For two days, Qikiqtaġruk’s (Kotzebue’s) 2021 “summer of no summer” held true to its name – a canopy of clouds idled low atop the peninsula, heavy with rain, many gray sweeping gales disappearing all sunshine and views of Brooks Range peaks.

On land, a feeling of unease lingered amongst Sara Owen and her field partner and pilot as they waited, the hours passing slowly, in a cozy Selawik National Wildlife Refuge apartment. With their flight grounded, a rare opportunity to collect aerial imagery of the North Slope’s magnificent wetlands seemed to be slipping through their fingers.

But in hindsight, says Owen, a wetlands coordinator for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Regions 6 and 8, the precipitation was a blessing. When skies finally cleared and their helicopter lifted – crossing two miles of water separating the Hotham Inlet from the Chukchi Sea, then flying over tundra polygons and magnificent mountaintops – the views from her window seat rivaled any other she had experienced over her 20 years of photographing wetlands across America.

Northern Alaska’s riparian riparian

Definition of riparian habitat or riparian areas.

Learn more about riparian ecosystems – the Kobuk, the Noatak, the Selawik and their tributaries – pulsed magnificent azures, rushing and rejuvenated from the week’s five inches of rain. “With a bird’s eye view, you could even see riparian vegetation, associated linking wetlands, and side channels snaking through trees,” she recalls.

In the air, as Owen had done tens of thousands of times before, she captured not only images of alpine and sea-level marshes, but also their precise latitudes, longitudes, and orientations -- each image’s north-, south-, east-, and west-facing directions.

This practice, known as geotagging, Owen says, is becoming increasingly important for scientists in Alaska.

What Are Geotags?

If you’ve ever snapped a photo with a smartphone and an internet connection, odds are you’ve practiced geotagging: Capturing an image and the approximate location (the “geotag”) of where that photo was taken.

To most people, this data may be unimportant. But for scientists working throughout Alaska’s lands and waters – many of which haven’t been studied closely with Western methods, or change drastically depending on precipitation or season – knowing the precise location of an image can make its contents even more meaningful.

“These photos are quickly becoming interdisciplinary tools for scientists studying a variety of subjects,” says Sydney Thielke, Alaska’s wetlands coordinator. “The value of the geotagged photo is truly in the eye of the beholder.”

As a wetlands biologist, Thielke says that she pays the most attention to vegetation, soils, and hydrology within a photo. “But when the fire ecologist is looking at the photos, she is looking at different clues, like burn severity and depth,” she says. “The refuge botanist will zoom in and identify much more detail about the species present.”

Knowing the exact location of such a landscape saves scientists time and expenses, and often fosters interconnected discussions amongst those with different specialties. Multiplied across Alaska’s many landscapes, the practice of geotagging photos, which is becoming more common, continues to have a positive impact in myriad communities.

Mapping Alaska’s Wetlands

Wetlands are some of America’s most important habitats – they protect coastlines, store carbon, support biodiverse life, and keep waters clean and healthy.

Because of the crucial role that wetlands play, the National Wetlands Inventory (NWI) has guided science-based decision-making by collecting up-to-date and detailed information about these lands for decades. Policymakers, researchers, engineers, and many others depend on NWI’s hydrology, soil, and vegetation analyses when considering studies, protections, and development.

“There’s so many wetlands in Alaska, you can’t build a road and not hit one," says Owen, sharing one example of how NWI intersects with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).

Today, NWI's work is most robustly illustrated with their online Wetlands Mapper, a publicly available tool that displays data-rich maps of America’s wetlands, much of it as a result of geotagging.

But the map is still a work in progress, and nowhere is the effort to complete it more important, or challenging, than in Alaska. About 43 percent of the state is wetlands, comprising 63 percent of the country’s total.

Today, only about 40 percent of Alaska’s wetlands are fully mapped. Though, under Thielke’s direction, another 40 percent is currently being completed.

These new maps, Owen says, will inform crucial understandings of regions where weather is becoming increasingly unpredictable – coastal areas afflicted by storm surges, land regression, and sea level rise; areas where permafrost is thawing; monitoring water levels and capacity amongst Arctic lakes; and how warmer temperatures are affecting snowpack and snow melt.

“Data shows that the Arctic is warming a lot faster than the rest of the world,” Owen says. “There's a lot of potential research that may result once we have these wetlands mapped, being able to track changes through time.”

