A day when you’d be likely to see the White Mountain fritillary is a day you’d want to be hiking through its habitat. The small orange and black butterfly, about half the size of the familiar monarch, is only found above 4,000 feet in the subalpine tundra of New Hampshire’s White Mountains. Encompassing Mount Washington — described in the Appalachian Mountain Club’s White Mountain Guide as “the most dangerous small mountain in the world” — it’s an area known for its extreme weather.

Based on windchill, the worst conditions recorded on Mount Washington are comparable to the worst conditions recorded in Antarctica. “Winterlike storms of incredible violence occur frequently, even during summer months,” the guidebook warns. In that kind of weather, a hiker might as well be a tiny butterfly.

That’s why the fritillary only flies in optimal weather. “The wind speed can’t be more than 15 miles per hour, and it needs to be sunny,” explained Katie Nolan, an American Conservation Experience (ACE) fellow for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. It also needs to be warm — at least 60 degrees.

The day I met up with Nolan was not optimal weather to search for fritillaries in their prime habitat, an area known as the Alpine Garden just below Mount Washington’s summit. The wind was gusting 35 miles per hour, and the wind chill was around 40 degrees. We couldn’t see the summit from the parking lot at the base of the auto road that leads up to it because it was engulfed in clouds.

Fortunately, Nolan and her fellow fellows have had plenty of optimal days to survey for the White Mountain fritillary during its four-week flight period this summer. Beyond the Alpine Garden, which is relatively easy to access thanks to the auto road, the fellows have completed 200 surveys at 87 locations throughout the Presidential Range. In addition to field identification for the butterfly and the alpine plants associated with its habitat, the fellows’ training at the beginning of the summer included mountaineering, orienteering, weather interpretation, and hours of hiking to prepare for a typical day’s work.

The extreme effort reflects the stakes. In 2008, New Hampshire Fish and Game listed the White Mountain fritillary as a state endangered species, citing threats to its narrow habitat niche from climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change and off-trail trampling. It is now under consideration for listing through the federal Endangered Species Act.

Over the past decade, the state has collaborated with conservation partners, including the U.S. Forest Service, Appalachian Mountain Club and the Service, to protect the butterfly, in part by learning more about it. Heidi Holman, project lead for species programs at New Hampshire Fish and Game, leads a multi-year research project to evaluate populations and better understand how the butterflies use their vulnerable habitat.

That involves creating a captive colony (more on that later) and repeating a two-year survey developed in 2012. “We needed to get a sense of population trends in the face of impacts,” Holman explained. Because it takes two years for the White Mountain fritillary to become an adult, they needed two years of data to develop a complete life-cycle picture.

They hired seasonal field technicians to conduct the first year of surveys in 2019. But the COVID-19 pandemic prevented New Hampshire Fish and Game from bringing on staff early enough this year to conduct surveys. That’s where the fellows came in, adding needed capacity on the ground on short notice.

“They filled a critical role so we didn’t lose that second year of data,” Holman said.

Crap shoot

While searching for butterflies near Mount Washington’s summit would have been fruitless the day I visited, there was still potential to find them someplace else. “If there’s a spot where there’s low wind, and the sun shines for half an hour, you can get a little burst of activity,” explained Steve Fuller, an at-risk species conservation liaison for the Service. “But it’s a real crap shoot.”

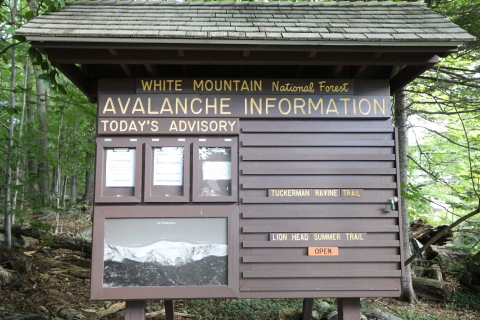

We decided to roll the dice. Instead of driving up the auto road, and hiking down into the Alpine Garden, we would hike up from Pinkham Notch, a saddle between Mount Washington and Wildcat Mountain, to a relatively sheltered area just above tree line along the Boott Spur Trail (named for 19th-century botanist Francis Boott, not footwear). That involved a moderately steep climb — about 2,500 feet of elevation gain over 2.5 miles — laden with the usual hiking essentials (food, water, layers, first aid), along with a clipboard for data sheets, a GPS unit, a weather meter, a collection jar and a butterfly net.

The last two items are used sparingly. (During our hike, the jar was used to collect berries.) “We don’t handle the butterflies unless we are going to bring them into the lab,” Fuller said. New Hampshire Fish and Game has permission from the Forest Service to collect up to 10 females in the White Mountain National Forest this summer to support the other part of the research initiative: the captive-breeding project run out of a makeshift lab in the Mount Washington Observatory.

Rather than join us on the hike, the other two fellows I met that morning, Allison Earl and Megan Zagorski, drove up the auto road to help tend to the butterflies in the lab.

