On Feb.8, 2023, the Bureau of Land Management Alaska and the government of Saga City, Japan formalized a sister site relationship between Qupałuk (KU-pah-luck), Alaska and Higashiyoka-higata, Japan. This is their story…

Dun Dun, Dunlin

Back before technology changed how we study animal movements, we could only guess the specifics of bird migration routes, how different populations separate during their migrations, or how they stay together. For a long time, this guessing game characterized scientists’ understanding of Dunlin (Calidris alpina), a small, plump, relatively long-billed shorebird species that breeds throughout the circumpolar arctic and northern temperate regions.

For centuries, this species has called Alaska home, breeding in the summer and staging in the fall, before leaving the state for their wintering grounds.

But the Dunlin story isn’t so simple — decades of collaborative research, culminating in the recently-forged partnership between Alaska and Japan, have revealed that there isn’t just one Dunlin, but two, and the northern breeding subspecies travel across the ocean, with most landing in Japan to spend their winter.

"For a long time, we didn’t realize there were two populations or two ‘subspecies,’ we thought there was only one," said Rick Lanctot, migratory bird biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) in Anchorage, Alaska. “One subspecies breeds in Western Alaska — Calidris alpina pacifica, and one breeds on the North Slope — Calidris alpina arcticola. But both populations merge in the fall, staging together in central-western Alaska before making their fall journeys to their wintering grounds."

The story of this revelation begins in the 1970s…

The First Bands

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) retired biologist Bob Gill first led Dunlin banding efforts in Alaska at their staging grounds on the Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge in the 1970s. Though, at the time, they weren’t using the metal leg bands we use today.

“I remember putting picric acid on some of the birds’ feathers, which turns them yellow,” Lanctot recalled. “That was a way for us to try to see which individuals we captured and how they were moving along the Yukon Delta coast.”

As bird banding evolved, the biologists were able to source metal bands and colored leg flags. With individual birds sporting easier to see leg flags, sighting reports first came in from Asia. Meanwhile, other birds were seen along the Pacific Coast of North America.

At first, there was confusion whether the birds that flew to Asia had done so on purpose or had unknowingly been blown off their migratory path. Decades of collaborative studies between the USFWS, Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Japanese scientists, and the USGS have improved our understanding of Dunlin genetics, morphology, and migration tracking.

Now scientists are certain that there are two different Dunlin subspecies breeding in Alaska. Their collaboration also revealed the two subspecies migrate to two different wintering areas.

Why Dunlin?

This suspicion — that Dunlin migrate from Alaska to two distinct wintering areas — was furthered by Rick Lanctot in the early 2000s when he began a long-term research project on arcticola Dunlin in Utqiaġvik (formally Barrow) and throughout the Arctic coastal plain. Lanctot chose to work with Dunlin for a few reasons and describes the qualities that make them ideal subjects.

“They are a very tolerant species. You can catch them repeatedly and monitor them very easily. When 50% come back year after year, it makes them easy to study. Their attachment to the site is very strong.”

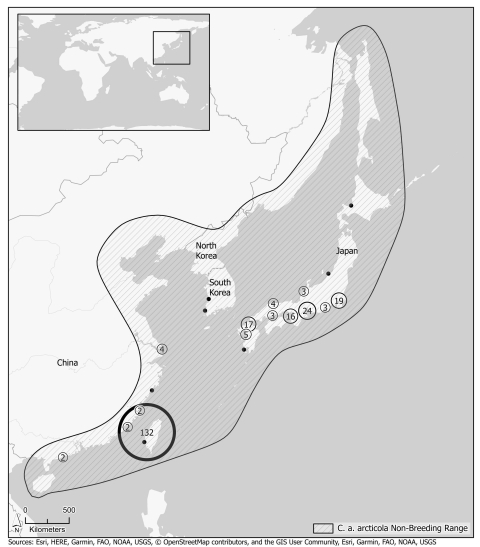

Lanctot and the team of researchers and graduate students have banded thousands of Dunlin across the North Slope of Alaska, and none of those birds have been reported along the Pacific Coast of North America. This data made the case that the North Slope breeders all migrate to east Asia for the winter.

Let’s Count ‘Em

In 2001, A Canada-U.S. shorebird committee developed and implemented the first Program for Regional and International Shorebird Monitoring, or PRISM, throughout Alaska and Canadian Arctic and boreal areas. According to Lanctot, PRISM is a hemisphere-wide effort that includes arctic breeding, migration, and winter efforts to estimate shorebird numbers.

“Unlike waterfowl (ducks, geese, and swans) whose populations have been estimated every year since 1955, North American shorebird estimates have only been published once, though a second is forthcoming.”

In 2012, USFWS biologists Jim Johnson, Rick Lanctot, and Brad Andres (retired) published a paper in collaboration with Manomet, Inc. entitled, “Shorebirds Breed in Unusually High Densities in the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area, Alaska”. This was the first study to estimate the population size and density of shorebirds breeding in the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area, located within the North Slope and administered by the BLM.

They found that the greatest densities of breeding shorebirds occurred immediately around Teshekpuk Lake. The area supported more than 10% of the biogeographic populations of Black-Bellied Plover (Pluvialis squatarola), Semipalmated Sandpiper (Calidris pusilla), and Dunlin (C. a. alpina)

Results from these surveys paved the way for the discovery of another important site adjacent to Teshekpuk Lake: Qupałuk, which is Iñupiat for ‘small shorebird’.

