St. Charles, Arkansas – Naomi Mitchell is the clerk and treasurer for this small White River town (pop. 230) renowned for duck hunting. She also, for a fee, plucks ducks clean. And, in her spare time, she runs the local museum, a folksy repository of many things St. Charles.

Tucked into a back corner of the museum, which shares space with the Town Hall, is an exhibit featuring the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps. It chronicles the construction work done by the young, dollar-a-day men of Company 1741 and Company 3791 who helped create a national wildlife refuge national wildlife refuge

A national wildlife refuge is typically a contiguous area of land and water managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for the conservation and, where appropriate, restoration of fish, wildlife and plant resources and their habitats for the benefit of present and future generations of Americans.

Learn more about national wildlife refuge from the bottomlands of the White River.

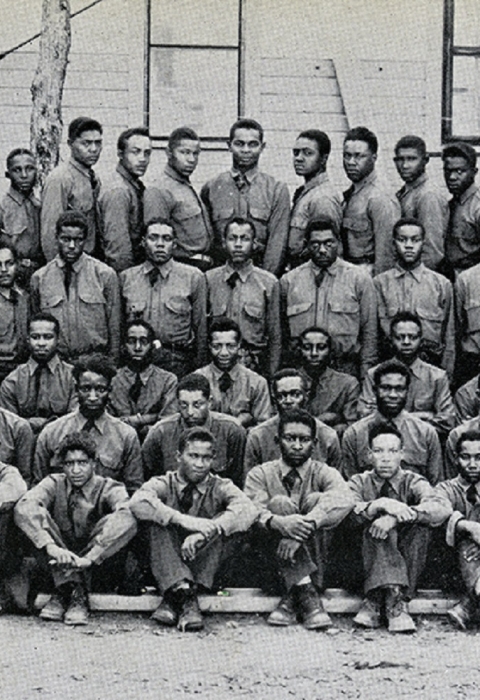

But there was another CCC unit that did the unsung work of felling the oaks, dredging the streams and laying the corduroy roads that ran through the refuge. Company 3776 was further down river, closer to DeWitt, and separated – in many ways – from the St. Charles’ units. Co. 3776 was all-African-American. Cos. 1741 and 3791 were all White.

“There was a time when they were all segregated,” Mitchell says. “I don’t know much about the Black camp.”

Richard Kanaski does. Kanaski, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) archaeologist, is compiling information about the little-known history of the African-American CCC enrollees throughout the South.

His immediate goal: Apply for National Register of Historic Places status for the Dale Bumpers White River National Wildlife Refuge.

His ultimate goal: Shine a spotlight on the major, yet largely hidden role played by African-Americans in rebuilding this country from the depths of the Great Depression.

“It’s part of our history and we’re working to acknowledge it,” Kanaski says. “We’re adding depth to the history of the CCC and, in particular, the African-American presence. They played a major role in the development of our refuges today.”

‘Two wasted resources’

In 1933, with the nation in the grip of the devastating depression, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt created by executive order the CCC. Men between the ages of 17 and 28 were paid $30 a month (with most of a paycheck sent directly to family back home) to build refuges, parks, hatcheries, levees, reservoirs, campgrounds, roads and trails across rural America. The Army-like program ended in 1942 as the nation ramped up to fight World War II and manufacturing jobs abounded. By then, more than 2.5 million young men had worked a CCC job.

The demand for work coincided with another necessity of American life circa 1930. Rural lands the country over were laid waste by poor farming practices and natural resource depletion. Eroded farmland immiserated already struggling families. Fish, ducks, deer, bear, beaver and other animals had disappeared from many fields, waterways and mountains. Droughts withered the crops, dried up the streams and, with the help of howling winds, sent mountains of once-arable soil into the sky.

One writer said Roosevelt “brought together two wasted resources, young men and the land, in an attempt to save both.” The CCC men had a job to do, and they did it.

They worked on more than 40 wildlife refuges, building roads, residences, levees and fire towers. They planted millions of trees, garnering the nickname “Roosevelt’s Tree Army.” They also restored riverine and coastal habitats critical for migratory birds.

