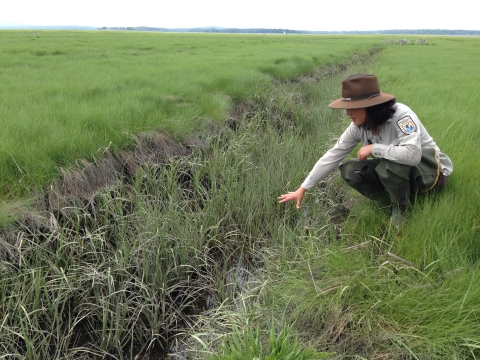

On the surface, there’s nothing particularly revolutionary about a runnel: it’s just a narrow channel through muck that drains water off a salt marsh salt marsh

Salt marshes are found in tidal areas near the coast, where freshwater mixes with saltwater.

Learn more about salt marsh . But for a bird species that depends on high marsh habitat to survive, those simple drainage channels may be a lifeline.

The only bird species that breeds solely in the salt marshes of the Northeast, the saltmarsh sparrow could face extinction due to rising seas. High tides and extreme storm events are increasingly flooding high marsh areas where the birds make their nests.

That’s why the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is working with partners to pilot nature-based techniques for restoring high marsh habitat in one of the largest areas of contiguous marsh in the region. Encompassing 28,000 acres on the north shore of Massachusetts, including all of Parker River National Wildlife Refuge, the Great Marsh is considered a priority area for the species.

For five years, partners on the Great Marsh have been testing techniques, including runnels, that biologist Susan Adamowicz from Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge in Maine and Geoff Wilson at Bear Creek Wildlife Sanctuary in Saugus, Massachusetts developed. Now for the first time, they are applying the entire suite of techniques to a 100-acre pilot area to see how the habitat responds when everything comes together.

The goal is to fine tune strategies for helping marshes, and saltmarsh sparrows, keep pace with sea-level rise by creating high-elevation areas with plant communities that support nesting habitat. Researchers at Parker River have meticulously monitored how the marsh responds to the trial techniques – as have managers in other coastal areas who are testing similar approaches. By comparing their results, they can calibrate restoration techniques to marshes with different characteristics.

“This work and the Great Marsh are really going to set a standard, I believe, for how other marshes can be restored,” said Russ Hopping, Ecology Program Director at The Trustees of Reservations, one of the main partners in the Great Marsh restoration. “I see a lot of interest building in thinking big, which is exactly what we need to be doing.”

With the pilot program complete, the team is moving to the next stage, scaling up successful restoration techniques to combat marsh degradation and protect the saltmarsh sparrow on the Great Marsh, and beyond.

Their strategy follows nature’s lead to restore tidal flow and elevation to the marsh. Though these techniques are simple, the benefits have been manyfold: habitat protection for the saltmarsh sparrow, flood resilience and water filtration, better carbon storage, and a beautiful natural space that instills a deeper sense of place for locals.

Salt Marsh Under Threat

“The saltmarsh sparrow is at the center of all of this work,” said Jade Fiorilla, who is working at Parker River as a research fellow with the Marine Biological Lab.

Protecting the saltmarsh sparrow means protecting high marsh, which is disappearing quickly as sea level rises and harmful historic alterations, like ditching and embankments, catch up to the marsh. Today, managers are seeing water pool in the marsh, instead of moving in and out with the tide. This standing water drowns plants and causes erosion of carbon-rich peat soil, leading to gradual sinking of the marsh and the transition of high marsh to low marsh or mud flats.

Saltmarsh sparrows have always had to nest at the right time and place to avoid super-high tides that flood the marsh every full moon. With nests built too low, chicks can drown, or eggs can float away. Too high, and nests become targets for predators. With sea-level rise, the sparrows’ habitat is washing out from under them.

Five percent of the global saltmarsh sparrow population lives on the Great Marsh, and research suggests that young birds from the Great Marsh add genetic diversity to other smaller marshes in the Northeast.

