September, it seems, has become a month of dread for residents of the southeastern United States and the Caribbean. On guard 24/7, with headlines from NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center proclaiming “chance for above-normal hurricane season,” September harkens that all too familiar angst as residents sponge up every advisory issued by the National Hurricane Center. Woven together with data from satellites and sensors, citizens are fed an endless array of spaghetti models that are updated frequently, making real-time tracking possible for an ever-connected society. Tuned in and turned on, we watch their every move – Matthew, Harvey, Irma, Maria, Ian – from the time they are named to the time when they finally dissipate. These storms and the savagery they bring, dominate headlines…and our lives. Vastly different from the “cone of uncertainty” of thirty years ago, modern-day storm predictions make us realize that there was a time when ignorance truly was bliss.

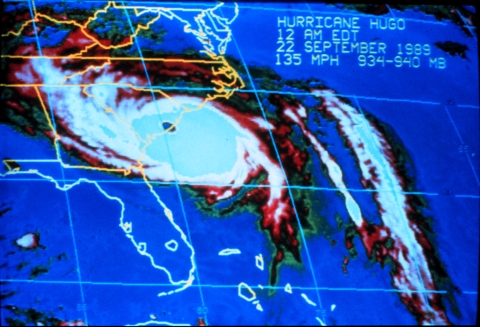

During the summer of 1989, the Atlantic Ocean saw a progression of 11 named storms, the most notable being the birth of Hurricane Hugo, on September 9, 1989. Hugo began as a tropical wave moving west off Africa and grew to become one of the most intense tropical cyclones to strike the East Coast north of Florida since 1898. It reached Category 5 strength before landfall in Puerto Rico as a Category 3. The storm sliced through Puerto Rico’s high terrain and weakened slightly before continuing its relentless march across the warm waters between Puerto Rico and the mainland. This tropical beast, with renewed furor, was South Carolina-bound - a cone of uncertainty no more.

As night fell on the South Carolina coast on September 21, 1989, many feared they would not see dawn the next day.

A night not soon to be forgotten

Hugo’s path brought the eye of the storm right over the Charleston region, unleashing the most powerful portion of the storm over the Awendaw-McClellanville area, home to Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge and the adjacent Francis Marion National Forest. Both areas, national treasures with their bountiful wilderness areas, were ripped, shredded, flooded, scoured…decimated. The crown jewel of South Carolina’s coast was now “ground zero” of Hugo’s wrath.

A 20-foot storm surge swept the region, spewing debris and wildlife for miles. Seabird and shorebird species that survived the storm (like skimmers, shearwaters, petrels, and terns) were blown inland up to 200 miles from the coast. Bodies of others not so fortunate littered the ground at places like Buck Hall Recreation Area in the Francis Marion National Forest. The smell of resin from all the felled pine trees hung thick in the air.

Hugo’s 130-plus mph winds had all but leveled more than a third of the 259,000-acre Francis Marion National Forest. An area that had experienced intensive timber harvesting from the late 1800’s to the early 1900’s, the Francis Marion was now managed by the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) and was a treasure trove of regenerated bottomland hardwoods, pines, and cypress trees -- some stands having trees that were 80-100 years old. Home to many native plant and animal species, the Francis Marion was now utterly devastated. Trees that weren’t uprooted entirely stood sheared off at least 10-25 feet above the ground.

While people throughout the area were reeling from the loss of their homes, the toll on the region’s wildlife was becoming very clear. The red-cockaded woodpecker, one of the southeast region’s most iconic endangered species, and a keystone species for the Francis Marion, had suffered a devastating blow.

Listed as endangered in 1970 and receiving protection under the Endangered Species Act in 1973, the range-wide population of red-cockaded woodpeckers had fallen to an estimated 10,000 birds by the time it was listed. Scattered in isolated, declining populations, the endangered birds had rebounded in Francis Marion prior to Hurricane Hugo. With 1,900 red-cockaded woodpecker cavity trees, and an estimated 1,765 birds in 500 active clusters or groups, Francis Marion had the second largest population of woodpeckers in the country. That was until the night of September 21, 1989. In the blink of a hurricane’s eye, Hugo felled 87% of the active cavity trees on the forest. With only some 200 cavity trees left standing, the race was on to provide homes for the estimated 700 birds that survived the storm.

Newly hired by the Forest Service and on the job just four short months, Craig Watson and his co-workers at the Francis Marion had gone about business as usual for most of the week leading up to Hugo. But, on the morning of September 21, 1989, with Charleston’s mayor and local weather forecasters looking more distraught, the fate seemed set. The ominous warnings that now blasted over everyone’s television sets and radios foretold damage and destruction the likes not seen from a hurricane in decades. As Watson recalls, “I made no plans to evacuate, but the storm turned and strengthened. We figured it was going to be bad in the aftermath – I just had no idea.”

The rush was now on to prep office and home – placing boards over windows, gathering supplies, and gathering family, friends, and co-workers for safe haven there in his quarters on Witherbee Road in the forest. With a full house, including his wife, and soon-to-be one year old daughter, Watson was set to ride out what was quickly becoming the nightmare over the Atlantic. Hugo would soon swallow the entire state of South Carolina and give them all a night they would not soon forget.

Hugo began making landfall during the afternoon of September 21, 1989, but as night fell, the noise outside foretold the catastrophe to come. As the calm of Hugo’s eye passed overhead around midnight, Watson briefly emerged from his quarters. Living there on the forest with a red-cockaded woodpecker cluster near his home, he saw all he needed to see – trees down as far as he could discern. Daylight would illuminate the evidence.

Picking up the pieces

The enormity of the devastation was jaw dropping. Trees were down everywhere. Then Watson heard them – distressed red-cockaded woodpeckers – everywhere. The cluster of cavity trees in his yard was gone. Watson watched as the weary birds flew to and fro, hovering in mid-air where cavity trees used to stand. Exhausted, the birds would fly to any nearby perch and roost in the open. Some were lucky enough to survive the storm, but time was ticking. Roosting in the open would spell doom, exposing the survivors to predators. So, after rallying help for the community, clearing roads, providing shelter, and checking on the safety of others, Watson packed up his family and sent them back to his native Tennessee, away from the chaos. It was time to focus on the birds and the calamity that was now the forest.

As the new Zone Biologist and Wildlife Program Manager for the Witherbee and Wambaw Districts of the Francis Marion National Forest, Watson was in his element. Having studied the red-cockaded woodpecker in college, this was his feathered baby. With roads not even fully opened, Watson was by himself for the first few days. He’d seen the devastation on the ground. Several days later, he finally got reports from overhead. Don Eng, the Forest Supervisor stationed in Columbia, South Carolina, would be the first to deliver that airborne assessment to Watson. Circling overhead in a small fixed-wing airplane and in touch with Watson by radio, he could hear it in Eng’s voice.

“It’s all blown down, Craig,” Eng said. “It’s all gone.”

In fact, it was almost all gone. The only area of the forest not blown down was the Waterhorn District of the Francis Marion National Forest. Jim Brotherton, District Ranger for the Witherbee District and Watson’s immediate boss made it clear to him: Watson was going to be in charge of recovering the red-cockaded woodpecker on this forest.

In hindsight, recovery from a storm of Hugo’s magnitude without modern-day technology and conveniences seemed like an insurmountable task. There were no cell phones, only landlines, and even those were problematic in the days and weeks after Hugo. There was no email. But fortunately for the Forest Service, they had the DG, or Data General, a form of electronic communication that preceded email. Watson put out a call for assistance via the DG and gathered help from near and far. Little did he know that what they were about to undertake on the Francis Marion would become a pivotal moment for red-cockaded woodpecker recovery – and not just on that forest.

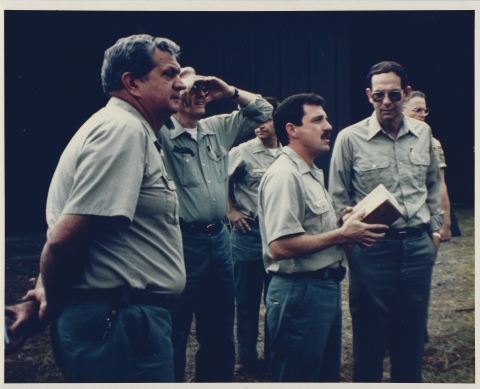

Help arrives

Crews arrived from other national forests, research stations, universities, and Department of Defense facilities. But the help that arrived with Carole Copeyon and Dave Allen was the game-changer. Copeyon, a graduate student from North Carolina State University, had worked the previous year on developing techniques for drilling artificial cavities in trees for red-cockaded woodpeckers. Allen, a red-cockaded woodpecker researcher with the Southeastern Forest Experiment Station located at Clemson University, had developed artificial cavity inserts that could be inserted directly into suitable trees.