“We keep them in red Solo cups with a sprig of vegetation, and the hope is they’ll lay eggs that can be reared in captivity,” explained Earl. The researchers release the females after about a week, giving them time to lay eggs again in the wild.

When I spoke with Holman a week after my visit, she reported that they had 180 eggs in the lab, two of which had hatched into caterpillars. The next stage in their life cycle is a long winter’s nap. Since 2017, Holman and her colleagues have experimented with different variables to try to reproduce conditions the caterpillars need to survive. They have honed in on the overwintering conditions; keeping them at 27 degrees through late spring, when the snow typically melts in their alpine habitat, produced a survival rate comparable to those of similar species in other successful captive-rearing efforts. But one key thing has remained a mystery: what they eat.

They know the adults feed on nectar plants in moist areas, but they have observed females laying eggs on different plants, in drier areas. Do they lay eggs in those areas because that’s what the caterpillars eat, or do they lay eggs there to spread them out as a defense mechanism against predators?

They don’t know, because the caterpillars haven’t eaten any of the variety of plants they’ve been offered in the lab. “We thought we saw nibbling on a blueberry plant once, but there were no signs of digestion,” Holman said. After five days, they released the hungry caterpillars in hopes that they would find what they needed in the wild.

The problem may be in the presentation. Some caterpillars won’t eat a cut plant because the chemistry changes, perhaps cueing them to pest damage or spoilage. Next year, they are considering releasing the caterpillars and following them to observe their eating habits — a contrast to the vigorous treks to survey for adults.

I asked Holman why the diet of the caterpillars is such an important piece of the puzzle. She explained that it will help reduce scientists’ uncertainty about what’s in store for this species.

“Climate change could force vegetation to shift, especially if a plant depends on snowbanks for soil moisture. If soil conditions change, will the plant the caterpillar depends on disappear?” she said. It’s a real concern, because many species of caterpillar will only eat one kind of plant.

“We need to understand its most essential habitat — the habitat it needs to complete its lifecycle — to be able to assess its viability into the future.”

With that understanding, the state, U.S. Forest Service, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service may be able to take proactive conservation actions to ensure the species has access to the habitat it needs to persist.

Butterfly weather

When Fuller, Nolan and I reached tree line on our trek up the Boott Spur Trail, we detoured to an outlook to take in the view.

“You see the riverbed there?” Fuller asked, pointing to a dry rocky chute between two ridges. “To the left of there, the ground is moist and protected. A snowbank would typically sit there until late in the year. If you were standing there, you’d see there’s a high diversity of nectar plants. For the same reason the snow holds there, it’s protected from the elements, so that’s the kind of place where butterflies tend to congregate.”

That’s why climate change makes the outlook for the butterflies less certain. Warmer winters could mean less total snow accumulation. Warmer springs could mean the snow melts earlier in the season. Either scenario could affect the plant community the species depends upon, in the adult stage if not others.

It was “butterfly weather” as we approached one of the survey points that was accessible from the Boott Spur Trail: 63 degrees and mostly calm, with just an occasional gust of wind. Nolan explained that when we reached the point, we would set a timer for three minutes to look for and count butterflies, and then record data on vegetation and conditions.

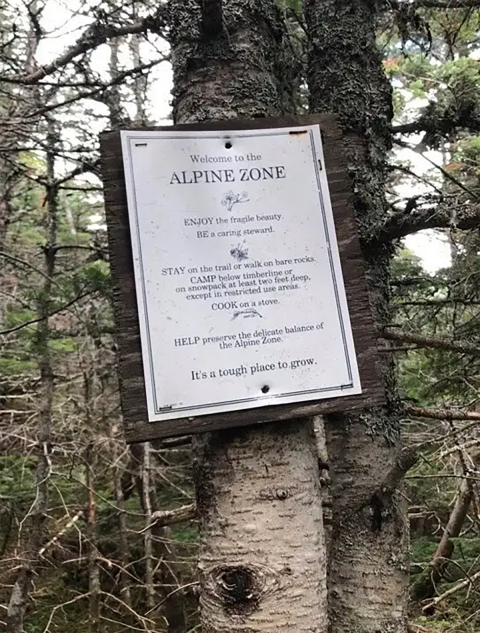

We left the trail (but you should not) to get to the point 57 meters northwest, treading carefully on tough mats of dwarfed black spruce and balsam fir to avoid stepping on more fragile groundcover. As we honed in on the site, shifting a few meters this way and that, waiting for the GPS unit to confirm our position, it started to rain.

We didn’t see a fritillary that day. But Nolan was hopeful that conditions would improve for the upcoming weekend, which would be the end of the fellows’ stint in the White Mountains.

By then I would be home nursing my sore quadriceps. But for the fellows, it would be the last chance to help reduce a little of the uncertainty about what this species faces in the future. Weather permitting.