‘Ground-Truthing' Island Vegetation

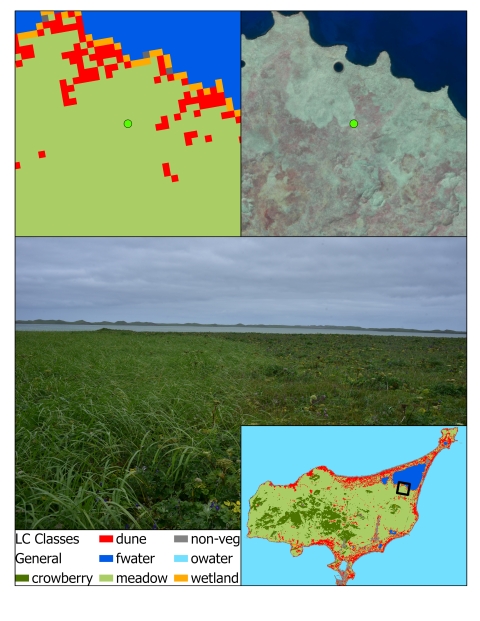

Last summer, while walking through the rich meadows of St. Paul Island, the vast extent of plants growing before Hunter Gravley suddenly split into two drastically different shades of green.

“I was standing there, a dune grass meadow on the left, and an herbaceous meadow on the right,” he recalls.

The rich color divide spreading for more than 100 meters gave Gravley – a refuge botanist and GIS (geographic information systems) enthusiast – an opportunity to hone his skills as a twenty-first century cartographer.

Capturing several GPS-synced photos, he linked the different species of plants to their specific locations on the island. These records showed how vegetation across St. Paul had changed over time. When he returned from the field, they were used to "ground-truth" a new land cover map that was in production at the time.

Geotagging also came in handy for Gravley last September, when he joined Anchorage Field Office scientists on a visit to Adak Island in the hopes of finding populations of the endangered Aleutian Shield Fern.

Not only did the team locate all four known populations – completing the first official count in more than two decades – but the geotagged images allowed them to later plot the ferns’ precise locations in a three-dimensional, digital elevation model.

“When I first started out as a biologist, I didn’t geotag photos,” Gravley says. “I just took the pictures, put them in a folder, and tried to keep track of location. I thought these [recent trips] were successes, the technology working to our advantage.”

Subsistence and Co-Stewardship

Since time immemorial, marine mammals have been a cornerstone of Unangax̂ culture on the Pribilof Islands, an ecologically and socially rich archipelago currently within the Bering Sea unit of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge.

Today, hundreds of Alaska Natives on St. Paul and St. George islands – two of the Pribilof’s four islands – continue to depend upon laaqudan, northern fur seal, and qawan, Steller’s sea lion, for subsistence living; physical, emotional, and spiritual health; and to continue practicing traditional ways of life.

But these and other marine mammal species have long been in decline. In 1988, the Marine Mammal Protection Act listed laaqudan as “depleted.” Over the past 60 years, qawan pup production on Walrus Island has declined by over 98%, from 2,866 pups born in 1960 to only 48 pups born in 2015.

The weakening health of these keystone species, in 2004, sparked local action. The St. Paul and St. George communities, along with volunteers, scientists, and agency partners, began to develop community-based monitoring programs to collect “reliable local ecological data” about marine mammals that would inform official decisions – including those related to harvesting and protections.

That initial effort has since grown into what is now known as the Indigenous Sentinels Network (ISN), which today “supports the collection of Indigenous, local, and traditional knowledge and scientific information to empower holistic, ecosystem- and community-centered management and decision making,” says Hannah Marie Garcia, the Network’s coordinator for the Aleut Community of St. Paul Island.

By providing rural and Indigenous communities with technologies and tools to collect data and geotag photos, she says, ISN continues to help local and Alaska Native communities be heard when decisions are made about subsistence harvests or species management.

“We are ensuring that there’s another path for community and local knowledge to start filtering into what’s typically seen as traditional western research,” Garcia says.

One current ISN project is their Skipper Science Partnership’s Black Cod Stomach Contents Program. Everyday fishers in the eastern Gulf of Alaska can download an app and upload fish measurements and geotagged photographs of black cod stomach contents, smeared on a bucket lid. The data is helping scientists at the Alaska Fisheries Science Center Resource Ecology and Fisheries Management Lab better understand food web shifts and feeding habits in the region.

“Stemming from the history that fishermen often felt dismissed in public comment periods, or that their observations on the water are seen as anecdotal or one-off, we can empower them through a tool that crowdsources data and their local observations in a rigorous and standardized way,” says Robson, ISN's technical director.

With a grant from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, ISN is also supporting the Fish Map App, which empowers community resource users and agency researchers to use geotagging to expand Alaska's Anadromous Waters Catalog – and receive compensation for their help.

Other ISN programs and efforts include tracking subsistence harvests, furthering invasive species invasive species

An invasive species is any plant or animal that has spread or been introduced into a new area where they are, or could, cause harm to the environment, economy, or human, animal, or plant health. Their unwelcome presence can destroy ecosystems and cost millions of dollars.

Learn more about invasive species prevention, helping agency surveys, and collecting near-shore temperature measurements – all while ensuring these communities maintain complete data sovereignty.

“I’m really excited about seeing these programs support community sentinels in collecting local knowledge that can help drive research and policy changes,” Robson says.