“We live in an age of rising seas. Now in our own lifetime we are witnessing a startling alteration of climate.”

Old news? Yes, but older than you think. Rachel Carson wrote this to a friend nearly 75 years ago, long before there was consensus on climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

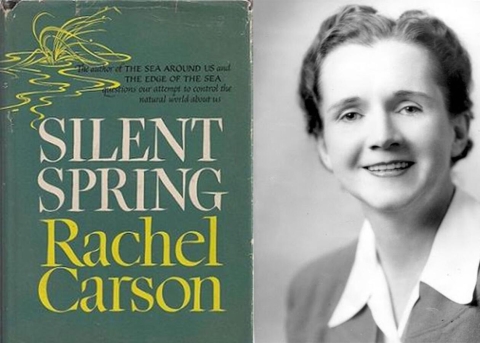

Learn more about climate change , and even prior to “Silent Spring,” her seminal work about the dangers of pesticides that captured the public’s attention and sparked the environmental movement.

Carson, who worked for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for nearly a decade, hoped to write a book about rising sea levels and warming ocean temperatures, but she died of cancer before that was possible. Had she lived to tell the story of large-scale climate change in the same relatable manner she wrote about deadly chemicals, would people have listened and acted sooner?

Onto something

Though best-known for “Silent Spring,” Carson was already a popular writer when it published in 1962. Her earlier trilogy about the world’s oceans captured readers’ imaginations and opened their eyes to a world they'd never seen. It also broached the subject of a changing climate.

The trilogy’s second installment, 1951’s “The Sea Around Us,” won both the National Book Award for Nonfiction and the John Burroughs Medal in nature writing. It was on “The New York Times” Best Sellers List for 81 weeks and translated into 32 languages.

In the book, Carson writes, “For the globe as a whole, the ocean is the great regulator, the great stabilizer of temperatures.” She describes a close connection between climate and circulating ocean currents. One of those currents, the Gulf Stream, carries warm water from the Gulf of Mexico up the U.S. East Coast; across the North Atlantic to Greenland, Iceland, and Scandinavia; and down the European coast to the Bay of Biscay, giving Europe a more temperate climate than places at similar latitudes.

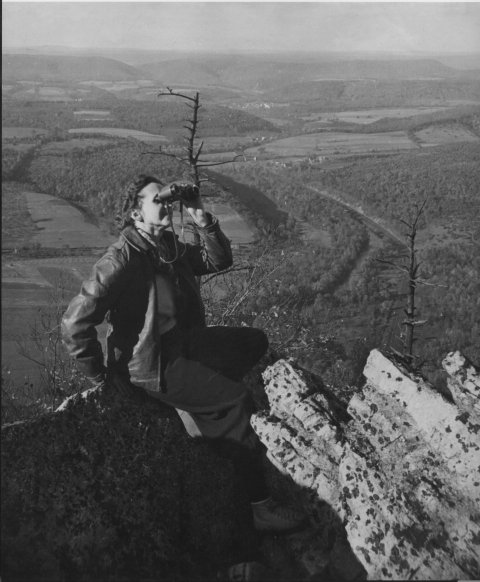

Carson notes that oceanographers in the 1940s discovered significant changes in the temperature and distribution of North Atlantic currents, including the Gulf Stream. She connects these changes to a warming trend in the Arctic that began about 1900 and became significant by 1930. By mid-century, when she was writing, the climate in subarctic and temperate regions was also moderating. “The frigid top of the world is very clearly warming up,” she says.

She provides numerous examples as proof: Shipping seasons in the North Atlantic and Arctic Sea are lengthening due to reduced sea ice. New bird species are seen in the far north. Atlantic cod, rarely found along the coast of Greenland at the turn of the century, are abundant there and spotted 300 miles farther north. Iceland and Norway have longer growing seasons. And glaciers are melting.

In the third volume of the trilogy, 1955’s “The Edge of the Sea,” Carson looks a bit closer to shore. She writes that Cape Cod, the East Coast’s long-accepted boundary between warm-water species and those that thrive in colder waters, is no longer the dividing line it once was. As a result of warming ocean temperatures, more-southern species had begun to move north in the early part of the century. Among them was the green crab, which was devastating the Maine clamming industry as she wrote.

While Carson recognized climatic changes and their effects, she didn’t link them to human activity. Beyond continued warming following the last ice age, scientists at the time pointed to two possible causes of changing climates: cycles of oceanic tides that recur every 18 centuries and an increase in solar activity. Researchers had been studying greenhouse gases, but it wasn’t until the 1960s, as the environmental movement sparked by "Silent Spring” took off, that they began to link global climate change to human activity.

Out of time but on the mark

Carson’s writing was eerily prescient. Today, human-caused climate change is an established fact. Sea levels and temperatures are rising at an alarming rate. The Gulf Stream is warming and slowing down, and scientists are concerned about the effects on Europe’s climate.

Though science hadn’t yet caught up with the planet’s symptoms, Carson knew what was happening was significant, and she wanted to share it with the world as only she could. Given more time and research, perhaps she would have alerted us all to the causes and dangerous effects of climate change, as she had the perils of pesticides.

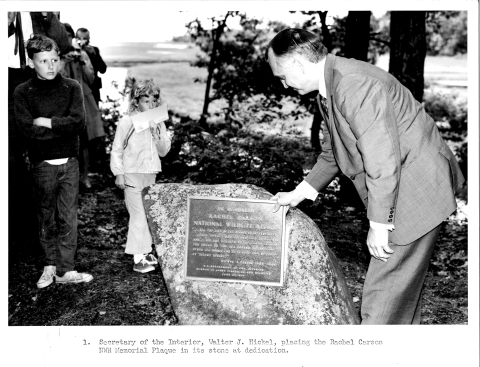

Her contributions to environmental conservation are honored in perpetuity at Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge on Maine’s southern coast, where the writer spent much of her life. Service staff there are working with partners to protect inland areas where salt marshes can migrate as the rising seas Carson wrote about 75 years ago threaten them more each day.

In a television interview a few months after the release of "Silent Spring,” Carson, wearing a wig to hide hair loss caused by her cancer treatment, observed: “I think we’re challenged, as mankind has never been challenged before, to prove our maturity, and our mastery, not of nature, but of ourselves.”

Her words are as apt today as they were more than 60 years ago.