Both techniques, in their infancy, had never been tried before on a large scale. This would be the grand experiment: the use of artificial cavities and inserts to help recover an entire population of red-cockaded woodpeckers.

The crews went into triage mode applying the techniques of Copeyon and Allen. Absent the luxury of time, and modern technology and armed only with tools of the trade, pure adrenaline, and determination, Watson and the recovery crews set about identifying suitable remaining trees and pairs of birds.

“We just found a suitable tree and went for it if birds were near,” Watson recalled.

And what better place to start than with the cluster that was just a stone’s throw from Watson’s home at the Witherbee Ranger Station.

Crews managed the herculean task of placing artificial cavities in over 500 cluster sites. The Forest Service made preparations for large scale restoration and had teams of people to respond to the needs of the red-cockaded woodpecker. In the first three years following Hugo, crews put in over 1,000 artificial cavities.

The grand experiment

At one point, the number of artificial cavities on the Francis Marion was close to 3,000. Today, there are around 1,400 that are still suitable.

“Everyone who came to help, took that technology back with them and trained others,” Watson said. “This was an experiment on a grand scale, and it worked.”

The technology developed by Copeyon and Allen, applied on the Francis Marion for the first time on a large scale, indeed worked. The installation of artificial cavities has been one of the most successful management techniques developed for the red-cockaded woodpecker and has added greatly to the bird’s recovery.

Watson left the Forest Service in 1998 and worked for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as the Atlantic Coast Joint Venture (ACJV) Coordinator until his retirement in 2022. Before leaving his job with the Forest Service, Watson received the Distinguished Service Award from the Department of Agriculture for his work with red-cockaded woodpeckers in Hugo’s aftermath. But he never really put the woodpeckers behind him. His work with the ACJV focused on restoring and sustaining native bird populations and their habitats throughout the ACJV region. Birds were his life – and still are!

During a 2019 trip back to his stomping grounds at the Witherbee Ranger Station, Watson set out to search for those first artificial cavities that were installed some 30 years before. Joining him were Caroline Causey, then the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources’ (SCDNR) red-cockaded woodpecker Project Leader, and Paula Sisson, a biologist in the Service’s South Carolina Field Office, now retired.

After a few minutes scanning the area with binoculars, he found it – the cluster of trees where the first cavities and inserts went up, still standing like monuments to what Watson calls “the grand experiment”.

Moving in closer, he noticed something hanging off one of the marked trees. With the passage of time, the restrictor plate that keeps larger woodpeckers, squirrels, and other animals from enlarging the hole of the artificial cavity, was sticking out of the tree. Forced outward by the tree’s growth, it was now embedded in the bark that had grown around it. More than just an old cavity tree, this is where the grand experiment started.

Some 33 years ago, it seemed as though all hope had been lost for the red-cockaded woodpecker on the Francis Marion National Forest. But since that time, the birds have recovered there. South Carolina now has over 1,400 clusters of woodpeckers – 563 of those on the Francis Marion. Where there were 1,900 cavity trees on the Francis Marion prior to Hugo, there are 7,174 today.

Two nearby SCDNR properties, Santee Coastal Reserve and Bonneau Ferry, have benefitted from the Francis Marion’s expanding population of red-cockaded woodpeckers. Areas of South Carolina that haven’t seen birds in over four decades now have them moving in. Reintroductions of red-cockaded woodpeckers into suitable habitat within their historic range in places like the ACE Basin south of Charleston continue. And through efforts like the Southern Range Translocation Cooperative, a partnership that began after Hugo, public lands that are saturated with red-cockaded woodpeckers can share their abundance of birds, serving as donor sources for other lands looking to grow their populations.

Silver lining

Since Hugo, an endless barrage of storms has obliterated other forests throughout the range of the red-cockaded woodpecker. But tried and tested, the translocation technique that got its start on the Francis Marion National Forest has been replicated time and again. Hugo truly was a monster storm in many ways, but for that little iconic woodpecker, a silver lining emerged.