In Arkansas, the CCC erected 450 buildings, laid 6,400 miles of road, planted 20 million trees and strung 8,600 miles of telephone wire. At White River, the young men basically created the refuge out of whole cloth. The White CCCers built the refuge buildings and residences. The Black CCCers, stationed downriver in Jack’s Bay, mostly built fences, truck trails, fire breaks, levees, and cleared the river channels.

Building Grassy Lake dam. Photo by Civilian Conservation Corps.

FDR established the refuge from bottomlands and farmsteads in 1935 with the mandate to protect and conserve migratory birds – mallards, Canadian geese, scaups, Gadwalls, prothonotary warblers – and other wildlife. The Service acquired 110,000 acres along a 60-mile stretch of the White River. The CCC helped raze “undesirable” farm buildings, re-plant hardwoods and create impoundments that attracted the birds.

“The Service told the architects, ‘We’re not a high-falutin’ agency and we don’t need glorious buildings. We need functional buildings where you can go in and clean the mud off your boots’ ” Kanaski learned from his research. “Some of the buildings built by the CCC are still standing today.”

The CCC-built compound in St. Charles sits on a bluff overlooking the river on the edge of town. Three brick homes with terracotta-tiled roofs stand nearby, though two are condemned. There’s also a fire tower, also condemned.

A corner of the museum is given over to an exhibit entitled, “History of CCC Camps in St. Charles.” Pictures show White workers building the refuge compound and living on refurbished river boats, known as quarter boats, along the White. More pictures of camp life grace the annual report and The Quack-Quack, the company newspaper.

Separation of duties

Mitchell ducks into her museum office and returns with an album of old photos. Inside are pictures of Black men cutting trees, milling the wood, pushing wheelbarrows and making duck boxes from bark. Although the men helped build the refuge, Mitchell says, they weren’t working in St. Charles so they’re not part of the exhibit.

“The White crews did most of the buildings,” Kanaski says. “The Black crews got stuck with the erosion control, earth-moving, the planting of trees and other tasks that promoted habitat restoration. The CCC, like a lot of other things at the time, was segregated.”

It wasn’t supposed to be that way. Roosevelt’s order creating the CCC stated that “no discrimination shall be made on account of race color, or creed.” Corps leaders, though, ignored the president and created separate White, Black and Native American camps with only a few exceptions in the North.

In the South, the reasoning was as twisted as the racism that ruled much of African-American life. Southern governors and state officials refused, at first, to fill the CCC ranks with Blacks. As one Georgia official said, “It is vitally important that negroes remain in the counties for chopping cotton and for planting other produce.” Others claimed that southern communities wouldn’t accept the mingling of Whites and Blacks.

Georgia was particularly opposed to African-American participation. No Blacks had been selected in Clarke County where they comprised 60 percent of the population. By July 1933, only 143 Blacks statewide had joined the corps; 3,567 Whites had. In Mississippi, only 46 African-Americans were enrolled.

Calvin Gower, writing in the Journal of Negro History, said Blacks finally made inroads into the southern camps by the mid-30s. Even then, though, their jobs were restricted by race. He quotes Robert Fechner, the CCC director, as rationalizing the admission of Blacks “because of the natural adaptability of Negroes to serve as cooks.”

In all, there were 150 segregated camps across the country. Eventually, African-Americans made up 10 percent of the CCC workforce, which was on par with national population figures. Yet scholars like Olen Cole Jr., who wrote The African-American Experience in the Civilian Conservation Corps, noted that Blacks suffered disproportionately higher levels of poverty and joblessness than Whites. And, while White enrollees were employed in the construction trades, Black enrollees were relegated to tree cutting, kitchen duty and mosquito-control projects.

“The contributions of all-African-American camps were vital to the development and maturation of the nation’s major parks and conservation infrastructure,” Olen wrote.

Now, nearly a century later, their largely unsung, yet critically important conservation work is finally getting its due.

Company 3776. Photo by Civilian Conservation Corps.