By Jan Peterson, for the Pacific Region of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

In just a decade, the Salmon SuperHwy project is already more than halfway to its goal of opening 180 miles of cold, clean water along Oregon’s North Coast for spawning anadromous fish such as coho, Chinook, steelhead and cutthroat trout and lamprey. Once complete, the project will have restored 95% of historic habitat connectivity.

The partnership has brought together private landowners, governmental and nongovernmental groups to complete projects that give the fish access to the cold habitat they need to survive while resolving a host of issues for humans. These issues include chronic flooding and antiquated infrastructure.

The Salmon SuperHwy has removed 47 of 93 barriers identified as high priority, which has opened 124 miles of upstream habitat. With the easiest and least expensive projects completed, the group now turns its efforts to some of the larger projects, including two in Tillamook County due to be complete by October.

“We’re now at the point where we’re working harder,” says Liz Ransom, Salmon SuperHwy director at Trout Unlimited. “We’ve hit all the projects that would open many miles at once.”

The partnership allows a small county public works department like Tillamook’s to avert catastrophic failures of water crossings while creating jobs in the county that has a population of about 27,500, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Overall, the Salmon SuperHwy has created 246 jobs since it launched.

“There’s no chance — no chance — that in the budget a small county office has that we could pursue even one of these projects much less the list we’ve completed if it were not for our federal partners bringing infrastructure dollars at the levels they continue to bring in for us,” says Ron Newton, who works with the Tillamook County Public Works Department and is engineering liaison to the Salmon SuperHwy.

The jobs created by Salmon SuperHwy projects aren’t just seasonal. Newton says he’s been a member of the collaborative’s executive team since the beginning. In that time, he’s seen the impact these projects have on the overall community.

“These projects are big enough, there’s so much time and money involved, the impact to the community goes well beyond having a sound roadway,” he says. “It takes a significant input of local skilled labor, local skilled contractors. It blows out through the rest of the economy.”

When he started with the county 15 years ago, Newton says, there were maybe three local contractors that could reliably deliver public infrastructure-quality work. “Today, there’s a full half dozen and they’re all busy all the time, so we are at a point where we have to plan to get into their schedule.

“That growth can be directly tied back to the 20-plus bridges that we’ve built in the last 15 years.”

Culvert Failures Inevitable

Newton says fish-passage problems proliferated in the 1950s with the introduction of corrugated steel. “The thinking was, what a wonderful boon because now these aging timbers on all these rural county timber bridges that are rotting can be taken out. We can put this steel pipe in, build a road over it and walk away,” Newton says.

This practice may have seemed a genius inexpensive fix at first blush, but as the decades rolled on, the costs approached devastating levels. This construction method introduced a host of problems including blocking fish access to vital cold water upstream, rocks and large tree debris pummeling and clogging the culverts for years on end, the entire streambed washing out and rust inevitably having its way with the culvert.

Another way a culvert can create passage problems is by becoming perched, meaning the streambed below is washed away leaving the culvert suspended above the stream and out of the reach of jumping fish. The culvert may also be too small for fish to navigate or becomes blocked with debris.

“They’re typically planned for a 40- to 50-year lifespan,” Newton says of culvert crossings. “We’re in the range of 30 to 40 years beyond their anticipated lifespan and many of them are very close to failure. If we can get ahead of these and replace them before they approach catastrophic failure, then what we don’t have is the whole roadbed and the steel and the whole mess washing down the stream and cutting the road in half so nobody can get past that crossing.”

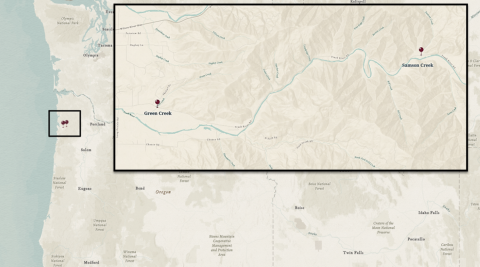

The projects under way now are at the Green and Samson creeks, tributaries to the Trask River. “The Green Creek crossing is critical,” Newton says, explaining it’s at the western end of a canyon and is the only access to an area filled with industrial timber operations, recreation opportunities, agriculture and more than 100 residential properties. “If Green Creek were allowed to fail, every one of those individual components of the economy would be negatively impacted.”