Qupałuk is a relatively small (52,000-acre) area of land just northeast of Teshekpuk Lake. Though the Teshekpuk Lake area is of known importance for molting geese, polar bears, caribou, and Alaska’s two listed bird species: Steller’s and Spectacled Eiders. The area of Qupałuk was found to host ~30,000 breeding migratory waterbirds and ~6,500 arcticola Dunlin, or greater than 1% of the population of Dunlin around the world.

This significant discovery was the first step in bringing attention to the area of Qupałuk, its importance to Dunlin, and its significance nationally and internationally.

The Partnerships

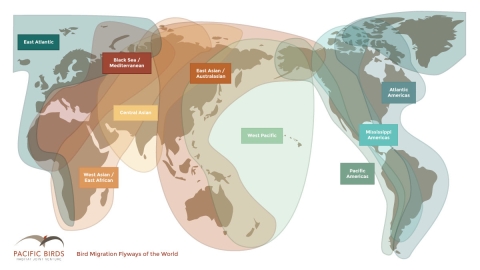

The East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership (EAAFP) was formed on Nov. 6, 2006, during the World Summit on Sustainable Development. This partnership is a voluntary initiative, which aims to protect migratory waterbirds that use the EAAF, their habitat along the EAAF, and the livelihoods of people that depend on these birds, such as Indigenous peoples who live subsistence lifestyles.

The flyway framework promotes dialogue, cooperation, and collaboration between a range of stakeholders — from governments to community groups and local people, to conserve migratory waterbirds and their habitats, considering both people and the biodiversity of the flyway.

In 2013, the EAAFP held a meeting in Anchorage. During that meeting, the Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge was officially recognized as the first EAAFP Network Site in Alaska. The EAAFP Flyway Site Network ensures these places are sustainably and holistically managed. The management goals are to support the long-term survival of migratory waterbirds within the flyway and the people whose livelihoods depend on them.

A few years later, in 2015, a new Flyway Network Site was in the works: Qupałuk, the productive area located within BLM-administered land. Casey Burns, newly hired wildlife program lead for BLM Alaska, was instrumental in moving this process forward.

“Within a few months of me starting my position, Rick reached out about getting Qupałuk recognized as an EAAFP Flyway Network Site,” Burns recalled. “After some internal scoping to make sure we had support, we determined we could move forward. The next step was to make sure we had Indigenous support.”

Lanctot and Burns set up several in-person and online meetings with Qupałuk stakeholders, including several Indigenous groups. Local Indigenous leaders from the Iñupiat Community of the Arctic Slope (ICAS) voted their approval, which solidified the blessing from this important group.

"The EAAFP Network Sites are very focused on local people,” Burns pointed out. "That’s a major component. A big part of Qupałuk being recognized is that it continues to acknowledge the value of the area for subsistence harvest."

The next step after getting Indigenous support was to get the site nominated and accepted by the EAAFP.

In January 2017, the site was officially accepted into the EAAFP Flyway Site Network at the EAAFP 9th Meeting of the Partners in Singapore. Qupałuk is the first flyway site for any flyway network on BLM-managed lands and only the second EAAFP Flyway Network Site in the United States.

Sister, Sister

“Immediately upon Qupałuk becoming a Flyway Network Site, we were already thinking about partnering with another Flyway Network site to make it a ‘sister site’. We had some preliminary discussions with Japan, and Saga City had come up as a good candidate for sisterhood,” Burns recounted the progression.

After six years of hard work and collaboration, persistence paid off. On February 8th, 2023 the formal ceremony was held in Saga City, Japan to officially commemorate the two EAAFP sites — Higashiyoka-higata, Japan, and Qupałuk, Alaska as sister sites.

Both sites provide important habitat for migratory waterbirds, especially Dunlin. This partnership will help conserve habitat for Dunlin and other migratory birds on an international scale, while also highlighting the continued collaboration of these two important sites for avian research and conservation.

Japan has many Dunlin; it is its most abundant shorebird species there during the winter. The Higashiyoka-higata Flyway Network Site in Saga City supports the highest number of wintering arcticola Dunlin in Japan, all of which breed in Arctic Alaska, including at the Qupałuk Flyway Network Site. This subspecies of Dunlin is in decline, it is a USFWS focal species, and a species of concern throughout the flyway.

The Higashiyoka-higata site is a 539-acre tidal mudflat, the largest remaining in Japan, located on the northern shore of the Ariake Sea. The site regularly supports 1% of the EAAF population of the Endangered Black-faced Spoonbill and Vulnerable Saunders’s Gull, and more than 10,000 migratory waterbirds visit the site annually.

Higashiyoka-higata is also a Ramsar Site since 2015, a wetland site designated to be of international importance under the Ramsar Convention, known as “The Convention on Wetlands”, an intergovernmental environmental treaty established by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The site is important for traditional knowledge, techniques, and food security, and who’s traditions have been retained and passed on for many generations.

The EAAFP Flyway Site Network was established to ensure a network of internationally important sites are sustainably managed to support the long-term survival of migratory waterbirds within the EAAF. To date, there are 152 Flyway Network Sites in the EAAFP. Under this network, the EAAFP Sister Site program offers a mechanism for Flyway Network Sites to collaborate closely on monitoring and research, capacity-building, sharing and exchanging information and experiences.

In Alaska we are shared stewards of world renowned natural resources and our nation’s last true wild places. Our hope is that each generation has the opportunity to live with, live from, discover and enjoy the wildness of this awe-inspiring land and the people who love and depend on it.

Follow us: Facebook Twitter Apple Podcasts