“If there's one spot in all of New England -- if there's one basket you want to think about for salt marsh habitat protection, particularly for saltmarsh sparrows, that's it. There's nothing else that compares,” Russ Hopping said of the Great Marsh.

The need to preserve the marsh habitat for the birds was clear. That’s why Nancy Pau, the wildlife biologist at Parker River, began plans for the 100-acre pilot, bringing Adamowicz and Wilson’s different techniques—runneling, ditch remediation, and microtopography—together in one project.

“The most important consideration for [the restoration teams] is to buy sparrows more time. The goal is that we want to keep saltmarsh sparrows in the landscape long enough for salt marsh [to build] back up to where it should be,” said Wilson.

Basically, managers implement strategies like runneling and ditch remediation to stabilize water flow and allow the marsh to build up sediment, so that eventually the marsh will build in elevation and restore these high-marsh nesting habitats on its own. Simultaneously, managers are trying to mimic high marsh by building thatch “microtopography islands” for the birds to nest in during the interim.

But the benefits that can come through restoring hydrology go far beyond the saltmarsh sparrow: It protects the local community from storm surge, maintains a cherished local recreation spot for birders, clammers, and beachgoers alike, and restores the marsh’s powerful carbon sequestering abilities. The marsh loses that ability when plants die off and peat subsides. It also loses the stored carbon, which is released into the atmosphere.

Refuge managers and their partners on the great marsh quickly recognized these benefits, in the context of climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change , and the need for working together across the marsh to preserve them.

“I just remember this one meeting we had, probably in 2015. We were all individually in the marsh and we were seeing really alarming signs: plants dying, pools forming, banks collapsing,” said Pau. "In that meeting when we realized the scale of the problem – that it wasn’t just on our land, it was everywhere in the Great Marsh – that meeting brought the urgency of having to do something.”

Salt Marsh Under Piloting and Planning

And do something they did. The four largest land managers on the great marsh--that’s the Service, The Trustees of Reservations, MassWildlife and Greenbelt--realized that, collectively, they own 8,000 acres, nearly 50 percent, of the Great Marsh. Together, they could make a sizeable impact on the majority of marshland by just starting with what they already own.

“As we were piloting these techniques on the refuge, we were sharing what we learned [with our partners, other landowners on the Great Marsh.]” said Pau. When the time came to work beyond the refuge, everyone was ready to hit the ground running.

“We wanted to demonstrate that these techniques are robust enough you could do them anywhere in the system,” Hopping said. It also means that salt marsh managers in different regions can follow the data to preview how their marshes might respond to the same techniques.

Already, such extensive research and data sharing is paying off, within existing partnerships. Trustees is restoring an 85-acre marsh using mainly ditch remediation. Mass Audubon is planning a similar marsh restoration project on its own marsh property—and taking these lessons beyond the Great Marsh. “This is our first restoration project on the Great Marsh,” said Danielle Perry, Mass Audubon’s Coastal Resilience Program director. “This will pivot us to other partnerships, like those on the Cape, Massachusetts’ South Shore, and Rhode Island.”

On the Great Marsh, the partners have about 3,000 acres of salt marsh in restoration planning right now and have another 8-10,000 acres on their radar for the next five-to-eight years.

“We’re using the same playbook. We are actually planning projects together. Now when we plan projects, we don’t even look at ownership boundaries. We look at watersheds and whatever makes sense for the restoration,” Pau said.

That partnership now generates more and more interest organically. As neighbors and smaller landowners have learned of the innovative restoration work underway, they’ve grown more interested and more involved.

“We've always been in the Great Marsh, and we've always had great partnerships. However, I will say this has taken it to a whole new level,” Hopping said. “It’s like a black hole in terms of gravity. Now the partnership is gaining gravity and scale, it’s pulling in others on its own. They’re getting attracted to what we’re generating.”