I’m smitten by yellow rails. If you’ve ever had a close encounter with a yellow rail, you’d be smitten too. Ever since I was introduced to them in 2005 – by one of the World’s experts on yellow rails (and good friend and neighbor), Ken Popper – I’ve been working on understanding these cute little birds.

What’s a yellow rail, you ask?

They are about the size of robin, but skinnier and with short tails; they are stealthy and shy (except when they’re not – read on); they are streaked with dull yellow and dark brown, dappled with white flecks, like water-splashed old grass and the sedge that it lives among; and they are much more often heard than seen. Even hearing one takes special effort - you have to know where to go and what to expect from their unique tic-tic-tic call that sounds like rocks clicking together.

Listen to a yellow rail's call at xeno-canto at this link: yellow rail call

Nearly all the yellow rails in the world breed in freshwater marshes and sedge bogs across the Canadian prairies and taiga wetlands, dipping into the upper Midwest and northeastern states. The birds spend the winter in marshes, wet grassy fields, and rice crops along the Gulf of Mexico, predominantly in Texas and Louisiana.

But there is a single (as far as we know) geographic outlier, a very small population that breeds in a handful of locations from northeastern California to south-central Oregon. Most of these birds breed only at Klamath Marsh National Wildlife Refuge.

Scientists first described this western outpost of yellow rails in 1926, then “rediscovered” them in 1982. We will never know how abundant these western yellow rails were historically, but there are only about 200 pairs in the west according to the most recent census.

Whether in the Midwest, Canada, or Oregon, a yellow rail has a short list of needs in the summer: clean, fresh water that’s 2-4 inches deep, and a sea of relatively dense sedges and grasses that aren’t more than 2 or 3 feet high to hide in. They eat small aquatic insects, mollusks, and seeds they find as they slip through the sedge.

The other thing to know about yellow rails is that males call from their marshy territories for much of the night through mid-summer. Their rhythmic calling, tic-tic, tic-tic-tic carries across the marsh in the dead of night as males protect their watery plot of sedge and woo local females. They reveal their presence to the world only after dark, and that, my friends, is how one counts the otherwise very secretive yellow rail.

More Than One Bird Brain: The Western Yellow Rail Working Group

For the past couple of summers, a small team representing agencies, universities, conservation organizations, and retired professionals has gathered at the refuge to count what remains of the western population of yellow rails. The focus of the Western Yellow Rail Working Group is to census the yellow rail population in and around Klamath Marsh. We want to know how many there are, compare our tally to previous years, and note exactly where they are on the refuge, in the hopes of assuring the rails have what they need to survive.

This past summer, I biked down to the refuge from Portland to join my colleagues for a census. Donning the dress of the marsh (hip-boots or chest waders) we transected the wet sedge meadows of the refuge in teams of two or three, noted approximated distances and directions of calling birds, and derived an estimate of their numbers. It was occasionally challenging plowing through a thick patch of dense and tall cattail or bulrush on the way to a patch of better habitat and a calling bird. But it is a labor of love, and at this point the best method to estimate numbers and population trends of yellow rails in the west.

The experience of spending all night in the marsh is unique, and because it’s dark, it’s a magical, aural experience. At any given moment, one can hear the howl of coyotes and evocative bugles of sandhill cranes, the occasional marsh wren sounding off, winnowing Wilson’s snipe, the deep and liquid call of American bitterns, Virginia rails and soras (yellow rail brethren). A summer night can be busy and loud. But in the right places, the tic-tic, tic-tic-tic carries through the din, a good half-mile or more under the right circumstances.

The results of our data collection of more than two decades suggest that yellow rail numbers are declining. There could be several factors at play, but loss of breeding habitat due to drought and groundwater pumping is likely a major contributor. Potential threats from development, energy extraction, and climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change make this species a bird of conservation concern across Canada and the United States.

The good news? There might be a better way to count these birds. Miles Scheuering, a master’s student at Oregon State University, is experimenting with Automatic Recording Units as a method of determining yellow rail presence and density. Automatic Recording Units are small devices that collect sounds from the surrounding environment and store them to be reviewed and analyzed later. They are being used around the world to help people determine the presence and abundance of many kinds of calling animals. It is possible to train a computer program to recognize and count specific types of sounds during analyses, including the tic-tic-tic of a yellow rail. Automatic Recording Units could really change how we track populations of yellow rails in the future or detect them in remote locations where it’s difficult for humans to conduct censuses.

The other big question the working group is tackling is to discover where western yellow rails spend the winter. How can we fully conserve this population without knowing where it spends the winter and where it might stop over during migration? Incidental sightings over the years point to salt and brackish marshes in coastal California, mostly from the Bay Area but a few records as far south as San Diego. There are even a few records inland from the Los Banos area (mid-San Joaquin Valley) of California from the very early 1900s. We are currently considering various radio-frequency telemetry devices (such as Motus or satellite telemetry) to help answer this fundamental question, but we are moving cautiously before attaching transmitters to individuals of this very small population of birds.

Yellow Rail Bugle Calls

Recently, Dr. Chris Butler, an associate professor at Texas A&M University, and students from his lab recorded a novel sound that yellow rails make during the winter: the bugle call. Working in coastal Texas where midwestern yellow rails winter, Butler recorded, played back, and caught on video yellow rails making this odd call that vaguely resembles the distant bugling of sandhill cranes. This caught the yellow rail world by great surprise. Many reputable yellow rail researchers across the U.S. and Canada had never heard this call before, including the seasoned members in our working group. This summer we experimented a bit with this call, playing this call back to tic-tic-tic-ing males on territory and boy did they respond! They came running out of their sedgy hideaways to confront the intruder!

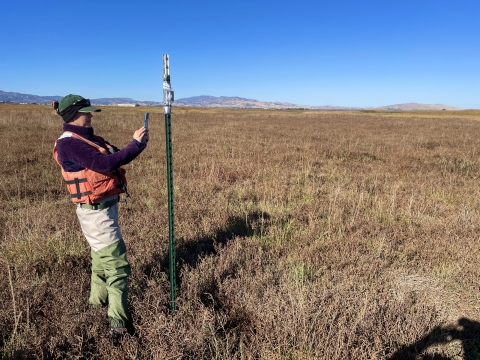

But yellow rails may only use the bugle call in the winter. Laurie Hall, an ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, is currently exploring this possibility by deploying Automatic Recording Units in likely wintering locations around the San Francisco Bay-area marshes, and by incorporating this bugle call playback into existing call-playback surveys of Ridgeway’s and black rails this winter.

In early January, Laurie struck gold! After many hours in the field, she managed to elicit a bugle response from a bird in a marsh in the north bay delta region near Fairfield, California. With Automatic Recording Units deployed, and more call-playback work, we might soon have a much clearer idea of where yellow rails spend the winter in the west.

There is so much we want to learn to help conserve yellow rails: Is there a post-breeding dispersal event before their fall migration as many other birds have? What is the timing of their molt? What habitat type are they seeking in the fall and winter? Are there particular places we could protect to help them as they migrate and rest through the winter? Will feather samples reveal genetic separation between eastern and western yellow rails? Can eDNA help us find where yellow rails are in both summer and winter? This is a short list of some of our most pressing questions.

In the meantime, making sure breeding habitat at Klamath Marsh National Wildlife Refuge can withstand the consequences of climate change and greater demand for water in the West will be a primary focus of this group. At least two other sensitive species depend on these same permanent shallow wetlands, the Miller Lake lamprey and Oregon spotted frog.

If nothing else, we at least can work to make sure the refuge — the single most important place for breeding western yellow rails — remains secure well into the future for the small, secretive denizens of the marsh.