In the arid wilds of the Chihuahuan Desert’s northern range in southern New Mexico, an icon of conservation dwells, deep in a hole in the ground, defying human standards of time. Her name is Gertie, and she is an endangered Bolson tortoise of mysterious age and endearing demeanor. Gertie's journey, from her origin in the Mexican wilderness to her vital role in the return of her species to the United States, chronicles a multi-generational conservation effort.

What’s known of Gertie began in 1971, when imperiled species protection laws were in their infancy, and the Bolson tortoise was still a newcomer to science. The species’ common name comes from its home range in the Bolson de Mapimi region at the convergence of the Mexican states of Chihuahua, Durango and Coahuila. Bolson tortoises are the largest of the six North American tortoise species. In past millennia, Gertie's forebears dug 15-meter-long burrows northeast up to Kansas, down to south-central Mexico, and west to the Pacific, according to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Biologist Shawn Sartorius.

“After the Pleistocene epoch ended about 12,000 years ago, their range collapsed to what it is now,” said Sartorius, who is the New Mexico Ecological Services Field Office Supervisor for the Service. “We don't know precisely why that happened. It could have been climate change, human predation, or a combination of factors.”

According to Sartorius, Fossil and archeological findings indicates that extinct giant tortoise species as well as Bolson tortoises were a food source for humans toward the end of the last Ice Age. Since then, the Bolson tortoise’s range shrank to the Bolson de Mapimi, which is an inward flowing basin without any naturally occurring surface water. This made it unfit for human habitation. With the implementation of mechanical well-drilling, people began populating that region. Remaining Bolson tortoise populations are imperiled due to collection, habitat loss, and climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change .

A Giant Discovery

In the late 1950s, visiting scientists saw chickens eating from a huge tortoise shell: a species they didn’t recognize. It was described scientifically by biologist Dr. John Legler in 1959 and scientifically named Gopherus flavomarginatus for its shell’s yellow margins. Also called Mexican giant tortoise, locals in the Bolson region call it tortuga grande, according to Bolson tortoise expert Dr. Chris Wiese.

With the help of Mexican conservationists, American southwest herpetology icon Dr. David J. Morafka led researchers to the Bolson de Mapimi. They began studying the biology and ecology of the tortoise and transported individuals to the U.S., including an adult female tortoise to a herpetologist working at the Appleton-Whittell Research Ranch near Tucson, Arizona, said Dr. Wiese.

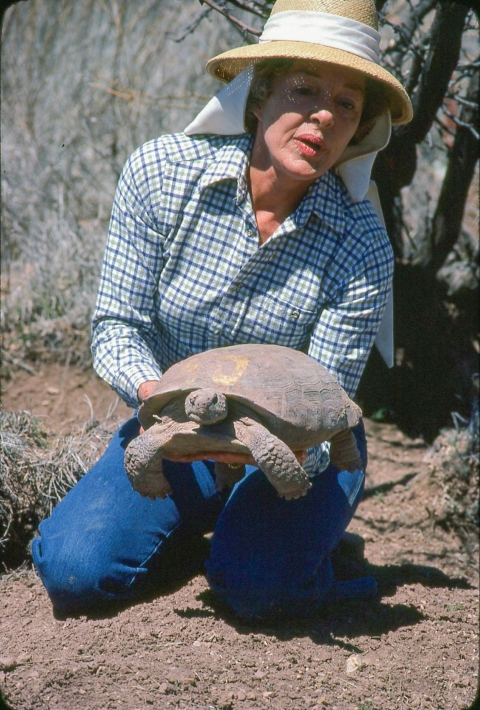

This female tortoise was placed in an enclosure near the home of Ariel Appleton, who owned and resided on the ranch, said Dr. Wiese. Watching the tortoise from her porch, Ariel became enamored, formed a bond and named her Gertie. With the arrival of more tortoises as part of a University of Arizona study, Gertie mated and laid eggs, becoming the first of her species to breed in the U.S.

According to Dr. Wiese, there’s no known method for aging adult Bolson tortoises, and their age of sexual maturity remains undocumented. Experts can only assume it’s on par with other Gopherus tortoises, which is 15-20 years. Dr. Wiese recently observed a 16-year-old female tortoise mating, but she has yet to lay eggs, indicating she’s not yet mature.

Gertie was fully mature and a large specimen in 1971, meaning she was at least 30, and possibly much older, according to Sartorius. She’s laid eggs almost every year since then and shows no signs of slowing down, indicating she's still in her prime breeding years.

