About Us

The refuge is a haven for plants and animals, supporting Washington's largest and healthiest populations of Oregon coyote-thistle, rosy owl-clover, Kellogg's rush, dwarf rush and long-bearded sego lily. A blend of oak, pine and aspen forests, wetlands, grassy prairies and streams supports a diverse and plentiful wildlife community. The rich habitat diversity sustains thriving populations of migrating waterfowl and songbirds. The rare Oregon spotted frog breeds in wetlands throughout the refuge. Elk are plentiful and frequently seen along refuge roads. And Conboy Lake supports the only breeding population of greater Sandhill cranes in Washington, around 25 pairs.

While the scenery and the plentiful, charismatic wildlife are what draw people in, visitors soon discover that Conboy Lake NWR offers hidden treats, esoteric gems that will keep them returning for years. Elk and deer may be the stars, but visitors soon learn about—and come to appreciate—Oregon spotted frogs, nesting greater Sandhill cranes and the variety of rare plants found on the refuge. A quiet place outside of hunting seasons, solitude is an easily found commodity and greatly appreciated by those coming from bustling metropolitan areas. As a national wildlife refuge national wildlife refuge

A national wildlife refuge is typically a contiguous area of land and water managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for the conservation and, where appropriate, restoration of fish, wildlife and plant resources and their habitats for the benefit of present and future generations of Americans.

Learn more about national wildlife refuge , this living system will satisfy your longing for splendor and serenity, just as it did for the indigenous peoples, explorers, loggers and ranchers who were first drawn to the valley’s plentiful resources.

And history is an important part of Conboy Lake. Native Americans once depended on the area's plentiful resources; in fact, they still do, collecting plants for food and religious purposes. These same resources drew settlers to the area, arriving in the 1870s. One of the early homes, the Whitcomb-Cole Hewn Log House, still stands and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. You are invited to stroll through the house and imagine the struggles these early settlers faced.

Our Mission

The mission of the National Wildlife Refuge System is “To administer a national network of lands and waters for the conservation, management, and where appropriate, restoration of the fish, wildlife, and plant resources and their habitats within the United States for the benefit of present and future generations of Americans.”

Conboy Lake NWR’s mission (refuge purposes) include “use as an inviolate sanctuary . . . for migratory birds,” the “protection of natural resources,” and to “conserve wildlife . . . or plants . . . which are listed as endangered species or threatened species.”

Other Facilities in this Complex

The four refuges that make up the Central Washington National Wildlife Refuge Complex have little in common, other than being in the state of Washington. That makes the Complex a wonderfully diverse blend of habitats, species, and recreational opportunities. There’s something to be found by everyone that will pique their interest or pull them into the landscape. A geology buff? Visit Columbia National Wildlife Refuge, carved by the great floods of the last ice age. Need a scenic landscape to paint or simply unwind in? Conboy Lake is the spot. Interested in our history? The Hanford Reach National Monument is the place to investigate. Want to add to your birding life list? Check the spring and fall migrations through Toppenish.

Columbia National Wildlife Refuge

Columbia National Wildlife Refuge is a scenic mixture of rugged cliffs, canyons, lakes, grasslands, and sagebrush sagebrush

The western United States’ sagebrush country encompasses over 175 million acres of public and private lands. The sagebrush landscape provides many benefits to our rural economies and communities, and it serves as crucial habitat for a diversity of wildlife, including the iconic greater sage-grouse and over 350 other species.

Learn more about sagebrush . The mix of lakes, carved by unimaginable floods during the last ice age, and surrounding irrigated croplands, a result Grand Coulee Dam and the Columbia Basin Irrigation Project, combined with generally mild winters and the protection provided by the refuge, attracts large numbers of migrating and wintering mallards, Canada geese, tundra swans, and other waterfowl. As winter turns to spring and frozen lakes begin to thaw, additional waterfowl return in great numbers. The largest concentrations of ducks, geese, and lesser Sandhill cranes arrive on the refuge in March and April, at times numbering over 75,000 individuals. The arrival of the cranes and other waterfowl draw visitors from all over the region, centering around the annual Othello Sandhill Crane Festival.

Hanford Reach National Monument

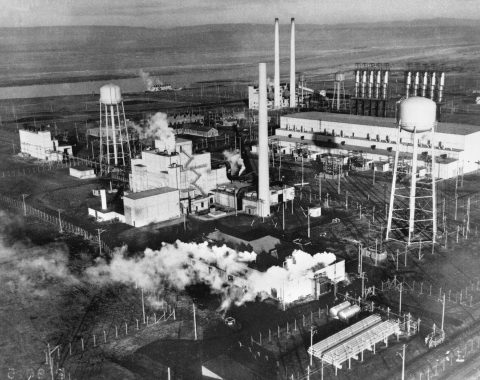

Thousands of acres of land along the Hanford Reach of the Columbia River and the Saddle Mountain National Wildlife Refuge became the Hanford Reach National Monument in 2000 to protect rare plants, wildlife, and remnants of human history. The 196,000-acre Monument is open, treeless country punctuated by steep rolling hills and canyons. Since 1943, what are now Monument lands have been a safe haven for important and increasingly scarce natural and cultural resources. The lands were allowed to remain wild because they served as a security buffer for the top-secret Manhattan Project during World War II, which produced plutonium for atomic weapons. With limited development and grazing, native plants and animals thrived, and a diverse archaeological record has been preserved. The Monument supports 725 vascular plant species—at least 47 of which are species of conservation concern—42 species of mammals, more than 200 species of birds, 9 reptile and 4 amphibian species, 45 species of fish, and over 1,600 species of insects.

Toppenish National Wildlife Refuge

Toppenish National Wildlife Refuge, established in 1964, is an important link in the chain of feeding and resting areas for waterfowl and other migratory birds using the Pacific Flyway. Although Toppenish was established primarily for migratory waterfowl, many other migratory and resident wildlife species live here, such as American bitterns, peregrine falcons, badgers and beavers. The refuge is a broad collection of habitats supporting a diversity of species. Natural wetlands, such as sloughs and oxbows, and artificial wetlands are flanked by riparian riparian

Definition of riparian habitat or riparian areas.

Learn more about riparian areas. Many species of migratory waterfowl and nongame birds, such as Virginia rails and savannah sparrows, use the wetlands for feeding and nesting activities. Native shrub-steppe—characterized by greasewood, Wyoming big sage, rabbitbrushes, bitterbrush, and native bunchgrasses, such as Great Basin wildrye, Indian ricegrass, Idaho fescue, and Sandberg bluegrass—once covered the upland areas. Loggerhead shrikes, long-billed curlews, California quail, Brewer’s and sage sparrows, and sage thrashers are only some of the animals that use the shrub-steppe. This diverse combination of habitats is a natural magnet to migratory and resident wildlife, alike.