Some birds make long journeys throughout the year while others seem to stay in your backyard. One way to better understand their behaviors and distribution is through banding and marking birds with individual identifiers. These uniquely colored or coded “bird bracelets” can be resighted and reported by anyone. The banded representatives give insight to what the whole population is up to year-round. Banding projects are especially useful for threatened and endangered species like the red knot to help inform conservation decisions.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Geological Survey, Audubon Florida, Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission and local bird researchers came together on Feb. 1, 2022 and banded 126 red knots at Fort De Soto Park in Pinellas County, Florida. This project was led by the Coastal Program Coordinator, Kevin Kalasz and Dr. Abby Powell, Unit Leader of the USGS Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Unit. Behind them was a team of experienced banders and knowledgeable biologists who all helped safely execute the project.

Red knots – who are they?

Red knots are a species of shorebird that breeds in the Arctic tundra and spends the winter in South America, Brazil, throughout the Caribbean and along the Gulf Coast. Red knots make one of the longest migrations and can cover up to 1,500 miles or more without stopping. To do this, they go through dramatic changes including reducing their digestive system and burning fat stores and even muscle. Refueling at Delaware Bay, a horseshoe crab spawning hotspot, is a crucial step in completing their migration to breeding grounds. However, research is telling us not all red knots that spend the winter in Florida stop in Delaware Bay on their migrations to and from the Arctic. These scientists are trying to better understand their movements and habitat use.

Like other shorebirds, the red knot is threatened by coastal development, but the added pressure of overharvested horseshoe crabs has caused a rapid decline since the early 2000’s. Poorly nourished birds struggle to make the rest of the journey to the Arctic to breed. In order to recover the species, we need to better understand and protect the juvenile stage of the red knot life cycle. Understanding where these birds are and how they move around during their first two years is critical to protecting the habitats they need. Little is known about the movements of juvenile red knots, many of which spend the winter (and sometimes summer) in Florida. Tracking red knots through band and flag resightings and transmitters provides data that is used to better inform conservation efforts and increase the survival of the species.

The capture – Base camp, Twinkle Team and the occasional sanderling

There are multiple techniques for rounding up and capturing birds. For this project, a cannon net was deployed to capture as many red knots as possible in one attempt. But let’s back up and talk about twinkling. Twinkling is a term used to describe the action of slowly walking birds within range of the net. On this day, the aptly named “Twinkle Team” walked a flock of around 300 red knots along the shore gently enough to not cause them to fly away.

When the flock was within range, the net was fired. The rest of the banding team at base camp, located higher on the beach and a safe distance from the cannon net, ran to the red knots with supplies. The netted birds were covered with lightweight material to calm them while they were being collected and placed in boxes. The occasional captured sanderling and black-bellied plover were released while already banded red knots were kept for recapture data collection.

Once the red knots were safely situated in the shade, it was time for banding. The banding group was split into two teams: flagging and processing. The flagging team was responsible for putting uniquely coded flags on the upper left leg of each bird. The green color of the flag indicates that the bird was captured in the U.S.

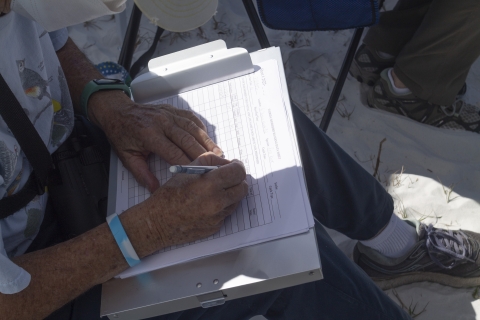

After being flagged, the bird was moved on to processing where they received a metal federal band on the lower right leg and had measurements taken. The wing length, back of head to tip of bill length, bill length and weight were recorded on data sheets with corresponding flag and federal band codes.

Recaptured birds that were already flagged were noted on the data sheets and all the same measurements were taken providing a rich history of the bird and its condition over time. Recapture data provides more information than the typical band or flag resighting that can be compared to measurements that were previously taken of that bird.

Tracking with transmitters

After processing, adult birds were released to join the rest of the flock at the shoreline while a portion of the juveniles were fitted with transmitters.

Attaching transmitters to juveniles, in addition to coded leg flags, will provide insight into where they spend their time during the first two years.

“It is necessary to better understand the juvenile life stage,” Powell said.

The primary goal of this project, identified by Powell, is to develop the information needed to make good conservation and management decisions on the juvenile life stage of red knots. The information collected from the transmitters will help determine what areas to keep an eye on during their first two years to develop management recommendations.

One type of transmitter attached to the juvenile red knots were nanotags. These tiny, light-weight transmitters rely on a network of towers to pick up the emitted signal. Motus towers are specifically used to track small flying animals that have been fitted with those nanotags. GPS PinPoint tags were also fitted on some of the juvenile red knots. This type of tag relies on satellites to retrieve the location information. Using transmitters to track birds provides location updates without having to rely on band and flag resightings.

If you see a banded bird, you can submit your data to the Bird Banding Laboratory or to bandedbirds.org. Each resighting provides valuable information used to develop management and conservation actions.