Jesup, Georgia – “Well now, welcome to the swamp.”

Dink NeSmith stands astride a weathered wooden dock on Sandy Lake, a meandering offshoot of the Altamaha River. To some, the oxbow lake is nothing but a muddy, buggy, alligator-friendly bog.

To NeSmith, it’s an open-air cathedral in all its natural “majesty.”

“God put it here a long time ago,” he preached, “and it’s on loan to my family and me and we want to do our part to make sure it remains a clean, safe environment for our great, great, great, great grandchildren.”

NeSmith, 68, grew up in nearby Jesup, the son of an undertaker whose friends carried him into the woods and swamps to hunt and fish. He now owns the twice-weekly Jesup Press-Sentinel and two dozen other small newspapers in Georgia, Florida and North Carolina – as well as 4,000 acres along the Altamaha River.

A former Georgia Nature Conservancy board member, NeSmith built cabins from long-submerged cypress logs that never made it downriver to Darien. He turned an old turpentine commissary into a bunkhouse. He burns his pine tree stands to provide nourishment for gopher tortoises, indigo snakes and red cockaded woodpeckers. He put two-thirds of his land into conservation easements to keep it protected forever.

NeSmith also took on a solid waste conglomerate. And won.

A landfill operator wanted to send as much as 100 trainloads daily of coal ash to a nearby dump that sits alongside a tributary to the Altamaha.

“When I first heard mention of coal ash in Wayne County I said, ‘Whoa. Then no. Then hell no. We don’t want that in our river,’” NeSmith recalled. “We threw our heart into the fight and our wallets followed. I have never seen the community more riled up.”

NeSmith bankrolled much of the coal ash fight and wrote scores of scathing editorials in opposition. The company killed the project earlier this year.

He runs his newspaper empire from Athens, Georgia, but heads to the swamp whenever possible. Here, he fishes for mudcats and shellcrackers with a preacher pole. Deer, turkey and wild boar are ample. NeSmith will buy a mule and a wagon to take his grandsons quail hunting before he turns 70.

Nothing, though, seems to give him as much pleasure as riding the oxbows in a john boat, an anhinga or alligator within sight, while marveling at the centuries-old cypress trees with their knobby knees sticking up through the water.

“I will not be judgemental when I get to heaven,” NeSmith said, “but – should I get to heaven – if it’s not something like the Altamaha River swamp I’ll say, ‘St. Peter, what you got on the back side over there? I sure do hope there’s some oxbow lakes and cypress.”

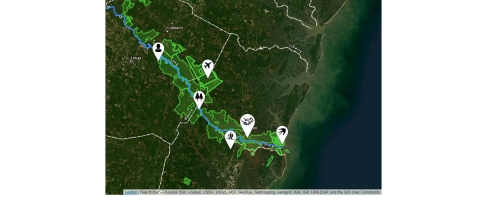

*Note: Green areas on the map represent protected local, state and federal lands.