Survey Techniques and Protocols

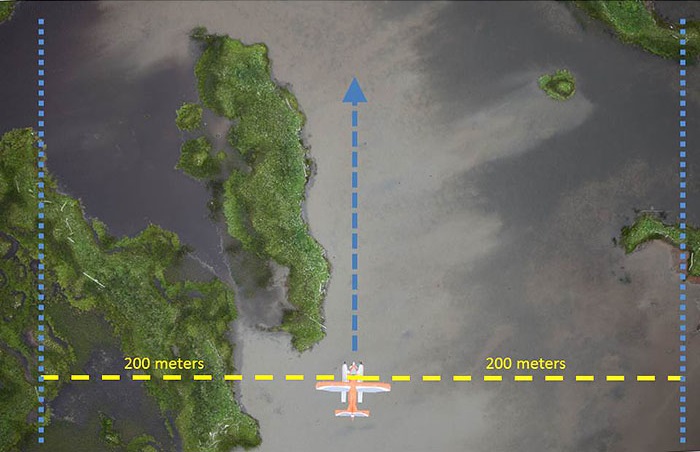

This guide highlights survey techniques and protocols applicable mainly to breeding waterfowl population surveys, but some aspects would apply to other surveys as well. These standard protocols were developed to maximize the comparability of survey results over time. Aerial surveys during the breeding season are typically flown between 100-200 feet above ground level, depending on the survey design, type of aircraft, type of habitat, time of day, and visibility. The low altitude is necessary to identify birds to species. On breeding population transect surveys, each observer counts outward to a predefined width (e.g., 200 meters) on their side of the aircraft. Birds beyond that distance are not counted, and for flocks that transcend the outer boundary of the transect, only those birds inside the boundary are recorded. |

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

The transect width can be gauged using a clinometer and/or by marking the wing strut and window with small pieces of tape that can be used as reference points in level flight at standard altitude. Ground reference marks or landmarks at known distances from a runway or transect centerline may also be used to gauge the position of the outer boundary in flight at survey altitude. In recent years, radar altimeters have been used to maintain proper altitude above ground. Methods for data collection have evolved greatly over time. Early surveys relied on relatively crude maps and landscape features for navigation, with observations recorded on paper, and later on audio recorders. Nowadays, GPS is used for navigation and to maintain transect position, and observations are typically recorded directly to a computer or tablet device and geo-referenced using an onboard GPS and customized computer programs. Breeding population surveys usually provide an index to the number of indicated pairs plus grouped birds, some of which are undoubtedly non-breeders and transient birds. During breeding population surveys, the detection and species identification of ducks is focused mostly on males (drakes). Females (hens) are difficult to identify due to their drab plumage, and many are sitting on nests and not available to be counted. For most duck (and goose) species, computations of indicated pairs account for undetected hens by doubling the observed numbers of drakes (unless drakes are observed in flocks of five or more, as they are then considered to be unpaired). Exceptions to this include some diving ducks (redhead, scaups, ring-necked duck, and ruddy duck) where drakes are not doubled to estimate total indicated birds - these species are known to be late nesters and have significant disproportionately male-biased sex ratios. Within transect boundaries, each observer counts all ducks except lone hens. The following standard definitions for social groups are used in the Breeding Waterfowl Population and Habitat Survey: |

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

Lone hens are not recorded, nor are ducks that cannot be identified to species or genus (e.g., scaup, scoter, merganser).

Distinguishing pairs among small groups of ducks is subjective. The observers must use their best judgement, based on the proximity of males and females, or whether they break into pairs when they take flight. Strive to split groups into distinct pairs and drakes when reasonably possible to do so. For monomorphic birds such as geese, swans, cranes, coots, grebes, and loons, sexes are indistinguishable so it's more difficult to identify pairs. These birds are typically recorded as singles, pairs, or the total number of birds in the group. Generally, if two birds are together, call them a pair. If there are more than two birds, record as a group. Large flocks are usually not encountered during breeding surveys, but they are common in surveys during the non-breeding season. Accurately estimating flock size is difficult. The tendency is to underestimate numbers of birds in flocks; this bias often increases with increasing flock size. The Estimating Flock Size section of this guide provides tips on how to count birds in flocks, as well as a set of flock photos with known numbers of birds that can be used for comparative purposes while in flight |