“The scientists working with the tortoises had to move on, and were unable to take the Bolsons with them, so my mother inherited them,” said Ariel’s daughter Lynnie Appleton, a retired veterinary technician. She grew up around many animals on that land when it was a cattle ranch. Her parents devoted it to ecosystem research in 1969.

While the Appleton Ranch wasn’t the only U.S. organization to receive Bolson tortoises, Ariel was the first to successfully raise hatchlings, according to Dr. Wiese.

“She wasn't a scientist, but she was an animal person,” remembered Lynnie. “One of the most amazing things I learned from her is that by observing animals, they teach you. If it took four hours for a tortoise to show what natural forage they liked, she would watch them for four hours. She understood tortoise time. Their pace is much slower than ours.”

Tortoise Time

In Ariel Appleton’s decades with the Bolsons, she formed bonds with and named several individuals, and helped build upon the base of knowledge. As a non-scientist, Ariel often relied on experts, including Tucson Veterinarian Dr. Jim Jarchow. Ariel brought her pets to him. He had worked as a zoo reptile keeper, and, intrigued with this new species, began visiting the ranch regularly.

For a herpetologist, the Bolson tortoise is nothing short of a natural wonder. Its physiology was and still is mysterious. Despite the males possibly having the highest testosterone concentrations of any vertebrate, male and female Bolsons are basically indistinguishable. Dr. Jarchow put his practice on pause to travel to Mexico to study Bolson tortoises with Dr. Morafka.

“Gertie was a very healthy tortoise,” Dr. Jarchow remembered. “You become very attached to her and she to you while working with her over the years. It’s like having a dog with a shell.”

Dr. Jarchow eventually returned to his practice and continued to visit the Appleton ranch. In 1979 the tortoise gained endangered species protections. Dr. Jarchow has since retired but remains valued in the Bolson tortoise community. In 2004, both Dr. Morafka and Ariel Appleton passed away.

Former Secretary of the Interior Stuart Udall wrote to Ariel, "I have known dedicated conservationists in my time who had dreams, but frankly few of them ever live to see big dreams come true. You are one of that select group, and I want you to know how much I admire what you have done with The Research Ranch."

Team Turner

Meanwhile, over in New Mexico in 2004, a group of wildlife biologists met, led by herpetologist Dr. Harry Greene, at Ted Turner’s Ladder Ranch for a writing workshop. Their topic considered a theory that humans hunted many North American megafauna species to extinction. Their goal was to publish a paper on the ecological value of introducing relatives of those extinct megafauna into the wilds of North America.

Various wildlife biology experts made cases for replacement species in their field of study that could fill a missing ecological niche (i.e. Indian elephants for mammoths, African cheetahs for the extinct American ones.) Harry, as a herpetologist, chose the Bolson tortoise to replace extinct mega tortoises. This was an ideal option, because they aren’t extinct, and they once inhabited a large swath of the U.S.

Botanist Jane Bock, who worked with the Appleton Research Ranch, was at that meeting. Prior to Harry pitching the Bolson, Jane approached him, saying “‘We have a problem, and you’re a herpetologist. Ariel Appleton just died, and her family wants to do something creative with her Bolson tortoises.’ I couldn't believe what I was hearing,” remembered Dr. Greene.

The late Turner Endangered Species Fund (TESF) biologist Joe Truett was at the meeting as well. “Joe was standing next to me. He then turned to me with this huge grin and said, ‘Ted really loves turtles,’” recounted Dr. Greene.

Turner biologists began working with the Research Ranch, going through a careful process to transport the group of Bolson tortoises to Turner facilities in New Mexico.

During that process, the Turner organization reached out to a colleague of the late Dr. Morafka, desert tortoise expert Scott Hillard. Biologist Dr. Chris Wiese, who is Hillard’s wife, also joined. They picked up where Ariel Appleton left off, raising tortoises and building a basis for a U.S. recovery program. They also became enamored with Gertie.

“She captures the imagination of anyone who sees her,” commented Dr. Wiese. “Most people don’t know they are such large tortoises native to this desert, and when they hold her for the first time it seems to have the same effect on everyone. They get this huge grin.”

“She dances,” added Hillard.

Continue Reading on to Part Two: Operation Recovery

ESA@50 – December 28, 2023, marked the 50th Anniversary of the Endangered Species Act of 1973. Recovery of species like the Bolson tortoise is complex and difficult work, often requiring substantial time and resources. Species today face ongoing threats like habitat loss as well as new threats like climate change and wildlife trafficking. We have a continued commitment as a nation to protect imperiled species.

Today, hundreds of species are stable or improving thanks to management actions of tribes, federal agencies, state and local governments, conservation organizations and private citizens. Our partners share a commitment to build on our accomplishments and expand innovative initiatives to further this mission in the future.