As the heat of the day burns off and the pink of a summer sunset stains the horizon, tiny fur balls flutter out from road culverts into the cool evening breeze. The first to emerge at night, tricolored bats could almost be mistaken for moths. At only three inches long and the weight of a quarter, the tricolored bat is one of North America’s smallest.

Unfortunately, it’s also one of several bat species experiencing dramatic declines due to white-nose syndrome. On September 13, 2022, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced a proposal to add the tricolored bat to the endangered species list.

The little bat that could

Once common across eastern North America, tricolored bats are now rare across their range. It takes a keen eye and considerable patience to spot these vanishing bats today.

The tricolored bat is named for its multitoned fur: each hair is dark brown at the base, beige in the center, and rusty red at the tip. Though they seem inclined towards the dark shelter of caves and road culverts in the winter, in the summer, one can find these little “pips” hanging by their toenails wherever they can be hidden and undisturbed. This includes under bridges, hidden in treetops, leaves, Spanish moss, and even abandoned squirrels’ nests.

Tricolored bats are some the hardest-working bats around and spend a ton of energy just to maintain their body temperature. Unlike most bat species, they roost alone, meaning they don’t benefit from the warmth of other bats. Despite their small size, these overachievers give birth to twins. During pregnancy, the pups can make up more than half the mother’s body weight and even a non-reproductive individual can eat half its body weight in insects each night.

White-nose Syndrome

The first among North American bats to hibernate and the last to emerge in late spring, tricolored bats are secluded in culverts and caves for many months. This long hibernation period increases their exposure, and vulnerability, to a threat that is driving dramatic population declines across their range.

First documented in North America in 2006, white-nose syndrome has since spread to 38 states and eight Canadian provinces. The disease is caused by the pathogen Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Pd), a fungus that is not native to North America and was unknown to science until it began decimating bats in New York. Pd often presents itself as white fuzz on the noses of bats, giving the disease its common name.

Thriving in the same cool, dark spaces where bats like to hibernate, Pd has caused white-nose syndrome in 12 of North America’s 47 bat species, including three protected under the Endangered Species Act. The fungal infection causes strange behaviors, including waking early from hibernation. With nothing to eat on the winter landscape, victims burn through their fat stores and starve to death before spring arrives. According to a study published in Society for Conservation Biology, the disease has killed more than 90 percent of affected northern long-eared, little brown, and tricolored bat populations in less than 10 years.

Fighting the Fungus

The ability to document these devastating losses is itself a scientific achievement. Until 2015, bat-monitoring data collected separately by state and federal agencies was compiled only for federally protected species. When white-nose syndrome began wreaking havoc on North American bats, all three of the hardest-hit species were abundant. In response to the disease, the U.S. Geological Survey, the Service and many partners launched the North American Bat Monitoring Program (NABat) to improve conservation science for bats. This program has been integral to the collection and assessment of historical data that helps us better understand what is affecting bats today.

The development of NABat is one of many accomplishments stemming from a Service-led international response to white-nose syndrome that coordinates the actions of more than 150 partnering non-governmental organizations, institutions, Tribes, and state and federal agencies. With all hands on deck, this community of bat conservationists is bounding from breakthrough to breakthrough in the race to protect these incredible animals. An unknown fungal pathogen in wildlife has never been so quickly characterized. This initial effort spurred over a decade of research on methods to combat the pathogen on all fronts Together, we are:

- Testing white-nose syndrome treatments and other disease management measures – including but not limited to vaccination and treatment with probiotics to reduce mortality -- in nine states and British Columbia Closely studying bat populations to determine health and survival of bats that have repeatedly contracted white-nose syndrome and estimate vulnerability of bats recently or not yet exposed to the fungus

- Conducting genetic investigations to determine the potential for species to develop white-nose syndrome resistance, which could lead to gene therapies or biotechnological solutions

- Aiding recovering bat populations by identifying and protecting roosts important to susceptible bats and treating hibernation sites to reduce fungal loads and improve bat survival

- Investigating ways to boost post-infection healing, including heated bat boxes and artificial light lures that attract insects and habitat restoration projects that increase insect prey for bats

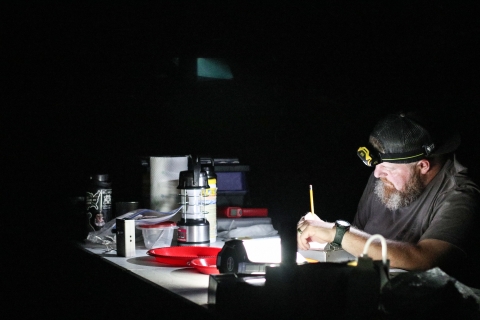

“We have developed an entire community of practice with transportation engineers, mycologists, microbiologists, and bat biologists to talk about what is going on with bats as a whole,” said Service Biologist Laci Pattavina. “These partnerships are so important to bat conservation because in order to gather essential information, we need boots on the ground and folks coming at the issue from all angles.”

Crucial critters

Help can’t come soon enough. Bats are essential pest-control agents. A recent study confirmed that white-nose syndrome costs the agriculture industry between $426 million and $495 million annually in lost revenue and production. It is estimated that bats contribute at least $3 billion annually to the U.S. agriculture economy through pest control and pollination.

“White-nose syndrome is showing just how devastating an invasive species invasive species

An invasive species is any plant or animal that has spread or been introduced into a new area where they are, or could, cause harm to the environment, economy, or human, animal, or plant health. Their unwelcome presence can destroy ecosystems and cost millions of dollars.

Learn more about invasive species can be,” said Service Biologist Pete Pattavina.

“The silver lining to this listing is that we’ll learn so much more about these bats. We didn’t even know extent to which they [tricolored bats] roost on the landscape in tree hollows and branches or road culverts until there was a reason to start studying them,” remarked Laci Pattavina.

While Pd may be here to stay, bats returning to their roosts can rest assured that the Service and its many partners will press ahead to reduce the impacts of white-nose syndrome, hoping to turn breakthroughs into recovery for the tricolored bat and other disappearing bat species.