits to use these injured animals for conservation education purposes. That way, the public can get up close to these wonderful creatures and learn about how to protect them and prevent future injuries.

Newman, an adult short-tailed hawk, was found caught in a barbed-wire fence. Upon admission, we saw that the tissue and tendons on part of the right wing had been severely damaged. In the U.S., short-tailed hawks are only found in Florida, Arizona and occasionally in Texas. Staff worked with our veterinarian who performed a series of skin graphs and used a special bandaging material to help the skin regrow over this damaged area of the wing. However, because of the extent of the injuries Newman could not be released, so he became a wonderful education ambassador at the Audubon Center for Birds of Prey for over 12 years, teaching many people from all walks of life about his species and how critical they are as part of our ecosystem.

Sanford, an eastern screech owl, was admitted for care as a nestling. He was very thin and had badly fractured his wing when he fell out of his nest cavity. Due to the severity of the fracture, Sanford was deemed non-releasable and has been a wonderful addition to our education program teaching adults and children how important screech owls are to the environment. He is also a social media star, lending another way to get people involved and invested in protecting Florida’s wildlife.

These are just a few examples from one bird rehabilitation organization. Across the country, thousands of birds are released back into the wild every year, making a big difference on the landscape for these birds and their ecosystems.

Success Story from the Smithsonian’s National Zoo Bird House Exhibit in Washington, D.C.

Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute (National Zoo) in Washington, D.C. has about two million visitors per year. Two million! People come from all over the world to see pandas, elephants, orangutans, and pythons on beautiful grounds right in the heart of the Nation's capital. And in the spring of 2023, after 6 years of being closed, the National Zoo re-opened its newly renovated Bird House.

The Bird House’s three walk-through aviaries are home to migratory songbirds, waterfowl and shorebirds native to North, Central and South American ecosystems. Educational signs, zoo staff, and volunteers provide information to visitors on how migratory birds play critical roles in pest control, pollination and seed dispersal for trees and plants as well as crops. And the education panels around the building are in English and Spanish to tell the story of how migratory birds connect communities and contribute to healthy ecosystems across the Americas.

And one of the most important things this monumental project required was...birds! In order to have birds under human care, the National Zoo maintains permits and ensures that their activities are compliant with regulations.

"We issue permits for a wide variety of activities that include rehabilitation, education and exhibition, keeping airports safe, providing support to farmers and landowners, maintaining important utility infrastructure, and supporting academic research," said U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Migratory Bird Program Biologist Zach Ladin. "We worked closely with The Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute to authorize them to have birds for their Bird House exhibit, which helps connect people to nature through education and they get to see several amazing species that they don't have the ability to see in the wild."

“Now more than ever, raising awareness about the plight of migratory birds is key to their survival,” said Brandie Smith, Ph.D., John and Adrienne Mars Director, National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. “As visitors walk through our spectacular aviaries and see these beautiful birds up close, I want them to appreciate the awe-inspiring journeys these animals make every year and walk away with the desire and knowledge to protect birds and their shrinking habitats.””

This state-of-the-art facility now welcomes between 1000-1800 visitors each day, helping connect people to the birds in their backyard, the flyway they live in, and the entire hemisphere.

Success story from the Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma’s Grey Snow Eagle House in Oklahoma

The Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma’s Grey Snow Eagle House gives long-term care to permanently injured bald and golden eagles, provides rehabilitation care to Oklahoma bald and golden eagles, offers on and offsite educational opportunities, and participates in nationwide research endeavors.

They operate under several permits, which allows the facility to successfully conduct four distinct programs: Rehabilitation, Native American Religious Use (Long-term care of eagles), Education, and Research. The Grey Snow Eagle House is the only facility in the entire country that possesses this combination of permits.

The rehabilitationprogram allows them to bring in injured Oklahoma bald and golden eagles and work with their veterinarian to release them back into the wild. They see eagles injured with gun shots, broken bones, and soft tissue injuries. And as of August 2023, the eagle aviary has successfully released 45 eagles back into the wild!

Under the religious useprogram, homes are provided to bald and golden eagles from around the country that are not able to be released back into the wild. This program gives these injured eagles a place where they can live out their life in peace. It also allows for naturally molted feathers to be distributed out to members of the Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma.

The education team and ambassador birds travel around the state to teach the public about the conservation of eagles, raptors, and Native American beliefs.

The research team also has a partnership with Oklahoma State University to develop genetically based conservation tools for bald and golden eagles. This research includes detailed population genetics and genomics analyses conducted on eagles found throughout their North American range so that new information can be discovered and used to aid in management decisions.

Since it first opened in 2006, over 150 eagles have come through the Grey Snow Eagle House, utilizing 6 giant cages, a flight cage, an ICU room, quarantine cages, education cages, and feeder animal operations. This facility provides a home to those injured bald and golden eagles, whether they can be released or not, and has committed to educating the community about Native American culture and protecting eagles.

Additional Links and Resources:

Find a Licensed Migratory Bird Rehabilitation Facility Near You

The regulations governing migratory bird and eagle permits can be found in 50 CFR part 13, 50 CFR part 21 (Migratory Bird Permits), and 50 CFR part 22 (Eagle Permits).