Newton says the culvert had already deteriorated to the point where the public works department had to keep excavation equipment parked there and staffed overnight during heavy rains to clear debris as it piled up to prevent flooding or a catastrophic failure. “Once a culvert gets to that point, it starts collapsing. Time is not your friend anymore,” he says.

The crossing on Samson Creek is in similar shape.

Because of their proximity, a single contractor was hired to do both, which Newton and Ransom say saved a considerable amount of money and added efficiency.

The projects will remove those culverts and replace them with approximately 35-foot concrete bridges over natural streambeds, making a world of difference for wildlife and humans.

“We literally have not had a catastrophic failure in over 10 years now,” Newton says. If it were not for the combination of funding and technical assistance we receive through the Salmon SuperHwy program, we would be in a constant triage mode. There’s just no other way to look at it.”

Partnerships Vital to Success

Trout Unlimited’s Ransom says while she may be Salmon SuperHwy program director, she’s only one part of the solution. There’s no way any of these projects could have happened without the many partners and variety of funding sources involved — from private to federal, she says.

Leah Tai, a hydrologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, says the technical support the Service provides along with funding it secured through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Bipartisan Infrastructure Law

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) is a once-in-a-generation investment in the nation’s infrastructure and economic competitiveness. We were directly appropriated $455 million over five years in BIL funds for programs related to the President’s America the Beautiful initiative.

Learn more about Bipartisan Infrastructure Law is crucial for these projects to move forward.

“There are three permanent staff on the Tillamook engineering team, and they’re in charge of everything from fish passage fish passage

Fish passage is the ability of fish or other aquatic species to move freely throughout their life to find food, reproduce, and complete their natural migration cycles. Millions of barriers to fish passage across the country are fragmenting habitat and leading to species declines. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's National Fish Passage Program is working to reconnect watersheds to benefit both wildlife and people.

Learn more about fish passage to plowing the roads. They have such a crazy array of tasks they have to get done,” Tai says. “They don’t have the resources and capital to tackle that on their own.”

Ransom says investing in these projects is an investment in not only the survival of species including Endangered Species Act-listed coho, but the whole of the region. “It’s an investment for the land, for the forest — everything out here is dependent on these fish. They provide the ocean nutrients to the forest as well as to our economy out here. They need to have safe and happy habitat,” she says.

Jacob Jesionek, Salmon SuperHwy’s restoration project manager, says seeing the results of these projects is incredibly gratifying. “We took this habitat away from them. We blocked it off with culverts and they’re really suffering. It’s really cool to see there are now fish spawning above these culverts where we put in bridges,” Jesionek says.

Salmon SuperHwy At a Glance

2023 Goals

- Complete four projects to reconnect 4.5 miles of habitat

- Support the return of six species of ocean-going fish species to historic habitat

- $2 million will be leveraged

- Secure a funding package that will propel SSH toward the finish line

- Partner with specific landowners to put remaining priority projects in motion.

2022 and Overall Successes

- Four projects completed/barriers removed for a total of 47 of 93

- Nine miles of habitat reconnected for a total of more than 124 miles, more than two-thirds of the way to SSH’s goal of 180 miles

- Six species of ocean-going fish restored to historic habitat

- $1.6 million in funding leveraged for a total of $17.6 million so far

- 22 jobs created for a total of 246

- Landowners united with local, state and federal partners to meet goals

Partners:

Local: Tillamook County; Tillamook Estuaries Partnership; Tillamook County Creamery Association; Tillamook Bay Watershed Council; Nestucca, Neskowin and Sand Lake Watersheds Council.

State: Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Oregon Department of Forestry, Oregon Department of Transportation, Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board, Oregon Fish Passage Task Force

Federal: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, Natural Resources Conservation Service

Non-governmental: Trout Unlimited

(Source: Salmon SuperHwy annual report)

Our public lands, like our roads and bridges, require strategic investments and management to protect the fish and wildlife that is so important to the American public. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law provides $91 million to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service over the next five years to support our natural infrastructure and protect these valuable resources.

The Alaska, Pacific, and Pacific Southwest Regions of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service have collaborated to tell stories of climate-related challenges, adaptations, and outlook for hope for Pacific salmon species from multiple perspectives. Learn more about the efforts of the Service, Tribes and other partners to help Pacific salmon overcome the challenges they face due to climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change : New Challenges in the Struggle to Save Pacific Salmon