When you step foot on a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) National Wildlife Refuge, it can be a special experience. You might hear the howling wind and rushing waters or see birds soaring in the sky, wildlife running through trees or scampering across a meadow, fish jumping in the rivers, and a vibrant exhibit of wildflowers.

The land providing this remarkable experience is the mother to the First Peoples we know today as Native Americans and is filled with vital and essential resources that they tenderly nurtured, respected, and protected. Native Americans are the historical stewards of many public lands, and we honor their efforts by continuing the conservation legacy they started.

In partnership with the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and the Fort Peck Tribes, new signs have been installed at Ninepipe, Pablo, and Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuges in Montana that reflect the languages of the first people who roamed the Americas.

Honoring Our Past

At the Ninepipe and Pablo Refuges, visitors will find multilingual signs featuring the Séliš (Salish), Ql̓ispé (also known as Pend d’Oreille or Kalispel), Ksanka (also known as Kootenai) and English languages. These signs bear the names of the refuges in each language, as well as an English translation of the name’s meaning. For example, the Séliš-Ql̓ispé name for Pablo National Wildlife Refuge translates to “Trees-Tapering-to-a-Point Human-made Lake.” The new signs also bear the logo of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes to acknowledge that the refuges are on land owned by the Tribes.

“We are pleased to see the Service include our Indigenous names for these refuges, as well as recognition that the refuges are located on Tribally owned trust land and were originally created at the request of the Tribes,” said former Chairman Ronald Trahan of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. “Many people do not know this history, so the signs will serve important educational purposes.”

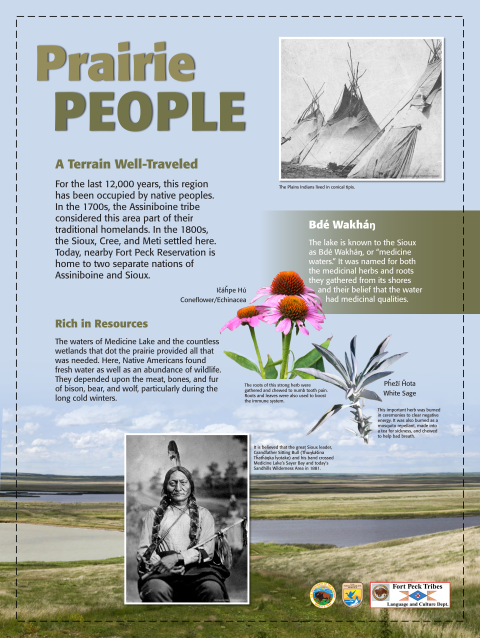

At Medicine Lake Refuge, a bilingual informational sign developed with the help of the Fort Peck Tribes Language and Culture Department will soon be installed at the refuge. This sign provides historical and cultural information about the land, including the names of prominent plants and landmarks in the Dakota language. The name Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge is not random, either — it is a reflection of the name given by the Sioux, who call the lake Bdé Wakháŋ, or “medicine waters.” It was named for both the medicinal herbs and roots they gathered from its shores and their belief that the water had medicinal qualities.

The signs reflect ongoing efforts by Native communities to preserve and revive the use of Indigenous languages, an integral part of their cultural identity. The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes are working to keep languages alive for future generations by making them a part of daily life. On the Flathead Indian Reservation, it is increasingly common to see Indigenous place names on point-of-interest signs along U.S. Route 93, the main thoroughfare connecting towns in the area.

“This is an important step toward strengthening our invaluable partnership with the Tribes by being more inclusive,” said Amy Coffman, Station Manager for the Northwest Montana Wetland Management District. “The Service wants to do a better job of recognizing the role of the Tribes, supporting their cultural priorities, and recognizing our common history.”

History of Ninepipe & Pablo National Wildlife Refuges

More than a century ago, the Tribes began to campaign for the federal government to designate the Ninepipe and Pablo reservoir areas within the Flathead Indian Reservation as refuges for game and bird conservation. After multiple requests from the Tribes, President Harding issued two Executive Orders in 1921, establishing Ninepipe and Pablo National Wildlife Refuges. In 1948, FWS secured a perpetual easement from the Tribes to use the lands as National Wildlife Refuges.

History of Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge

For the last 12,000 years, Eastern Montana and Western North Dakota have been home to Native peoples. In the 1700s, the Assiniboine Tribe considered the land comprising the Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge and the surrounding area part of their traditional homelands. In the 1800s, the Sioux, Cree and Meti settled there. Today, nearby Fort Peck Reservation is home to two separate nations of Assiniboine and Sioux. Tribes historically used this area while hunting big game herds and waterfowl, so many of the surrounding hills contain stone rings indicating locations of ancient campsites.

The Medicine Lake Refuge was established in 1935, in an area once covered by glaciers which formed the rolling plains of northeastern Montana, between the Missouri River and the Canadian border. In 1980, the Medicine Lake Site was designated as a National Natural Landmark by the National Park Service.

Written by Melissa Castiano, Christina Stone, Mikaela Oles and Jessica Sutt, in collaboration with Amy Coffman and the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes